New Food Economy: North Carolina’s hog and poultry farmers are directly in the path of Hurricane Florence. Are they ready?

by H. Claire Brown | September 11th, 2018

Previous storms prompted manure-related environmental disasters. This week, North Carolina could get very smelly.

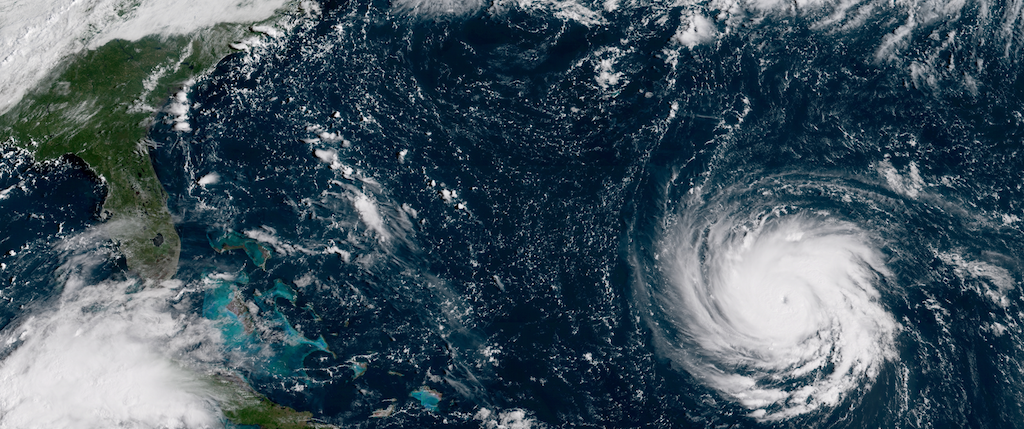

As of Tuesday afternoon, more than a million people are under mandatory evacuation orders in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina as Hurricane Florence draws closer to the coast. Meteorologists are predicting that the Carolina coasts will start seeing tropical storm-force winds late Wednesday night, with hurricane-force winds arriving at around noon on Thursday and official landfall likely on Thursday night. North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper declared a state of emergency on Friday.

The governor also lifted restrictions on weight-limited vehicles like semi-trucks so that farmers could harvest crops ahead of the storm. Heather Overton, assistant director of public affairs at the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services, says the agency sent 12 regional agronomists to survey farmers around the state. They estimate about two-thirds of the state’s tobacco and three-quarters of the corn have already been harvested, but sweet potato and peanut harvests are just getting underway.

“Farmers are working to get as much out of the fields as they can,” Overton says. “We urge them and everybody else to take the situation seriously.”

Meanwhile, the state’s pork and poultry farmers are stocking up on feed and fuel and moving animals to higher ground. “Some of the farms will have sent their birds to the processing plant a little early to move them off the farm,” says Bob Ford, executive director of the North Carolina Poultry Federation. “We’re in pretty good shape,” he adds. The pork industry seems similarly nonchalant: Andy Curliss, the North Carolina Pork Council CEO told Bloomberg he’d only be concerned if the state got more than 25 inches of rain.

Meanwhile, the state’s pork and poultry farmers are stocking up on feed and fuel and moving animals to higher ground. “Some of the farms will have sent their birds to the processing plant a little early to move them off the farm,” says Bob Ford, executive director of the North Carolina Poultry Federation. “We’re in pretty good shape,” he adds. The pork industry seems similarly nonchalant: Andy Curliss, the North Carolina Pork Council CEO told Bloomberg he’d only be concerned if the state got more than 25 inches of rain.

In reality, hog and poultry farmers have more to worry about than flooded barns. Animal agriculture produces about 10 billion pounds of wet waste a year in North Carolina, and a lot of that waste is stored in open lagoons. During Hurricane Floyd in 1999, those lagoons broke open and dumped waste into public waters, an environmental catastrophe that was later blamed for algal blooms and fish kills. During Hurricane Matthew in 2016, 14 lagoons flooded and millions of animals died. Yet in a blog post admonishing readers to “beware of misleading narratives and check facts,” the North Carolina Pork Council argued that the vast majority of lagoons operated as advertised during Matthew, which minimized the damage.

Overton says North Carolina hog farmers have begun spraying manure onto fields to free up space in the lagoons should major rainfall accompany Florence. Transferring waste from the pit to the field helps minimize the risk of a flooded lagoon, but the state’s Department of Environmental Quality regulates the amount of manure farmers are allowed to apply. Overton says that farmers have had several days to prepare, but restrictions on applying manure have not been lifted despite the pending storm. “From what we understand, they are in pretty good shape.”

Farmers are required to stop applying manure at a certain point after weather watches and warnings are issued by the National Weather Service—typically hours before the severe weather begins. This can put them in a double-bind: leave the manure in the lagoons and risk a breach caused by flooding, or break the law by applying it on the farm too late and risk letting it run off into the public water supply when the storm comes. There’s a powerful incentive to break the rules.

Farmers are required to stop applying manure at a certain point after weather watches and warnings are issued by the National Weather Service—typically hours before the severe weather begins. This can put them in a double-bind: leave the manure in the lagoons and risk a breach caused by flooding, or break the law by applying it on the farm too late and risk letting it run off into the public water supply when the storm comes. There’s a powerful incentive to break the rules.

“We have consistently, in advance of similar storms even of lesser intensity, witnessed illegal spraying after that prohibition is triggered,” says Will Hendrick, staff attorney for the Waterkeeper Alliance, an environmental advocacy group. “That’s part of what we will be on the lookout for during our pre-storm monitoring.”

Hendrick’s team will also be monitoring agricultural flooding from the air so that it can alert state agencies to mobilize a response. He points out that the state of North Carolina doesn’t always know where poultry farms are located—they’re not required to apply for a permit.

“I don’t think anyone is as optimistic as to assume that there won’t be considerable damage in North Carolina,” Hendrick says. “We’re going to do our best to determine it, assess it—and in particular, the damage that’s caused by threats to water quality.”