New Food Economy: Kansas farmers are running out of water. Can they pull off an environmental miracle in Charles Koch’s home state?

Images: U.S. Geological Survey, Kansas Farmers Union (Flickr), Fortune Brainstorm (Flickr); graphic by TNFE

by Corie Brown | December 20th, 2018

Kansas producers say policy solutions aren’t necessary to save the Ogallala Aquifer, the state’s most economically important natural resource. That’s up for debate—but a Koch think tank may make regulation impossible anyway.

For the past year, I’ve traveled across Kansas, a journey that’s entailed half a dozen visits and thousands of miles on the odometer of my mother’s worn-out sedan. A fourth-generation daughter of the plains, I was sobered by the state’s profound and seemingly irreversible depopulation, a depressing downward trend driven by its dependence on heavily mechanized commodity agriculture. It’s a phenomenon I wrote about for The New Food Economy in April of this year.

It was a difficult piece to write. I was disturbed by what I encountered in my home state—towns I knew from childhood emptying out, struggling farmers leaving their land to work elsewhere. And while I received many sorrowful letters from Kansans past and present, writing to say they recognized my depiction, others sent responses of a more hopeful variety. It’s not all bad news in Kansas, these letters insisted. I wanted to see if there was truth to that, if one day Kansans might reverse the state’s linked downward spirals of depopulation and agricultural overproduction.

When I returned this fall to sit down with farmers, ranchers, dairymen and other rural Kansas leaders I asked what, if anything, is being done to stabilize the state. Rather than talk solutions, however, a different theme quickly emerged: In conversation after conversation, the depletion of the Ogallala Aquifer was top of mind. Kansas’s most important natural resource is running dry, imperiling the state’s economy and the approach to farming that helps drive it.

When I returned this fall to sit down with farmers, ranchers, dairymen and other rural Kansas leaders I asked what, if anything, is being done to stabilize the state. Rather than talk solutions, however, a different theme quickly emerged: In conversation after conversation, the depletion of the Ogallala Aquifer was top of mind. Kansas’s most important natural resource is running dry, imperiling the state’s economy and the approach to farming that helps drive it.

