Indy Week: 2019 Food Triangle: Firsthand Foods Is Disrupting the Way Meat Is Raised and Eaten in the Triangle

by Layla Khoury-Hanold | May 6, 2019

From the ingredients splayed on the wooden board, I nestle rosy slices of meat inside a lettuce leaf and dip it in a chili-garlic sauce. The flavor is so rich, so flavorful, that I forget I’m eating grilled pork collar, not ribeye.

This is the finale from The Durham’s pork-centric winter luau menu, which also includes “spam” musubi, pressed pork shoulder atop a square of sticky rice; crispy yet pleasingly chewy pig ears dusted in Chinese five spice; and an unctuous stew bobbing with melting cubes of pork belly and juicy-crisp pig tail. Each course (except dessert) features pork from four different North Carolina farms, all sourced through Firsthand Foods, a Durham-based company that supplies local restaurants, institutions, and consumers with pasture-raised meat from small, local farms.

“The important thing about local meat production is you can raise the most beautiful animals in the world and do it super consciously and humanely, but if you don’t have appropriate processing and distribution, that kind of goes out the window,” says Andrea Reusing, chef-owner of Lantern in Chapel Hill and the executive chef of The Durham. “Fifteen years ago, you couldn’t call someone and get pork, and now I can, and now many chefs in North Carolina can, and many institutions can as well. That is largely because of Jennifer and Tina.”

She’s referring to Tina Prevatte Levy and Jennifer Curtis, who co-founded Firsthand Foods in 2010. Since then, they’ve changed the way that meat is raised and consumed in the Triangle by helping farmers find new markets for local beef and pork and providing valuable feedback on improving farming methods, ultimately creating a more sustainable and delicious product.

No matter its sustainability, however, meat can be a polarizing topic. While the locavore food movement has prompted consumers to pay more attention to where their food is coming from, it’s a lot easier to imagine a carrot being plucked from the soil than it is to picture the slaughtering and processing of a pig. But at a time when meat production is under increased scrutiny, it’s more important than ever to know where your meat comes from. And even if you’re a vegan, there’s no denying the positive impact that food hubs like Firsthand Foods have on the local food economy and our collective well-being.

In 2008, while pursuing an MBA in city and regional planning at UNC-Chapel Hill, Prevatte Levy met Curtis, then the project director of N.C. Choices, an extension of the Center for Environmental Farming Systems. There, Curtis was tasked with building a network for pasture-based livestock producers and driving economic development for smaller producers. Curtis discovered that there was a disconnect in the local food chain: Farmers and processors weren’t talking to one another, so there wasn’t much of a market. Yet there were lots of producers who wanted to be part of the local marketplace but lacked the time and expertise to market and distribute their meat.

With Prevatte Levy’s business savvy and Curtis’s relationships with farmers, as well as the backing of N.C. Choices, the pair began exploring what a business model would look like for a company that acted as a go-between for farmers and chefs.

At the end of 2010, Firsthand Foods was in its nascent stages when Prevatte Levy and Curtis met Seth Gross, who was preparing to open Bull City Burger and Brewery in Durham. Initially, the pair thought they’d focus on pork, but they switched gears when they saw that Gross was committed to using locally raised beef. To source the quantity of beef he needed, Gross would’ve had to work with up to twenty different farmers and multiple processors, deal with variable prices, and endure a logistical nightmare to coordinate trucking and delivery.

“It was a relief for Bull City Burger and Brewery for Firsthand to step in and consolidate that step in the process,” Prevatte Levy says. “So that all he has to do is work with one person and place one order and know he’s going to get a fresh, quality product and get it consistently and reliably.”

This also gave North Carolina farmers a reason to keep their cattle and raise the beef at home, instead of shipping it out of state, thus keeping more money in the local economy.

Firsthand Foods continued to grow its wholesale business as a rising tide of independently owned Durham restaurants emerged, many of them willing to pay a premium for local, pasture-raised meat. And because Firsthand works with processors, rather than cutting meat in-house, it can be a custom shop to provide whatever cuts chefs need.

Even if a restaurant doesn’t explicitly list Firsthand on its menu, you needn’t look further than Firsthand’s Tour de Pork contest to realize its reach. Last summer, diners who ordered pork-centric dishes at twenty participating Durham restaurants could get their “passpork” stamped to earn points to cash in for prizes. (The grand prize was two tickets to The Durham’s nose-to-tail winter luau feast.)

