Journal Sentinel: Dairy farmers are in crisis — and it could change Wisconsin forever

Chuck and Sue Spaulding have partnered with their daughter and her husband to run S & S Dairy.

Mark Hoffman/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

by Rick Barrett | February 21, 2019

There was a time when the soft glow of barn lights dotted Wisconsin’s rural landscape like stars in a constellation, connecting families who labored into the night milking cows, feeding calves and finishing chores.

Hundreds of those barns are dark now, the cows gone, the hum of milking machines silenced.

“All of our neighbors are done,” said Sue Spaulding, a dairy farmer near Shell Lake, in Washburn County.

She and her husband, Chuck, soldier on, milking about 60 cows on their 300-acre farm that Chuck bought when he was only 17.

Seven years ago, the Spauldings borrowed heavily to modernize their barn and position things for the future.

“It looked good on paper,” Sue said.

But in late 2014, farm milk prices started to plummet. The downturn, fueled by overproduction and failing export markets, has lasted more than four years and has wiped out dairy farms from Maine to California.

The price farmers receive for their milk has fallen nearly 40 percent.

“This downward cycle has been brutal,” said Kevin Schoessow, a University of Wisconsin-Extension agent in Washburn County.

Wisconsin lost almost 700 dairy farms in 2018, an unprecedented rate of nearly two a day. Most were small operations unable to survive farm milk prices that, adjusted for inflation, were among the lowest in a half-century.

As of Feb. 1, Wisconsin had 8,046 dairy herds, down 40 percent from 10 years earlier, according to state Department of Agriculture data.

Remaining dairy farmers have burned through their farm equity and credit to remain in business. Often, at least one family member works an off-farm job to put groceries on the table or pay for health insurance. Some work double shifts, farming during the day then heading to a local factory for the night. It’s exhausting, but it keeps families in agriculture and preserves a cherished way of life.

Much of Wisconsin’s $88 billion farm economy hangs in the balance. Hundreds of towns across the state depend on the money that dairy farmers spend at equipment dealerships, feed mills, hardware stores, cafes and scores of other businesses.

Each dollar of net farm income results in an additional 60 cents of economic activity, according to University of Wisconsin research.

This spring, though, farmers face crucial decisions. Some are running out of feed for their cattle. Do they seek operating loans to plant crops for livestock rations? Or do they quit and cut their losses that can add up to thousands of dollars a month?

Often the fate of their livelihood isn’t in their hands.

“Banks are wary of taking on more risk,” said Michael Slattery, an economic adviser for Wisconsin Farmers Union, a trade group based in Chippewa Falls.

Nearly every dollar the Spauldings have earned from their milk the last few years has gone toward their debts and farm insurance, leaving them with little income except for Chuck’s Social Security check and selling some livestock and hay.

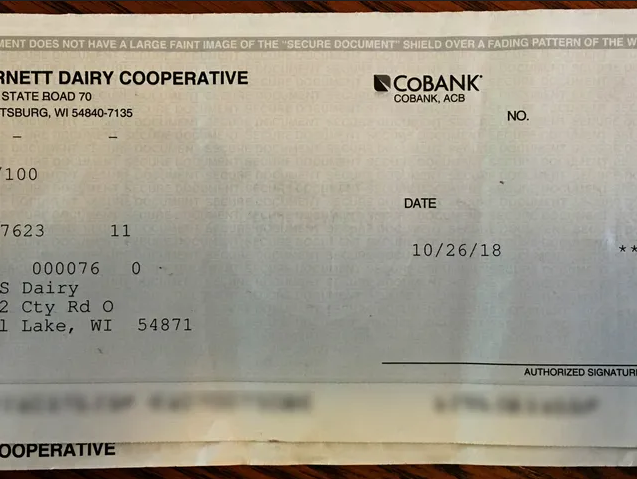

Their milk checks, after deductions are taken out, come imprinted: “Void.”