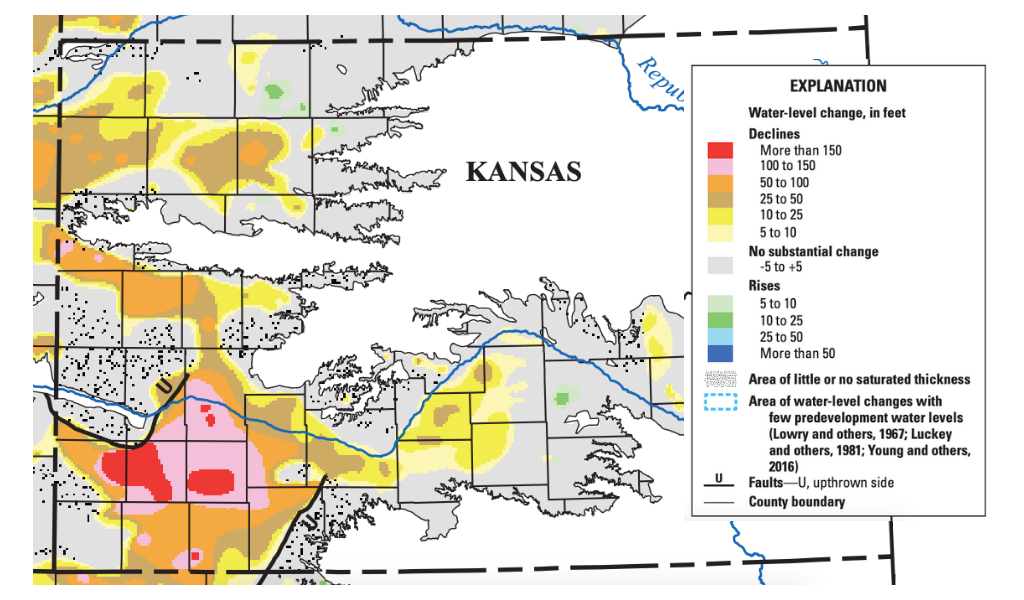

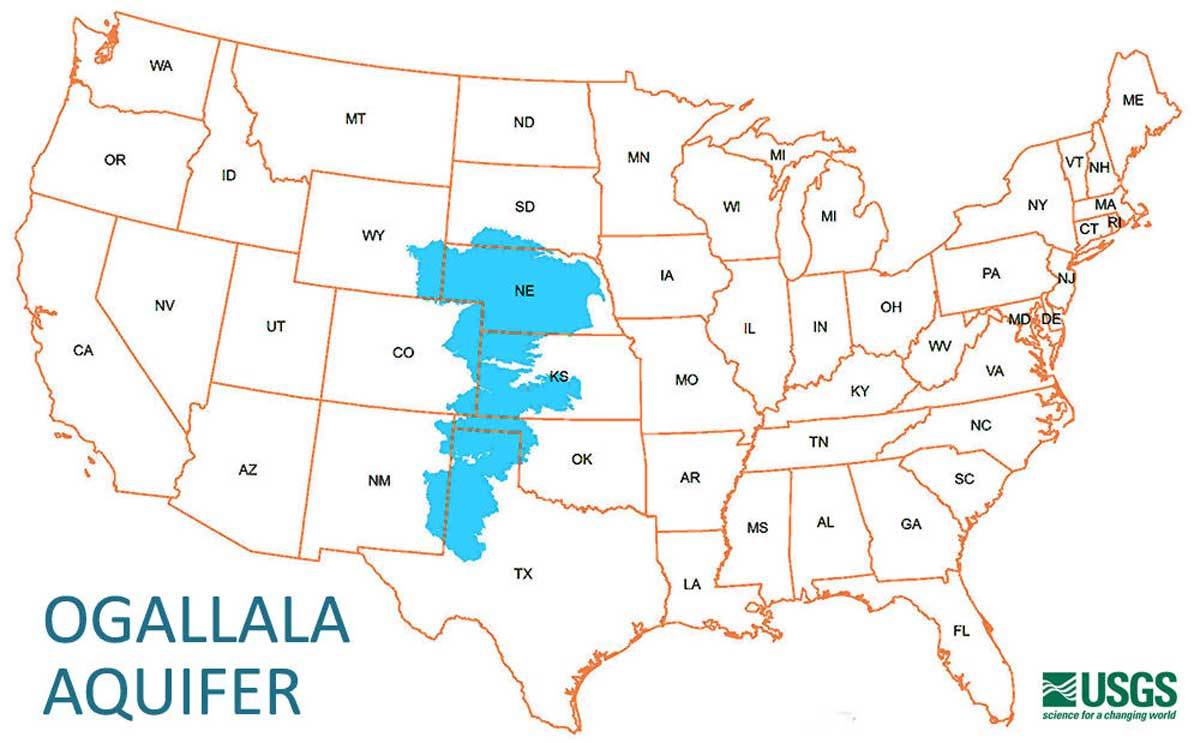

The Ogallala Aquifer is a massive, subterranean formation of semipermeable rock that spreads out under eight states, from Wyoming to Texas and New Mexico. Water pumped up from that thousands-year-old, waterlogged, sand-and-gravel sponge turned the western third of the state from a Dust Bowl disaster into an agricultural promised land. A report from the Kansas Department of Agriculture calls the Ogallala the “the largest, most economically important ground water source in Kansas,” and the primary source of water for all uses in the western portion of the state. The problem is, water is being used much faster than the Ogallala can replenish itself.

A 2013 study published by The National Academy of Sciences found that the Ogallala has already been drained of 30 percent of its water. Citing that study, among others, the nonprofit Kansas Leadership Center issued a report: “Running out of water. Running out of time.” It described an “irreversible depletion” of the Ogallala’s reserves. While the report’s list of the 150 largest users of Ogallala water users includes some municipalities, it is dominated by agricultural and food processing users, which means that, while western Kansas farmers are largely to blame for the Ogallala’s decline, they also are the most at risk from its demise.

U.S. Geological Survey

The Ogallala Aquifer’s water reserves are declining. While Kansas farmers are largely to blame, they also are the most at risk

“At current rates, the Ogallala will essentially be unusable by farmers, both in terms of quantity and quality, within this generation,” says Patricia Clark, community relations manager at Kansas Leadership Center and the Kansas director of USDA Rural Development during the Obama Administration.