“Diners really understand the community it takes to sell this product, that it takes buy-in from all these local restaurants that are committed to sourcing local, pasture-raised meats from small, local farms,” Prevatte Levy says. “It’s a cool way for diners to visualize it and experience it. And it helps diners discover new restaurants too.”

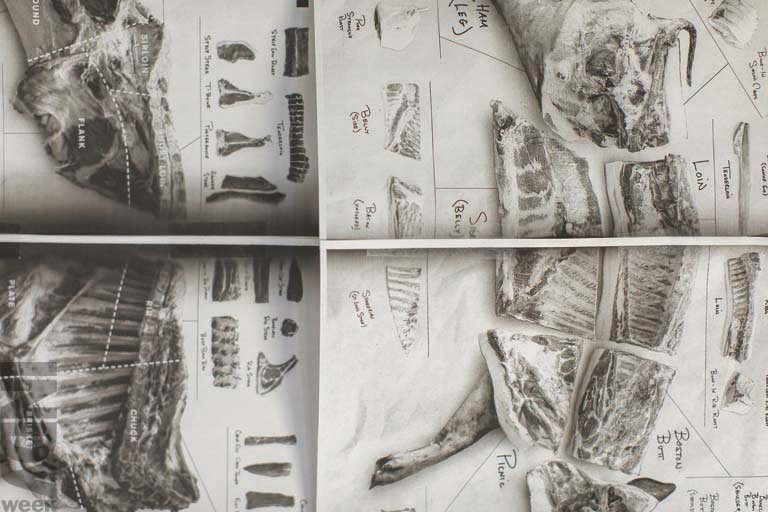

Last year, Firsthand hired sales manager Allyn Bryson, whose job involves the weekly task of “meat math,” working with chefs to find a home for every cut, including tongues, jowls, and hearts. Bryson then sends cut sheets to processors, oversees distribution to restaurants, and provides processors’ feedback to farmers.

Firsthand Foods

“Meat Math” at Firsthand Foods

Closing the feedback loop has been key to Firsthand’s success. Farmers receive a detailed evaluation with a photo and scores for criteria such as marbling, color, carcass weight, and loin eye size. Farmers use that data to adjust things such as breed stock, pasture rotation, and feed.

“I think the feedback they get on their carcass is as important as the money we pay them,” Curtis says.

By assigning values to these criteria, Firsthand has also developed an internal model to evaluate performance and show farmers how different factors play out among chefs. This, in turn, affects farmers’ decision-making and profitability by, for example, helping them figure out the sweet spot where most of the hog’s weight is concentrated in the most expensive cuts. The model also rewards quality over quantity—hog farmers can see how they rank among their peers, and most years, top scorers receive an annual premium. Beef producers whose beef ranks mid-choice or higher receive a quarterly premium.

With the restaurant sector of its business well-established, Firsthand started making inroads with local institutions. When a customer such as UNC-Chapel Hill, who became Firsthand’s first university client in 2012, buys a couple of hundred pounds of sausage a month, it’s a boon to fulfilling Firsthand’s whole-animal mission. Currently, Firsthand supplies beef and pork to Duke University and SAS, which has a mandate to source 20 percent of its food locally.

It’s easier to get buy-in with an institutional mandate, but Firsthand has made strides into public schools through initiatives such as Durham Bowls, which pairs local chefs with child nutrition directors to develop recipes featuring local, sustainable products that meet the federally mandated per-meal budget. (Prevatte Levy serves on Durham Bowls’ board.) Teams recently competed in a cook-off in which students voted on their favorites, and the winning dishes are now being served once a month in all forty-seven Durham public schools, including a Cuban pork and rice dish developed by chef Roberto Copa Matos from COPA and food service manager Gwendolyn Coley from George Watts Elementary School. To serve all forty-seven schools this one dish, Firsthand sold nearly one thousand pounds of pork shoulder.

Though Firsthand was founded as a wholesale business, it hopes to focus more on retail next. Besides expanding its retail reach beyond its twenty specialty accounts, Firsthand puts a premium on consumer education.

“When we started, we were really adamant—and still are—about transparency. Like really, how does it work? And where is it coming from?” Curtis says. “Conventional animal production and slaughter has just gotten so huge. It’s just a few companies, they own everything, and they’re at a scale that’s hard to imagine. Four hundred hogs a minute slaughtered in one facility. That is not comfortable for us. We’d rather feel like it’s being done at a regional, local scale that we can imagine, and that it feels right.”