A check from the dairy cooperative is shown voided because the bank has first dibs on money from the milk sold by S & S Dairy.

Mark Hoffman, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

“It’s been such a struggle just to keep things going,” Sue said. “We have managed, but now it is getting hard to pay even our basic everyday bills. I don’t know how much longer we can do this.”

As Sue spoke, she faced a $900 electric bill due in only four days. The barn needs repairs and there’s farm equipment that should have been replaced long ago.

“We are running out of resources,” she said. “It’s hard to sit here and watch things fall apart.”

How Wisconsin became ‘America’s Dairyland’

Wisconsin didn’t start out as a dairy state.

In the mid-1800s, one-sixth of the wheat grown in the United States came from Wisconsin. White settlers from the East Coast didn’t need much initial investment and found the crop easy to manage.

But varying yields, rising competition from neighboring states and an insect infestation forced wheat farmers to consider alternatives. Dairy farming emerged in the latter half of the century as a better fit for the state’s terrain and climate.

By the turn of the 20th century, 90 percent of Wisconsin farms had dairy cows, and by World War I the state led the nation in butter and cheese production. It held the milk production title until 1993 when that recognition went to California.

Wisconsin, though, remains No. 1 in terms of connecting dairy with its cultural identity.

For nearly 80 years, “America’s Dairyland” has been imprinted on the state’s license plates. And for the last four decades, foam Cheesehead wedges have been a staple at sporting events and in tourist shops. Dairy contributes more to Wisconsin’s economy than citrus does to Florida or potatoes to Idaho, and more than a quarter of the nation’s cheese comes out of the state.

For all the pride Wisconsin takes in its heritage, some national consumer trends have been headed in a different direction. Sales of milk as a beverage have fallen steadily since the 1970s, with fewer parents encouraging their children to drink milk than ever before. Soy milk and almond milk — which dairy farmers point out aren’t real milk — and scores of sports drinks have flooded the beverage market.

And although consumption of cheese, yogurt and butter have all increased, they’ve not always kept pace with runaway production. Today, for instance, U.S. commercial and government cheese stockpiles are at about 1 billion pounds — the highest level in a century.

At the same time, foreign markets for American dairy products have shrunk in response to tariffs that President Donald Trump placed on foreign steel and aluminum. Cheese shipments to China have fallen almost 65 percent, according to industry figures, and exports to Mexico are down more than 10 percent.

Mexico and Canada have targeted rural America as a way to punish Trump, and the economic harm could be felt for years to come, said Laurie Fischer, CEO of the American Dairy Coalition.

“This should have changed in November when Trump declared success with his newly rechristened U.S.-Canada-Mexico Trade Agreement replacing NAFTA,” Fischer said.

“In retrospect, it was a disingenuous statement: The administration has not lifted steel and aluminum tariffs on Mexican and Canadian products, and in response, those countries are refusing to (ratify) the pact or lift retaliatory tariffs, impacting dairy products and other items.”

Wisconsin farmers are getting about $10 million in payments from Trump’s farm bailout program announced late last year. It was designed to help producers of milk, pork, soybeans, corn and other commodities who have seen prices tumble in trade battles.

A 55-cow dairy farm would receive a one-time payment of $725 from the bailout but stood to lose between $36,000 and $48,000 in income last year from low milk prices, according to the Wisconsin Farmers Union. A 290-cow dairy would get $4,905 but would lose several hundred thousand dollars.

Further, dairy farmers have only been getting about 25 percent of the average retail price for cheese, the lowest portion since 2012, according to Fischer.

“There’s no magic bullet on the horizon,” she said. “A shakeout will continue in the dairy sector until markets stabilize and supply and demand realign. Until then, dairy professionals at all levels are working on a day-by-day, if not hour-by-hour, basis to keep their operations afloat.”

Farmers hurt from being too productive

The prices farmers receive for their unprocessed, unpasteurized milk are largely determined by the forces of supply and demand, and government programs.