Kansas agriculture, then, faces an existential choice: It can cut back water use voluntarily now and face a decline in farm productivity, or it can continue to ignore the problem and face far more dire consequences as the water runs out.

With a problem so serious, I expected to find state environmental groups fighting for strict conservation measures, and legislators proposing new laws limiting water use. But there is none of that. The state government is MIA. There are no rules or regulations, no reliable leadership. Thanks to the steep business tax cuts made in 2012 under the state’s former Republican Governor, Sam Brownback, which are widely recognized as having been catastrophic and were largely repealed this year, the state is in crisis management mode, with little ability to enact bold reforms. There is nothing in place that would compel the state’s farmers—legally, or by any other means—to use the aquifer’s reserves more sustainably.

The fate of the Ogallala, as things currently stand, rests completely on voluntary efforts—the foresight, self-restraint, and altruism of the people of Kansas.

The rural Kansans I talked with say they care too much about the future of their land to fail to protect the Ogallala. The vitality of their soils is precious to them. These farmers assure me that Kansas will come to embrace sustainable agricultural practices like no-till farming, cover crops, and other conservation measures, completely transforming their relationship to the land over the next few decades. They’ll have to, the logic goes, because the stakes are too high and the fallout so potentially cataclysmic.

The rural Kansans I talked with say they care too much about the future of their land to fail to protect the Ogallala. The vitality of their soils is precious to them. These farmers assure me that Kansas will come to embrace sustainable agricultural practices like no-till farming, cover crops, and other conservation measures, completely transforming their relationship to the land over the next few decades. They’ll have to, the logic goes, because the stakes are too high and the fallout so potentially cataclysmic.

But is that realistic? Can people truly be counted on to be voluntary environmentalists, and preserve a critical public resource for future generations, in the complete absence of regulation? Will Kansas farmers act against their short-term economic self-interest? Finding out required talking to dozens of people, making a visit to Ted Turner’s bison ranch, and tracking the impact of the state’s most influential billionaire: Charles Koch.

“People with no stake in the outcome of farming want to make the rules,” says Lon Frahm, whose family owns 22,000 acres, and who farms a total of 34,000 acres by Colby, near the state’s northwest corner. “Anyone who wants to change the rules ought first to come out here to live.”

We spoke at City Limits Bar & Grill located just off I-70, the east/west transportation corridor connecting Kansas City with Denver, Colorado. The new nostalgia-themed space is part of a thriving fast-food and motel hub serving interstate truckers and travelers. In Frahm’s view, extraordinary technological gains will make environmentally sustainable agriculture not just possible in Kansas, but the norm. He points out that new techniques on the horizon could allow farmers to cut chemical use to 1 percent of what’s typical today. That attitude is common among the state’s producers. They can be trusted to do what’s best for the land, they believe, because that’s going to be the most sensible and economically efficient way to operate.

Environmentalists in Kansas have to be pragmatists, says Rob Manes, Kansas director of the Nature Conservancy. “Kansas hasn’t been very good at conservation and environmental activism.” A year ago, he says, he stopped believing progress was possible. But lately, he’s regained a measure of optimism. “The more successful farmers and ranchers are talking about soil health. They are knowledgeable about the environment.” And, instead of talking about productivity, they have started talking about profitability, he says, a critical shift in thinking to curb the overuse of expensive chemicals.

Still, Manes acknowledges that progress comes only voluntarily here. “If what we do isn’t commensurate with what everyone wants, it will be undone in Kansas,” he says. “Environmental protection must exist within the culture and commerce of farming.”

The theory that private landowners will lead the state’s conservation efforts is being put to the test with the crisis facing the Ogallala.

Kansas has a priority system—first in time, first in line—that rewards the state’s earliest farmers with unrestricted access to water. In practice, with the seemingly limitless Ogallala water, farmers have pumped as much as they want throughout the years. And why not? There are no regulations in place to prevent them from doing so.

