ILSR: In Cities Around the Country, New Action on Commercial Affordability

by Olivia LaVecchia | March 27, 2018

In many U.S. cities, finding and keeping an affordable location has become a major challenge for independent businesses. Two years ago, we took an in-depth look at the issue in our report, Affordable Space: How Rising Commercial Rents Are Threatening Independent Businesses, and What Cities Are Doing About It. We examined what’s causing the problem — from real estate financing that compels developers to exclude independent businesses, to the declining supply of small spaces — and also outlined six strategies that cities were beginning to use to address it.

Now, one of those strategies is catching on: Set-asides for local businesses in new development. It’s a strategy that requires developers to reserve, or “set aside,” space for small or local businesses in new construction, and it can help ensure that a built environment that’s suited to small businesses isn’t replaced with one designed for chains. In three cities — New York, Portland, Ore., and Boulder, Colo. — there are new programs that offer examples for how set-asides can work. Here’s what they look like.

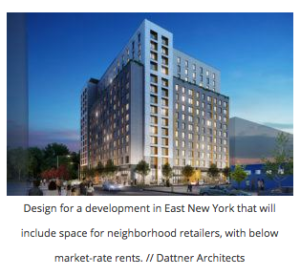

1. New York City

In a neighborhood in Brooklyn, the city has launched a pilot program that requires developers to set-aside commercial space for local retailers in new developments that meet certain conditions — and with rents that are 30 percent below market rate.

In April 2016, the New York City council approved a major rezoning of a Brooklyn neighborhood called East New York. The new zoning rules made it easier to build larger, mixed-use buildings in the neighborhood, but with a catch: In areas that the city rezoned, it also instituted new requirements for permanent affordable housing and for active ground-floor uses along commercial corridors.

The new rules turned East New York into a centerpiece of the city’s plan to create more affordable housing. At the same time, they sparked ideas about how to ensure that new development in the neighborhood — which has a median household income that’s about one-third below that of the rest of the city — would be equitable and community-oriented.

One of those ideas is the Neighborhood Retail Preservation program, which the city is piloting in the East New York rezoning area. The program says that for any project that includes more than 10,000 square feet of ground floor retail space and that receives a city subsidy of $2 million or more, developers will be required to set aside space for local businesses at below-market rates. (To put that $2 million subsidy threshold in context, between 2014 and 2017, the New York City Housing Development Corporation spent $480 million on direct subsidies to support the city’s ten-year housing development plan).

How much space must developers set aside, and at how much of a discount? According to a June 2017 progress report [PDF], the program requires developers to reserve either 20 percent of ground floor retail space or 5,000 square feet of total space, whichever is lesser, and set initial rents at 30 percent below market-rate.

According to the progress report, the housing department (HPD) is working out which businesses will qualify as “local,” and — importantly — how developers will find them. “HPD is developing eligibility criteria for businesses that might be potential tenants for these spaces as they become available, [and] HPD will encourage developers to work with Neighborhood 360° partners in East New York to find businesses interested in becoming tenants,” the report says, referring to a city program that supports commercial revitalization projects.

So far, the pilot program is moving ahead at one site, a city-owned lot at a major intersection that’s been vacant for years. In workshops held by the city to gather input from community members, retail emerged as a priority for the site. “Participants consistently expressed the need for retail in the area,” a report on the workshops says, adding, “Workshop participants voiced a general preference for small businesses.” When the city issued its Request for Proposals (RFP) for the site, it included a requirement for ground-floor, below market-rate space for “local small retailers.”

So far, the pilot program is moving ahead at one site, a city-owned lot at a major intersection that’s been vacant for years. In workshops held by the city to gather input from community members, retail emerged as a priority for the site. “Participants consistently expressed the need for retail in the area,” a report on the workshops says, adding, “Workshop participants voiced a general preference for small businesses.” When the city issued its Request for Proposals (RFP) for the site, it included a requirement for ground-floor, below market-rate space for “local small retailers.”

In October 2017, the city announced that it had selected a proposal for the site: A building to be named Chestnut Commons, with 274 affordable apartments, and on the ground floor, a variety of spaces including a branch of Brooklyn Federal Credit Union, a satellite campus for CUNY Kingsborough Community College, and a food manufacturing kitchen incubator.

Also included in the project is ground-floor retail space that will be part of the Neighborhood Retail Preservation program. Michelle Neugebauer, the executive director of a non-profit that’s leading the development team, described the space as “affordable commercial space for neighborhood merchants.”