Minimum prices are set by the U.S. Department of Agriculture using complicated formulas based on the wholesale market value of various dairy products such as cheese, butter and whey.

Many farmers see themselves as pawns in an agricultural system stacked against them. Faced with few options to control the price for what they produce, they ramp up production and hope markets don’t buckle under the strain.

Dairy farmers don’t even know what they’ll be paid for their milk until 30 days after it’s hauled off the farm.

“Every time we see the price go up a little it makes us very hopeful. And then when it drops … everybody goes back to feeling pretty awful,” Fischer said.

In 2012, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker announced an incentive program to produce, as a state, 30 billion pounds of milk a year by 2020 — a 15 percent increase. The state offered farmers grants for business planning, facility engineering and animal nutrition. The program, “Grow Wisconsin Dairy 30×20,” required them to put up their own money as well.

Despite record production every year since 2002, Walker urged farmers to step it up even more. “The reality,” he said, “is the growth is not fast enough for the opportunities that are here before us.”

Dairy farmers not only met the challenge, they reached 30 billion pounds in 2016 — four years ahead of schedule.

By then, however, the market had turned and many dairy farmers were having trouble breaking even on their new investments.

Some felt duped by the agribusiness system.

“The more surplus farmers produce, the lower the price of agricultural commodities for food processors,” said Kara O’Connor, government relations director for the Wisconsin Farmers Union.

“All of the most powerful players in the industry, except the farmer, benefit from overproduction.”

The amount farmers are paid for their milk varies monthly based on the USDA price, individual contracts, quality and other factors. Some farmers say they’ve been getting around $15 for every hundred pounds of milk they produce, roughly 12 gallons. Their costs: $20 or higher.

These are like prices from 40 years ago, said Dennis Rosen, who recently quit milking cows at his St. Croix County farm.

Back then, there were 39 dairy farms within 20 miles of Rosen’s home. Of those farms, only three are left.

“We used to live in a very vibrant area of family agriculture,” he said.

With collapsed prices of milk, grain and other commodities, many farmers have lost money for months at a time. At some point, the losses become unsustainable.

“Just ask any of the 36 dairy farmers who are no longer farming in my neck of the woods today,” Rosen said.

Some farmers have flushed milk down the barn drain because they couldn’t find a processing plant to take it.

That happened in January at Laura Binder’s 70-cow dairy farm near Marshfield.

“We no longer have a dairy plant to ship to, so we are dumping our milk,” Laura said. “What a waste of money.”

Farm auctions have become an all too common occurrence in her area.

“Honestly, I don’t think it’s going to get any better,” she said. “I just think it’s going to keep going down until all that’s left are mega-size farms. There won’t be any place for little farms.”

Some farmers have shot calves because the newborn animals had no market value and were considered too expensive to raise for beef.

In December, an Iowa farmer posted Facebook photos of calves he’d killed, trying to make a point of how desperate things were. Shortly afterward his milk cooperative, Prairie Farms, dropped him as a member, according to Steven Potter, the farmer’s brother in Preston, Iowa.

“I don’t know what he was thinking,” Potter said.

More Wisconsin farmers are calling Farm Aid crisis line

The stress farmers have endured in trying to keep everything together has been overwhelming, especially on farms passed down for generations. Nobody wants to be the one to close the gates.

“It feels like you’ve failed,” said Schoessow, the UW-Extension agent.

Joe Schroeder answers the crisis line for Farm Aid, a group launched during the farm crisis of the mid-1980s and known for its annual concerts organized by Willie Nelson, John Mellencamp, Neil Young and Dave Matthews.

Schroeder has talked with farmers in the darkest periods of their lives. He’s kept some from committing suicide; he’s convinced others to get guns out of their house to avoid rash decisions.

These days, from his base in Cambridge, Mass., he’s getting more calls from Wisconsin dairy farmers whose lives have gone off the rails.

“They’re often the farmers who have the fewest options, the toughest ones to help,” Schroeder said.

