Huffington Post: While Trump Was Dominating In Deep-Red Oklahoma, This Democrat Won A Landslide

By Zach Carter 03/09/2017 01:26 pm ET

Now Joe Maxwell is urging his party not to give up on rural America.

As precinct data rolled into his war room at the Aloft Hotel in downtown Oklahoma City last November, Joe Maxwell realized his team had a landslide on its hands.

He saw no need to delay the victory speeches, having been up since before daybreak orchestrating a statewide get-out-the-vote operation for what was expected to be a close contest. His team took the elevator to the rooftop bar, where about 50 small farmers gathered anxiously to watch the returns and, they hoped, celebrate.

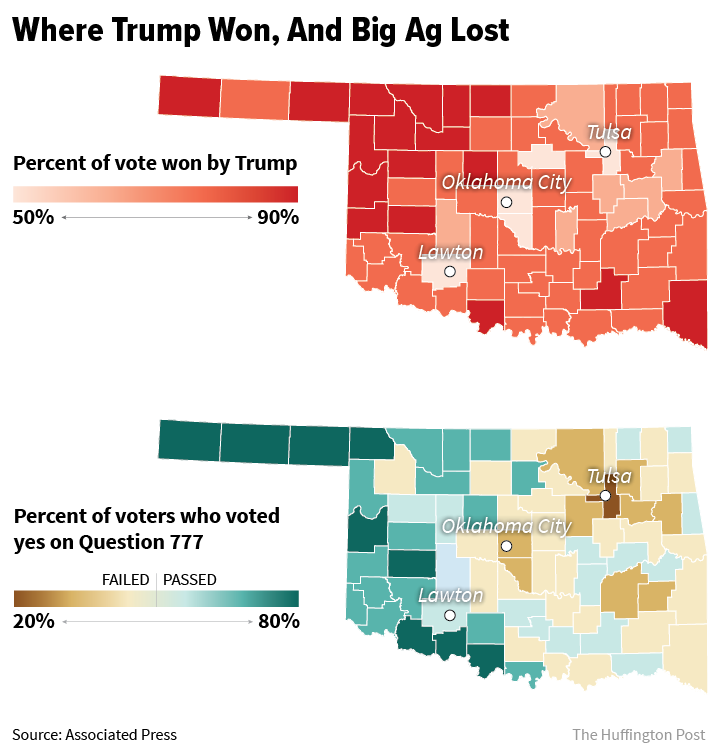

For the previous 14 months, they had battled a so-called “right to farm” ballot initiative, with Maxwell serving as “the general” (to quote his friends) of that campaign. Corporate agricultural interests in Oklahoma hoped the measure would protect factory farming from environmental, food safety and humanitarian regulations. The deep-red state’s Republican governor and every member of its all-GOP congressional delegation backed it.

In response, Maxwell, who works for the Humane Society, had helped assemble an opposition force of animal welfare activists, environmental groups, Native American tribes and family farmers. Few political strategists would have picked that coalition to overcome the influence of the state’s dominant industry. But there Maxwell was, quietly enjoying a beer as he listened to former state Attorney General Drew Edmondson (D) deliver the news of their crushing victory to a cheering audience. The “no” vote had carried every congressional district in the state and defeated Big Ag by more than 20 points.

Maxwell slapped a few backs, shook a few hands and made small talk about the view of Oklahoma City’s modest skyscrapers. The party broke up early, as people relocated to await the presidential returns. Maxwell and a few of his top deputies retreated to a bar down the street.

Not many Democrats enjoyed the evening of Nov. 8, 2016. A bit after 10 p.m., Maxwell called Barry Lynn, director of the Open Markets Program at the New America Foundation in Washington, D.C., to complain that he had no one to celebrate with.

Democrats don’t have to throw out their values. Democrats don’t even have to abandon their issues. -Joe Maxwell

Donald Trump’s triumph last November was a victory for rural and small-town voters over metropolitan enclaves, the culmination of a grim trend for Democrats that has been intensifying since the 1990s. In 1996, Bill Clinton won nearly half of America’s 3,142 counties. Sixteen years later, Barack Obama carried fewer than 700 counties and still won the election. Hillary Clinton carried just 487 and lost.