In the future, the city has plans to expand the program. As the progress report describes, “HPD will continue to work with developers of mixed-use affordable housing projects in the East New York rezoning area to incorporate the requirements of this pilot program into more projects.”

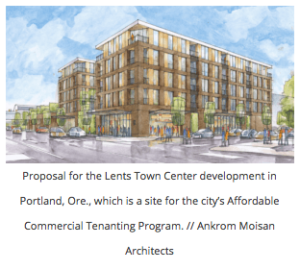

2. Portland, Ore.

Through Portland’s Affordable Commercial Tenanting Program, businesses that are owned by underrepresented groups and that meet certain neighborhood needs can lease space at three locations for below market rents.

Portland’s Lents Town Center development is a big project: 263 new housing units, 38,000 square feet of ground floor commercial space, 30,000 square feet of office, clinic, and event space, and a $54 million investment from the Portland Housing Bureau and Prosper Portland, the city’s economic development agency.

The project is notable for another reason, too. Of that commercial space, about half has been reserved for the city’s 10-month-old Affordable Commercial Tenanting Program, which offers tenants rents that are 10 percent below market-rate. Tenants may also qualify for additional incentives, like a Prosper Portland grant to help with any necessary build-out of the space.

The project is notable for another reason, too. Of that commercial space, about half has been reserved for the city’s 10-month-old Affordable Commercial Tenanting Program, which offers tenants rents that are 10 percent below market-rate. Tenants may also qualify for additional incentives, like a Prosper Portland grant to help with any necessary build-out of the space.

The Affordable Commercial Tenanting Program is part of Portland’s response to what it describes as a “recent dramatic increase in retail rents,” and related concerns about small businesses getting displaced from the city’s neighborhoods. Run by Prosper Portland, the program includes sites at Lents Town Center and at a newly opened development in the Alberta neighborhood, with plans for another site in a forthcoming project.

To select tenants for the spaces, Prosper Portland has an application process. It gives priority to businesses that are led by owners who are underrepresented in the business community, are based in Portland, and meet neighborhood needs. Among the program’s aims, the city explains, is to “advance our goal to build an equitable economy.”

3. Boulder, Colo.

In a development being built on land it owns, Boulder plans to include affordable commercial space — and to use the project as a pilot for a broader program.

In March of 2017, the city of Boulder released a Request for Proposals for a project that it described as “ambitious”: A redevelopment of an 11.2-acre site on the corner of 30th and Pearl streets, which the city had owned since 2004. The RFP outlined a vision for a development that would be mixed-use and mixed-income, with affordable housing, access to transit, and a focus on sustainability. The RFP also included something else: A call for affordable commercial space.

“Given rising rents in Boulder in recent years,” the RFP says, “there is a desire to explore models for permanently affordable commercial space which would help preserve smaller, local businesses… Proposers are encouraged to include ideas for affordable commercial space to support local businesses or non-profit organizations.”

Why affordable commercial space? The city’s interest is primarily driven by two aims, according to discussions with the Boulder Department of Planning, Housing, and Sustainability. The first is the goal of mitigating the impact that rising rents will have on Boulder’s local businesses, and along with them, on the city’s distinct character. The second is that, as the city focuses on affordable housing, it also wants to ensure that the neighborhoods around that housing are affordable too, which includes affordable retail.

The city has selected a developer for the project, and plans are moving ahead for a development with more than 300 units of housing and 21,000 square feet of affordable commercial space. The city’s currently considering questions like how to define affordable rents, and the right process for finding business tenants. Next up, it’s interested in building on the project and using it as a pilot for a program on affordable commercial space.

As these three cities are developing programs for set-asides, the idea is popping up in other places, too. In Cambridge, Mass., for instance, a group of residents recently filed a petition asking the city to require that new large developments in the Harvard Square business district set-aside half their sidewalk frontage for small stores of less than 1,250 square feet.

Meanwhile, cities are also looking at other strategies to address commercial affordability. Lawmakers in New York, for instance, are proposing a new property tax exemption for landlords who offer small and independent businesses a long-term lease with reasonable rent increases. In Seattle, the city council has funded a study to look into creating a legacy business program along the lines of San Francisco’s. And Cambridge, Mass., and Jersey City, N.J. have passed policies that restrict chain, or “formula,” businesses.

All of this new activity suggests that more cities are recognizing how important locally owned, independent businesses are to broader goals, like inclusiveness, prosperity, and sustainability. Now, they’re taking steps to create an environment that supports them.