Jeff Ditzenberger has been in their shoes. One summer night he walked into an abandoned house near his farm in Green County, lit a fire, and waited to die.

Following months of mental health issues, and unable to get help from a rural health system lacking resources, he planned his own death that August evening in 1992.

“Take the worst day, the worst feeling you’ve ever had … multiply that by a hundred. Add 10. Then you kind of get it,” he said.

Jeff Ditzenberger has become a lifeline for other farmers who’ve contemplated suicide.

Mark Hoffman/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

The flames crept up the walls, and the house filled with smoke.

“You get a sense of morbid peace,” he said, “because it’s like you won’t be a burden or a disappointment to anybody anymore.”

At the last moment he changed his mind and hurried out of the burning building.

“Thankfully, I failed miserably” at suicide, he said.

He’s since started a mental health support group for men, and he’s spoken with many farmers struggling with stress, depression and thoughts of ending their lives.

“I have caught more of my friends in the middle of their suicide plots than I care to mention,” Ditzenberger said. “Suicide doesn’t give a sh– what your occupation is. It’s just wicked.”

Agency looks for ways to help farmers

The Wisconsin Farm Center, part of the state Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection, has been getting about 200 calls a month on its toll-free crisis line.

The Farm Center offers farmers a wide range of free services including mediation with creditors. It also offers vouchers that farmers and their families can use to get counseling.

The staff has decades of experience in agriculture.

“They understand what people are going through, and they’re really good listeners,” said Farm Center Director Kathy Schmitt.

The agency looks for ways to keep farms in business or find an exit strategy.

“We will come right to your kitchen table, or if you want to meet at a McDonald’s we will do that too. It’s whatever you feel comfortable with,” Schmitt said. “Some creditors will accept reduced amounts. And even if we can’t come to an agreement, being able to talk it through with them is good for the relationship.”

Federal court data shows that western Wisconsin had the highest number of Chapter 12 farm bankruptcies in the nation in 2017. And that’s only a glimpse into the dairy crisis since Chapter 12 is a relatively rare tool used in farm closures.

It allows farmers to “cram down” secured debt such as land mortgages to a more affordable level.

“But one of the big problems is that it cannot be used by farmers whose debt exceeds $4,153,150. That sounds like a big number, but in the dairy farming world where equipment, machinery, feed and operating expenses are very high, it is not,” said Elizabeth Rich, an attorney from Plymouth and president of the Farm-to-Consumer Legal Defense Fund Foundation.

“Fifth- and sixth-generation dairy farmers are losing their farms; many are killing themselves. We can and must do better,” she said.

Chuck and Sue Spaulding invested heavily in their dairy farm when milk prices were high. They are struggling to save their farm

First stress, then stroke

The Spauldings were one of those families who turned to the Wisconsin Farm Center in January.

The question was whether time was too short, and the problems too severe.

In October 2017, Chuck had a stroke.

He was out raking hay, then put the tractor away and headed into the house for a glass of water. His hands were numb that day, but he figured it was from the vibrations of steering the tractor.

Then he dropped the glass. He was on the kitchen floor trying to clean up the mess, “talking mumbo jumbo,” as Sue recalls.

She called her son-in-law to come over right away.

“We drove so fast to the hospital we had the cops chasing us,” Sue said.

Chuck was flown to Eau Claire for treatment. The stroke left him paralyzed. He couldn’t talk, and for a while he couldn’t remember his wife’s name.

Then, back home for a day, he had a brain hemorrhage.

Another emergency medical flight, this time to a hospital in Marshfield.

Now, after about a year of physical therapy, he’s able to work on the farm again but not like before. His right side is weak; he can manage driving a tractor but not a car.

Still, “he is a true miracle,” Sue said.

Chuck remains hopeful that milk prices will turn around, Sue said, like they did after previous slumps that lasted a year or two. But this one is much worse in that it’s dragged on for such a long time.

