KUNC: Water Is Leaving Colorado Farmland For The City — But Will It Ever Return?

A grain silo serves as an advertisement for new homes in Windsor, Colorado, part of the expanding Water Valley development. – Luke Runyon / KUNC

by Luke Runyon, Matt Bloom & Esther Honig | Jun 13, 2018

An old water cliché tells us that “water flows uphill toward money.” It’s an adage born out of people’s frustrations about who benefits when water moves around in the Western U.S., popularized by author Marc Reisner’s 1986 book, “Cadillac Desert.”

Like all persistent folksy sayings, it’s a mix of myth and truth.

But there’s at least one case where it has some validity: the phenomenon known as “buy and dry” along Colorado’s fast-growing, historically agricultural Front Range.

“Buy and dry” describes a class of water transactions that typically involve a municipality or other local government paying the owner of a farm for some or all of their available water rights.

It’s a slow, mostly invisible flow of water from the region’s heritage industry — agriculture — to a new powerhouse: real estate development and urban growth.

The transactions go back decades, with plenty of cautionary tales to guide both farmers and government officials, casting various Front Range cities and Eastern Plains farming communities as both villains and victims.

Concern about the practice has reached a fever pitch. The state’s water plan, adopted in 2015, frowns at buy and dry tactics. Water prices continue to rise. Some alternative methods for leasing water are slowly being implemented, at the same time multi-million dollar checks are passed from developers and city planners to farm families.

The town of Windsor is among Colorado’s fastest growing communities, all of which are clustered on the state’s urban Front Range. Credit Luke Runyon / KUNC

Urban growth is a driver

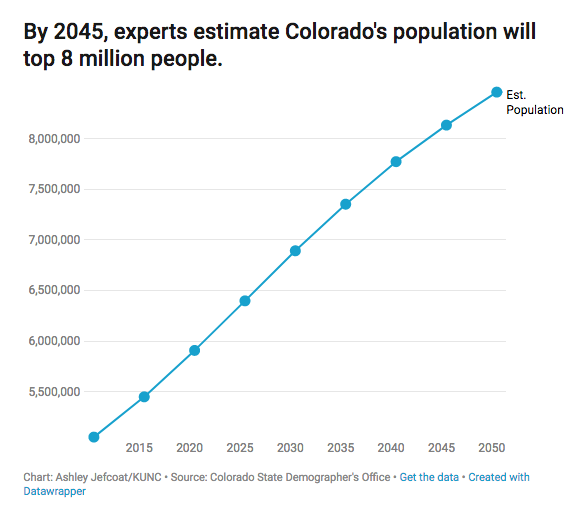

The practice of buy and dry is primarily driven by the growth of water-short cities – of all sizes – along the Front Range. According to Colorado’s State Demography Office, communities along the I-25 corridor in Weld and Larimer counties are the fastest growing. Populations there are increasing at a rate twice as fast as the state as a whole.

Formerly a sleepy farming hamlet, the town of Windsor, has increased its size by 35 percent in less than a decade, with hay and wheat fields giving way to suburban development.

Those new residential and commercial developments have forced the town to draft an ambitious water acquisition plan to support the infrastructure influx, calling for the purchase of four times the amount of water rights currently owned.

The town expects to add at least another 14,000 residents to its current 23,000 by 2040.

“With growth in this area, we’re all competing for that water,” says Dennis Wagner, Windsor’s director of engineering, “and so the supply isn’t getting any bigger, but the demand is.”

Windsor, like many fast-growing Front Range communities, sees agricultural water as a viable source to supplement future growth. As recently as May, Windsor purchased water rights from at least two different farming families, according to allotment contracts from the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District.

One purchase was of units of water within the Colorado-Big Thompson Project from the John Ernest Lucken Revocable Trust. The other with the Andrew H. Blase Family Trust.

In both cases Wagner says he doesn’t know whether the town’s purchases led to farms “drying up.”

“I’m not sure of what’s happened to those farms,” he said. “Whether they still have enough water rights to irrigate or whether they’ve reduced the farming acreage.”

Wagner added that Windsor, unlike other cities, has not specifically purchased farms to own them and take the water off them. When asked about the likelihood of the town doing that, Wagner said it very well could.

“As we all know, it is happening,” he said.

Outside Greeley, Colorado, a center pivot irrigation system waters a field of corn. Water owned by farmers has become increasingly valuable to nearby cities. – Credit Esther Honig / KUNC and Harvest Public Media

Water rights worth millions

For farmers in the West, access to water is a key part of making agriculture possible in an arid region. Without irrigation farmers are significantly limited on the range of crops they can grow and in the profitability of the land they own.

With commodity crop and milk prices at low points, selling water rights can help make a farm operation whole.

That’s the case for Colorado dairy farmer Timothy Bernhardt, just down the road from Windsor in Milliken. The Bernhardt family has farmed there since the 1920s. Access to water to quench the thirst of his 900 dairy cows is essential, Bernhardt says.