Barry Frantz is the coordinator for the USDA Ogallala Aquifer Initiative, a federal program to help states address the depletion crisis. Water is a state issue, so all he can do is suggest conservation options. Nebraska, for instance, has instituted maximum water withdrawals for its farmers. Colorado is offering to buy back water rights, a way to pay farmers to dry farm. But Kansas hasn’t tried anything as sweeping, or as binding. “Kansas farmers are interested in conservation,” Frantz says, but no one is holding their feet to the fire. They are trying a “smattering” of small initiatives. But those may not be enough.

Barry Frantz is the coordinator for the USDA Ogallala Aquifer Initiative, a federal program to help states address the depletion crisis. Water is a state issue, so all he can do is suggest conservation options. Nebraska, for instance, has instituted maximum water withdrawals for its farmers. Colorado is offering to buy back water rights, a way to pay farmers to dry farm. But Kansas hasn’t tried anything as sweeping, or as binding. “Kansas farmers are interested in conservation,” Frantz says, but no one is holding their feet to the fire. They are trying a “smattering” of small initiatives. But those may not be enough.

If Kansas can’t or won’t do more, the aquifer will recede beyond the reach of its wells and the state’s farmers won’t be able to farm their land, says Frantz. Shifting to cattle grazing is so much less profitable, he says, “People will have to leave their land.” The environmental concern becomes what happens to that abandoned land. It won’t revert to the beautiful prairie it once was unless it is managed properly. It might not be Dust Bowl II, but the land will degrade beyond recognition.

In some spots in western Kansas, that point of no return is only five to 10 years away, says Kansas Leadership Center’s Clark. As the aquifer recedes, levels of arsenic and other toxins become concentrated and dangerous. Cleaning the water is far beyond the budgets of rural water districts in depopulated areas.

U.S. Geological Survey

As the aquifer recedes, levels of arsenic and other toxins become concentrated and dangerous

“Kansans tend to not take action until we are at the cliff’s edge. And it may already be too late when it comes to water,” says Clark. “What frustrates, worries, and concerns me is that we can’t have these conversations in Kansas. Everyone shuts down. It’s Germanic. We turn our heads away rather than leaning into a problem.”

It would be easy to blame the current situation on the hands-off, “don’t tread on me” attitude toward government intervention that is so common in the state. But the fact is that Kansas’s dilemma is more than cultural. It’s the result of a strategy that has been aided and abetted by proponents of radical free-market capitalism, a philosophy pushed hard by the state’s wealthiest resident: Charles Koch, CEO of Koch Industries.

In the absence of government leadership in rural Kansas, Wichita-based Koch is offering help that falls in line with his well-trod anti-government political philosophy. The Kansas Policy Institute (KPI) is an influential free-market think tank founded and largely funded by Koch, though it does not advertise the connection.

When I noted Koch’s financial support for KPI, its president, Dave Trabert, created a bit of a kerfuffle. “With due respect, that’s a false assumption,” he said. I pointed out that KPI’s board includes former Koch employees and Charles Koch’s closest local friends. I’ve spoken with numerous people in the state who point to KPI as Koch’s local policy platform, including folks who support it financially.

A young KPI staffer taking notes snapped that I was “accusing” the institute of being associated with Koch. I asked, “What’s so wrong with being associated with Charlie Koch?” After a few beats of silence, Trabert acknowledged Koch is a main funder, and the interview continued.

A young KPI staffer taking notes snapped that I was “accusing” the institute of being associated with Koch. I asked, “What’s so wrong with being associated with Charlie Koch?” After a few beats of silence, Trabert acknowledged Koch is a main funder, and the interview continued.

KPI has announced the creation of the Sandlian Center for Entrepreneurial Government to help rural Kansas towns and counties “rationalize” their public payrolls. Public services, such as education, are often best provided by non-government entities, according to the KPI mantra. Free of charge, KPI’s Sandlian Center will send teams of accountants, government specialists, and tax experts to communities interested in cutting costs. The end goal, said Trabert, is to cut taxes, which KPI believes will attract new businesses to the job-starved region.

A champion of Brownback’s now-infamous Kansas business tax cuts that drained an estimated $1 billion a year from state coffers, Trabert insisted the problem with those tax cuts was the governor’s failure to cut spending too, specifically spending on public education. He thinks this new approach—cut spending before you cut taxes—will be more successful.