“It’s almost like there’s hope, but then there isn’t,” Sue said.

Adding another layer of stress, the Spauldings briefly lost their milk buyer — a blow that could have spelled the end of their dairy operation.

She and Chuck sought a loan from their local bank to keep the farm afloat until money starts coming in from the new milk buyer.

“I am scared. If we lose the farm, we lose our home, too,” Sue said. “We just remain in survival mode.”

Sue Spaulding is shown with a 3-week-old calf, Hope, which had some health issues. It died a few days later.

Mark Hoffman / Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Dairy farms are too productive

Though dairy farms of every size are struggling, some remain profitable if their operating costs are low enough to handle fallen milk prices or they have enough income from other sources.

Very large dairy farms, which can have anywhere from 1,000 to 8,000 cows or more, benefit from economies of scale — meaning they can negotiate lower prices for necessities such as animal feed and are better financed to weather a downturn.

“The big dairies almost seem to be in perennial expansion mode,” said Hans Breitenmoser Jr., who has a 430-cow farm in Lincoln County.

“There are farms pumping out a ferocious amount of milk, whereas a generation ago if farms fell by the wayside, production also went down,” he said.

The current slump, now in its fifth year, has lasted long enough that farmers are questioning whether it’s become the new normal in dairy.

“I will be perfectly honest, I am scared about that,” Breitenmoser said.

Dairy farms are so productive these days, partly from improved cow genetics, they can quickly flood markets.

“We are very good at what we do,” Breitenmoser said.

Further, farmers who have invested heavily in their milking operation can’t afford to just turn off the spigot. Instead, as profit margins shrink, they try to squeeze out ever-higher amounts of milk to cover their costs — even if it adds to the overall surplus.

Some farmers say the U.S. needs a milk supply management system, like Canada has, that imposes production quotas and protects farmers’ income.

Critics of Canada’s system say it has resulted in trade barriers to U.S. dairy products.

“But whether the answer is a system similar to Canada’s supply management program or something completely different, we can’t just sit back and continue down the same current path without trying to find something that actually works for farmers,” Brad Rach, dairy director for the National Farmers Organization, wrote in a blog.

Too little, too late?

Even quitting can be challenging.

Twenty years ago, a farmer could hold a farm closure auction and other farmers in the area would come and buy almost everything. There aren’t as many buyers now, said Jim Goodman, a former organic dairy farmer from Wonewoc and president of the group Family Farm Defenders.

Banks have applied more pressure, and not just in Wisconsin.

“Three young farmers in foreclosure that I know of and herds being liquidated,” a country lawyer in New York state said in a recent email to Goodman.

“Young, unseasoned people in shell shock. Feed companies suing farmers for past-due feed bills. … There is a crying need for emergency help right now to get through the winter or there is going to be another round of sell-offs.”

Last fall, Goodman called it quits after more than 40 years of milking cows on his third-generation family farm. He sold off his 45-cow herd, whose lineage could be traced back more than a century.

“If there was light at the end of the tunnel, and you could say things would be looking up by the summer, that would be one thing. But nobody has an idea that’s going to happen,” he said.

One positive note in the recent farm bill passed by Congress and signed into law by Trump is an improved income insurance plan — partially funded by the government and from premiums paid by farmers — to help when the gap between milk prices and cattle feed prices widens to a certain point.

Still, it’s no substitute for a strong marketplace.

“The farmers I know would rather receive fair prices for their products at the farm gate than having to live with the stress of volatile markets and the unknowns of whether emergency relief and insurance will kick in,” said O’Connor with the Wisconsin Farmers Union.

Even if milk prices improve this year, it could be too little, too late, for many farmers who have “simply run out of financial and emotional strength to continue,” said Peter Hardin, publisher of The Milkweed, a dairy industry publication in Brooklyn, Wisconsin.