Running up the score in population centers isn’t helping much with down-ballot contests either. As culturally liberal people move away from suburban and rural communities and concentrate themselves in cities, they’ve increased the Democratic Party’s margins in already blue areas — but decreased them in swing suburban, exurban and rural districts. At the same time, Republicans have aggressively gerrymandered many previously competitive districts, redrawing them to neutralize Democratic votes. Those two factors make it extremely difficult going forward for Democrats to win the U.S. House of Representatives, where they’ve shed 69 seats since 2008, or state legislatures, where they’ve ceded more than 900 seats over the same stretch, without revitalizing their position in exurban and rural America.

After the 2016 disaster, Democrats tasked Rep. Sean Patrick Maloney (D-N.Y.) with performing an independent “autopsy” of the party’s disappointing performance in House races across the country. His team conjured a 350-variable mathematical model, studying hundreds of districts. The massive resulting equation predicts doom for Democrats in districts with few college-educated voters, but sees promise in wealthier, diversifying suburbs. It suggests a strategy that effectively writes off all of rural America.

“They’re just wrong,” Maxwell said. “They can’t do that, and they don’t have to.”

Maxwell’s brand of politics looks beyond the poll-tested analytics that dominate Washington. Even the best mathematical models — tools like Maloney’s current project — are only useful at a particular snapshot in time. They treat voters as static data points, rather than human beings capable of changing their minds. A model might focus on the number of Democrats registered in a district to predict the party’s performance in an upcoming race. But models can’t explain how to create more Democrats in that district.

Maxwell won where Democrats weren’t even playing, in a state where Trump carried every single voting precinct. When he convinced the Humane Society to get involved against the right-to-farm measure in 2015, independent polling showed his side trailing 64 percent to 15 percent.

His decision to fight and battle plan reveal a possible path for the Democratic Party out of the political wilderness and back to electoral relevance. But taking it would require rejecting the political strategy that Democratic leaders are now honing in Washington.

“Democrats don’t have to throw out their values,” Maxwell insists. “Democrats don’t even have to abandon their issues. It’s about how you frame it. It’s about connecting with people and showing them how your ideas fit with their values.”

Maxwell, 59, and his brother Steve run a farm in northeastern Missouri, just outside the town of Mexico, with a population of roughly 11,000. They’re fourth-generation hog farmers, and politics wasn’t a focus growing up. After stints in the Army and the U.S. Postal Service, Maxwell returned to the family business in the late 1970s, just in time for Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker’s crusade against inflation.

The Fed’s ruthless interest rate hikes didn’t just bring down prices; they devastated small farmers, sparking a great wave of farm foreclosures across the country. When the farms failed, so did the local community banks that had loaned them money. And when the banks collapsed, so did other local businesses that relied on them for credit. Rural America was ravaged. Farmers rode tractors into Washington to snarl traffic in protest, and Maxwell decided to go into politics.

“That’s when I realized that government actions pick winners and losers,” he said. “And they’d decided that my industry was a loser.”

Maxwell began volunteering for Rep. Harold Volkmer (D-Mo.), and by 1986 he was working on the presidential campaign of Rep. Dick Gephardt (D-Mo.). He helped Gephardt organize his ultimately unsuccessful opposition to the North American Free Trade Agreement before striking out on his own. Maxwell won election first to the Missouri legislature and then as the state’s lieutenant governor in 2000 — another year when his win bucked a bad national trend for Democrats.

“I’m pretty good at getting up and giving a line to people on the stump,” said Wes Shoemyer, a former Missouri state senator. “Me personally, I’m just a good ol’ boy, not too sophisticated. Joe, he’s a sophisticated good ol’ boy. And that’s something the Democrats lost.”