“Cattle drink a lot of water, so about 50 to 100 gallons of water a day,” he says. “So it’s critical for milk production because milk is made up mostly of water.”

In May Bernhardt and his brother made the choice to sell 175 units of water within the Colorado-Big Thompson Project — about 57 million gallons. According to Milliken officials, Bernhardt’s water was purchased for more than $4.72 million.

That money will be used to pay off debt, Bernhardt says. Like many businesses, farms rely on loans and credit to operate and the brothers wanted to pay it off because they’re each older than 60 and looking at retirement.

While their children will continue to farm the family land, they aren’t interested in running the dairy. When they retire, the dairy ends with them.

Over the years, how Bernhardt sees his water and how important it is to him has changed.

When he was young, just starting out, it meant survival. The water was integral to his operation, closely guarded.

“But then it’s like OK, it’s just another asset. When you’re getting older, it’s just like another asset that you have,” he says.

Another factor that influenced him to sell was the price of milk, which is down by about 10 percent from last year. Bernhardt said these lean times are when farmers consider selling off water rights.

“Because there are some times when things are pretty tough that you need to do what you can do to survive,” he says.

Some cities offer farmers the option to rent water back. Those lease agreements aren’t likely a permanent solution. During extended dry times the city could choose not to lease water and instead use it for their residents.

Cautionary tales

There’s no arm-twisting in buy and dry, cities are often quick to say. These transactions involve willing buyers and sellers. Cities get what they need — new water supplies — and farm families get an opportunity to pay off debt, make on-farm upgrades or retire.

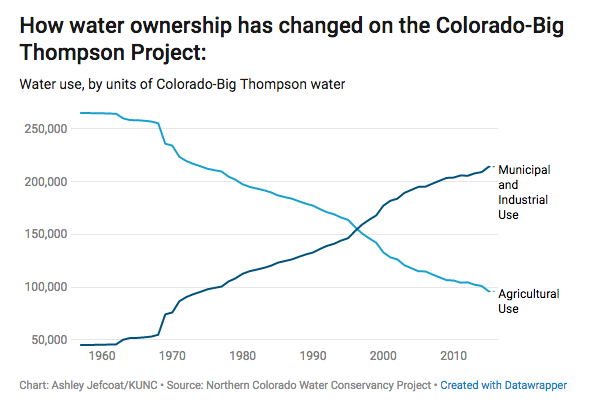

But on a regional-scale, water managers and government officials are troubled. Water flowing from farms to the Front Range means a movement of power and economic activity, from rural areas to cities. Take the Colorado-Big Thompson Project as an example.

When the vast network of reservoirs was originally built in the 1930s to transport water from the state’s wetter Western Slope to the east, agriculture was the majority user of its stored water. Today, 70% of the project’s water is used by municipalities and industry.

Conversations about buy and dry often turn to the Arkansas River valley and the communities of Crowley, Ordway and Sugar City. Water managers don’t really have to imagine what a future of rampant buy and dry could look like. It has already happened there.

“If you go to the Arkansas Basin and drive around you’ll see the net result of that, which is dry land down there and not irrigated farmland,” says Sean Cronin, director of the St. Vrain and Left Hand Water Conservancy District in Boulder County. “The landscape looks fundamentally different than when the land was being irrigated.”

The entire river valley took a hit when those farmlands were dried up, Cronin says. Water managers have a responsibility to keep the same thing from happening in other parts of the state where demands for water have begun to move rights from farms to cities.

“If you’re looking at it regionally, in terms of the overall economy for Colorado having a diverse economy with vibrant cities and agriculture and you find that its shifting from one way to the other and we’re losing some of our diversification then I think it’s a cause for concern,” he says.

Cronin and a handful of other water managers in the South Platte Regional Opportunities Working Group recently started a conversation about what it would take to allow Front Range cities to keep growing, without draining farms in the process. It looked like at least three — maybe four — new reservoirs positioned along the South Platte River to the stateline with Nebraska to supplement water supplies for cities and farmers.

Cronin cautions that these are preliminary discussions.

He calls the discussion of new reservoirs a “generational” one — if the idea gains enough supporters for it to happen at all. Large-scale water projects often take decades in planning, permitting and litigation before a shovel hits the ground. This one would likely follow a similar timeline, Cronin says. Questions still linger about how much it would cost, another big hurdle to bringing it to fruition.

In the meantime water will continue to move off farmland to keep Colorado’s cities and their thirsty populations well-watered.

Editor’s Note: This story has been corrected to clarify that Bernhardt’s family will continue the agricultural side of the family farm, but not the dairy. The price of Bernhardt’s water was updated to reflect the value given by the town of Miliken.

This story is part of a project covering the Colorado River, produced by KUNC and supported through a Walton Family Foundation grant. KUNC is solely responsible for its editorial content.