“You can tell people that things are going to get better, but until they see it in their milk checks they won’t — and shouldn’t — believe it,” Hardin said. “The only comparable example now is the Great Depression.”

click to play –

Sue and Chuck Spaulding have partnered with their daughter and her husband to run the farm, S & S Dairy, in Shell Lake.

Mark Hoffman, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Trying to hang on

The Spauldings say they’ll hang on for as long as they possibly can.

“Chuck has worked his whole life for this place,” Sue said, and he wants to give it another year before deciding whether to sell the cows.

They raised seven children on the farm, through a blended family from previous marriages, and they’ve been through some lean years.

“But we were always able to put food on the table, have clothes for the kids, and live a good life,” Sue said. “Now, I’m glad we don’t have little kids.”

The Spauldings’ youngest daughter and son-in-law, Christy and Jeremy Spexet, also rely on the farm for their livelihood. They live in a mobile home nearby and put in long hours to keep the milking operation going.

“We are lucky to have them,” Sue said.

But Chuck and Sue cannot afford to pay them much. In a nod to both desperation and technology, Sue started a GoFundMe campaign to get some help from the public. Other farmers have done the same.

“We set a $30,000 goal for our campaign because we didn’t want to scare people away,” Sue said. “But we probably owe about a quarter of a million dollars.”

“I feel bad for reaching out because I know there are a lot of other people worse off. But at this point even a $10 donation feels like $100,” she said.

She and Chuck would like the farm to be their legacy, a place for their family to carry on traditions. A lot of other farmers wanted that too, but it wasn’t meant to be.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Sue said.

Chuck Spaulding moves his 1964 John Deere tractor into a shed while doing chores on their farm in Shell Lake.

Mark Hoffman/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Anger at a broken system

Danielle Endvick, from Chippewa County, said her dream of becoming a dairy farmer died when her father’s farm shut down.

“From the time I was a young girl, trailing dad out to the barn to feed calves, I remember boldly declaring my plans for my future: ‘I’m going to be a farmer, too,’” she said.

“My world revolved around our dairy farm. I woke early to help dad with morning chores and headed straight back to the barn when the school bus dropped me off after school. Some of my best memories were those chore times spent with dad, ambling along beneath the whitewashed barn beams.”

She also remembers the farm slipping away from her father as, month after month, the milk checks kept getting smaller.

“Another price drop … Dad had become a regular at our small-town bank. He was a sound farm manager and worked full time at the local feed mill for the insurance and extra paycheck. But with milk prices on an ever dipping-and-diving roller coaster, our chances of digging out looked slim,” she said.

A few years after she left the farm, her father sold the herd. As she saw dairy farms falling apart in the current crisis, she wrote a remembrance of that time not long ago.

“I remember the dreary day spent following the cattle broker as he walked through the barn, eyeing up the cows I’d raised from calves, as he turned over in his mind which would bring the prettiest penny. And I remember all too well that emotional last milking, where dad and I again found ourselves gathered around the bulk tank, this time with my infant son, Blake, who slept peacefully in a corner of the milk house.”

“When the cattle trailer backed up beside the milk house, our big Brown Swiss, Brownie, was among the first to load. I paused to scratch her head one last time before nudging her across the gutter and out the door. One by one the cows filed out, closing a chapter on the farm.”

Later, Endvick relived the pain as she watched her uncle’s cows head out the door of his barn one last time.

“Two farms erased from Wisconsin’s dairy industry,” she said. “Two among thousands lost these past few years.”

In 2015, Endvick realized her dream of having her own farm, now named Runamuck Ranch, where she and her husband, Jesse, raise beef cattle, goats and chickens.

But they’re not milking cows.

“Some days I’m thankful for the foresight dad had. A lifetime in the dairy industry told him that we were on a runaway train that was only headed for heartache,” Endvick said.

“Other days I’m angry that I didn’t try to fight it out and do what I love, no matter how hard the struggle. But … as I see fear stirring in my friends who are dairy farming, I’m angry at a system that has been broken for so many years.”

Andrew Mollica of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel staff contributed to this report.