Statewide Democratic campaigns in Missouri typically set up shop in Democratic-friendly cities like St. Louis or Kansas City. Maxwell ran his campaign for lieutenant governor from his hometown, which meant he didn’t have to sit through city traffic every time he set out to stump in rural Missouri. Working adjacent to a farm did have its drawbacks, however.

“We were in an at-times flea-infested office,” recalled Tricia Workman, a Missouri-based lobbyist who managed the campaign. “I probably paid to exterminate them myself. But he campaigned on agriculture, which is the state’s biggest industry.”

“And he campaigned on health care, the working class, the middle class — everybody gets a quality education,” she said. “And we won on that. … Democrats used to be a lot more popular in the state.”

![Michael Cali for The Huffington Post To win over voters, Maxwell argues, “you have to go be where they are ... and [show] them that you are like them, that you share their values.”](https://news.mikecallicrate.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/58bb84ab1a00003400f41a14.jpeg)

Michael Cali for The Huffington Post

To win over voters, Maxwell argues, “you have to go be where they are … and [show] them that you are like them, that you share their values.”

Maxwell still speaks lovingly of “Jeffersonian democracy” and hails Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. There’s a harmony between his attacks on corporate farm interests and the rhetorical assaults from Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) against the 1 percent. But Maxwell and his allies aren’t selling democratic socialism.

“We don’t want government subsidies,” said Fred Stokes, a Maxwell collaborator who founded the Organization for Competitive Markets, which advocates for small farms against big producers like Tyson, Perdue and Smithfield. “We just want the game to be fair. Apply the damn antitrust laws and it’ll work. Teddy Roosevelt had this figured out 100 years ago. I don’t know why it’s so damn hard for people to understand.”

The work that Maxwell and the Humane Society of the United States are doing in rural America could serve as a foundation for further outreach. The Humane Society’s battles against factory farms, puppy mills, research labs and other places that abuse animals are nonpartisan. Its advocates are Democratic and Republican alike, and its explicit political organ, the Humane Society Legislative Fund, supports candidates from both parties. But many of the alliances it has built look like the nascent stage of a new rural liberalism.

In 2010, the group’s president, Wayne Pacelle, was in Jefferson City, Missouri, to lobby in favor of a state ballot proposal to crack down on puppy mills. He ran into Maxwell at the statehouse. “It was a pure case of serendipity,” Pacelle said.

Maxwell had backed a bill to ban cockfighting during his time in the state legislature, and he’d gone after Big Ag for animal cruelty before. Pacelle hired him to direct the Humane Society’s rural outreach program. Connecting with farmers as an animal welfare advocate requires overcoming some significant cultural barriers. A lot of farmers see the Humane Society’s efforts against animal cruelty as a Trojan horse — the first step in a project that ends with forced vegetarianism and the elimination of all animal agriculture.

“What people may not realize about places like Oklahoma is, yes, there is a huge agricultural industry, mostly wheat and cattle,” said F. Bailey Norwood, an agricultural economist at Oklahoma State University. “But ag is also a very popular hobby. … For a lot of kids growing up, their hobby was showing cattle or showing hogs. They show farm animals the way other people show dogs. So even when people don’t farm for a living, there’s a real connection with farm culture.”

“With my students, there’s a lot of us-versus-them mentality,” he said. “Us, the good Oklahomans who raise our animals right, and them, these crazy animal rights activists and environmentalists from California who wanna tell us what to do.”

Stokes, the small-farmers advocate, acknowledged that Maxwell’s association with the Humane Society is a significant cultural barrier.

“All of us catch a lot of hell for that,” Stokes said. “They’ve been conditioned by Farm Bureau and everyone else over the years to think badly about the Humane Society, when they’ve been very good to us and asked for absolutely nothing in return.” (The American Farm Bureau Federation is a century-old organization that advocates for the agricultural industry, but tends to represent the goals of Big Ag.)