Public employees make up 26 percent of Kansas’s small-town workforces, compared to 6 percent on average for all counties across the state, said Trabert. Consolidating public education’s “non-instructional support services” such as payroll, purchasing, curriculum, and employee services for school districts into regional service centers makes sense, he said. Ten regional centers could easily handle all 90 counties serving rural areas.

Fortune Brainstorm TECH

Charles Koch, CEO of Koch Industries, speaks at a Fortune magazine conference. KPI, the think tank he is a major funder of, is making large-scale efforts that could reduce government services and personnel in Kansas

A 2013 brochure, “How privatization can streamline government, improve services, and reduce costs for Kansas taxpayers,” written by a KPI analyst along with two analysts from the Reason Foundation (a sister nonprofit supported by Koch) laid out the rationale. “Our center will function like a nonprofit counseling and coaching service,” Trabert said. “There is a big lack of leadership in Kansas and that’s what we are trying to provide with our center.”

There is little argument with Trabert’s observation on the leadership vacuum in rural Kansas. And most folks I spoke with expect KPI will find lots of takers for its free services. But KPI is essentially working to help local and municipal governments in Kansas dismantle themselves. And in the absence of a more coherent statewide policy, this effort doesn’t bode well for communities interested in taking charge of their environmental challenges at the county level. In fact, the strategy has the potential to be a highly effective tool of deregulation, as Kansas already lags behind other states in its ability to collect and act on environmental data. That trend, combined with the legacy of the Brownback tax cuts, means it will be harder than ever for Kansas to take environmental action—even if it musters the political will to enact regulations.

Zack Pistora, legislative director of The Sierra Club of Kansas, the leading environmental lobbyist in the state, says that environmental progress in Kansas happens only when private landowners take action. In his view, that attitude has been nowhere near enough to address the state’s mounting challenges.

“Kansas is the caboose on the nation’s environmental train,” Pistora likes to say. There is no government leadership on the environment. There is no accountability, no requirements for transparency. “It’s not part of the Kansas culture to disclose anything.” Tracking toxins released into the soil and water is “darn near impossible.” If local governments downsize their staff the way KPI suggests, the ability to monitor environmental damage—let alone act on it—is likely to be further compromised.

“Kansas is the caboose on the nation’s environmental train,” Pistora likes to say. There is no government leadership on the environment. There is no accountability, no requirements for transparency. “It’s not part of the Kansas culture to disclose anything.” Tracking toxins released into the soil and water is “darn near impossible.” If local governments downsize their staff the way KPI suggests, the ability to monitor environmental damage—let alone act on it—is likely to be further compromised.

Growing up in 1970s Wichita, I’d never heard of the Gyp Hills, arid badlands along the Oklahoma border, a two-and-a-half hour drive southwest of my hometown. Driving into the region across central Kansas’s flat farmland—one, two, three turns—and I rolled into a 30-mile by 30-mile bowl of red rock mesas and buttes. This cloistered world is surrounded by a patchwork of grass-covered hills tacked to the earth by narrow canyons filled with prickly Eastern Red Cedars. It was once Comanche land.

I was there to visit Z Bar, one of the largest ranches in Kansas, 42,560 acres owned by media-mogul-turned-bison-rancher, Ted Turner. Eighteen years ago, Turner launched an ambitious effort to restore the native Kansas prairie through rotational grazing and aggressive tree removal. Nature hurried that recovery along two years ago, when a massive fire burned up everything, including ranch manager Keith Yearout’s home. Even with his bold efforts, the land will take decades to regenerate. Eighty-year-old Turner will be long dead before the land returns to what it was when the last Comanche spent the winter here before moving south into Oklahoma.