But there is a common interest between family farmers — who are routinely undercut by the market power of big meat-packing companies — and animal welfare advocates — who want to end brutal factory farming techniques that small farms, by definition, don’t deploy. And Maxwell is getting results. Back in 2002, when he was still lieutenant governor, the Humane Society helped pass an anti-cockfighting ballot initiative in Oklahoma. But it did so by getting strong turnout in Tulsa and Oklahoma City. Initiative supporters carried only 11 of the state’s 77 counties. On the 2016 right-to-farm question, Maxwell’s side won 37.

“You have to go meet them,” said Maxwell, referring to voters. “You have to go be where they are. It’s about who they are and showing them that you are like them, that you share their values. If you’re in their coffee shop or barber shop or their synagogue or their church — if you’re there, then they feel comfortable to express themselves. You can’t do that in a poll.”

The Humane Society’s success at state-level politics has earned it a lot of enemies. Major food and agriculture companies hired PR guru and super-lobbyist Rick Berman to target the Humane Society with a complex propaganda operation. Berman is behind both the think-tank-sounding Center for Consumer Freedom and the blog HumaneWatch.org, which has visually caricatured Maxwell as a puppet and falsely smeared him as an animal torturer.

“HSUS is a vegan organization — they don’t want people to ultimately eat meat,” Will Coggin, research director for the Center for Consumer Freedom, claimed. “If they want to be like PETA, they should be as honest as PETA is about their agenda.”

This charge is, of course, impossible to square with Maxwell’s career as a hog farmer.

“I represent Monsanto, which Joe hates, but I still have the absolute biggest respect for him that I possibly could, as a human being and as a politician,” said Workman, his former campaign manager who has since returned to lobbying.

While Maxwell is notching victories now, any broader Democratic Party strategy for rural America would take time to pay off. But he didn’t win the first one either.

In 2014, when Maxwell decided to fight a right-to-farm ballot initiative in Missouri, Big Ag had a 35-point lead. Maxwell’s side ended up losing the vote by a whisper-thin 0.2 percent. Former Oklahoma state Sen. Paul Muegge (D) took note. When a similar plan was introduced in Oklahoma, he called Maxwell and urged him to join the opposition campaign, which was headed by Cynthia Armstrong, the Humane Society’s top operative in the state.

Right-to-farm measures come with a sympathetic label, but they benefit big agricultural conglomerates, giving them legal protections that help elbow smaller producers out of the market. The Oklahoma nitiative would have amended the state constitution to make it all but impossible for the state government to regulate farming technology, either by statute or agency rules. Unless the government could demonstrate “a compelling state interest” — an extremely high standard of legal scrutiny that also applies, for example, to restrictions on voting rights — new farming rules would be forbidden. Even if the state could show a compelling interest, corporate agriculture could have used the right-to-farm law to tie up new standards in court for years.

Maxwell was tasked with everything from writing speeches to pitching farmers face-to-face on the “no” campaign.

“The farm community is so much faith-based, I thought the idea of stewardship could really be a powerful message,” Maxwell said. “Stewardship of the animals, stewardship of the land.”

He also saw an opening on environmental concerns, which are paramount in many portions of the state. The Illinois River, Lake Tenkiller and other waterways in eastern Oklahoma have been polluted for years, due primarily to chicken waste runoff from big poultry farms. Eastern counties broke hard for Maxwell’s side on election night.

“I think Joe’s an amazing person,” said Mike Callicrate, a Kansas cattle rancher who serves on the board of the Organization for Competitive Markets. “And it’s going to be his work and his coalition-building that will save family farming and get people back to the land. That win in Oklahoma might be the turning point.”

Victory builds confidence. Maxwell spent this past New Year’s Eve in his hometown with brother Steve and former lawmaker Shoemyer. In deep-red northeastern Missouri, one of the bars on the town square displayed a sign declaring that anyone who had voted for Hillary Clinton would not be served.

Maxwell’s crew took the hint and started their evening on the other side of the square. After a few rounds, his drinking buddies looked up to see him walking toward the anti-Clinton sign.

Maxwell walked in, slammed his hand down on the bar and said, “I voted for Hillary Clinton and I want a beer!”

He got his beer.