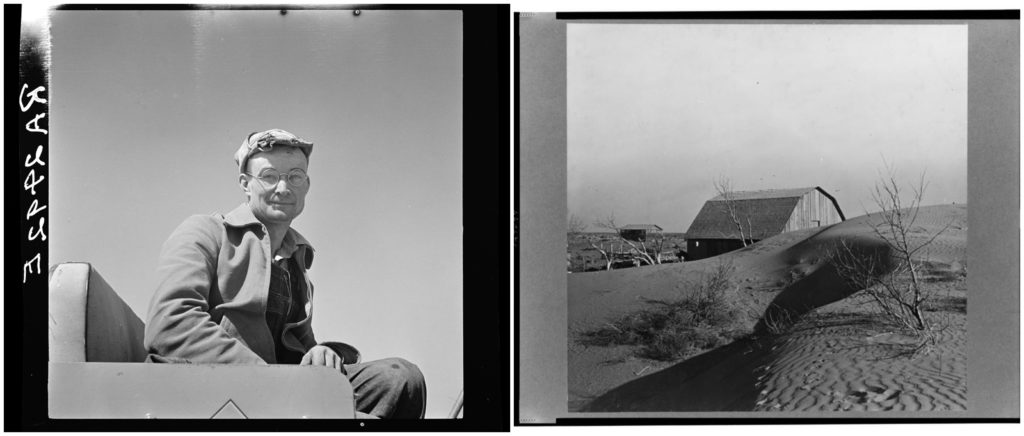

“Kansas could absolutely have another Dust Bowl, anywhere they continuously farm the land,” says Yearout, referencing the country’s largest man-made environmental disaster. Before Turner, the ranch’s fragile, sandy red soils had been over-grazed and over-farmed, leaving a moonscape studded with Old World Bluestem, a non-native grass introduced after the Dust Bowl. Buffalo eat most anything, Yearout says, but they won’t touch that grass. “It will take a long time to heal this land.”

Library of Congress / Arthur Rothstein

A Kansas farmer (left) and farm (right) taken by photographer Arthur Rothstein during the 1930’s Dust Bowl, a period of soil erosion that forced many Kansans off their land. Many conservationists fear that the demise of the Ogallala aquifer may spell a similar disaster

“Our ancestors were just trying to survive out here. It was farm it or lose it for them,” he continues. Too bad no one teaches the Dust Bowl to Kansas’s kids, he says, with a shake of his big head, the braided ends of his mustache brushing his chin.

I heard that sentiment again and again in my travels across the state. Kansans dismiss the Dust Bowl as a stretch of bad weather. Truth is, says Yearout, “the only reason we don’t have another one is because farmers have big, 400-horsepower tractors.” When the winds blow across naked ground, farmers quickly rip the land into ridges that stop loose soil from blowing away, a far from optimal land management practice.

Change is forced on people in Kansas, Yearout says. Not through rules or laws, but out of economic necessity. “Conservation will get better here because it has to.”

With a Democratic governor soon to be running the state, there are signs, already, that minds may be starting to change. Three Republican state legislators recently declared themselves Democrats. Environmental regulation may have a prayer in Kansas.

“The successful farmers I talk to, we disagreed with the state tax cuts, even though we were the beneficiaries,” says Steve Irsik, a Kansas farmer and rancher. “It shouldn’t have been done. Shifting resources from the pubic to private people. Left the whole damn state struggling.”

Describing himself as a “Republican with second thoughts,” Irsik’s family history is similar to Koch’s. Both men built empires on a sturdy base inherited from their fathers. But the rural Kansan fumes when he talks about his fellow citizen from Wichita. The tax cuts championed by Koch knocked the state off its center, Irsik says. Nothing has been the same since.

Describing himself as a “Republican with second thoughts,” Irsik’s family history is similar to Koch’s. Both men built empires on a sturdy base inherited from their fathers. But the rural Kansan fumes when he talks about his fellow citizen from Wichita. The tax cuts championed by Koch knocked the state off its center, Irsik says. Nothing has been the same since.

All of the small town banks are going to close and these little towns are going to die, he says. It’s too late to change that. “If you liked the size of your farm back when and were comfortable with the money you made and you didn’t keep growing, didn’t diversify, you are now out of runway. You are done,” Irisk says. Farmers doubled down on commodity grain, bought more equipment to farm more acres. He says he warned them it was a trap. They wouldn’t listen.

“The Ogallala is a great big lake but it’s out of sight. Everyone knows the well yields are down, but their toilets still flush so they keep pumping water to irrigate fields,” says Irsik. “To get anyone to look down the road just a little ways and reduce water consumption is just damn near impossible. You can’t get it done. I tried.”