Cory Booker: A handful of companies make most of our food. We need to end big food mergers

"If we will not endure a king as a political power, we should not endure a king over the production, transportation and sale of any of the necessities of life."

Cory Booker: A handful of companies make most of our food. We need to end big food mergers

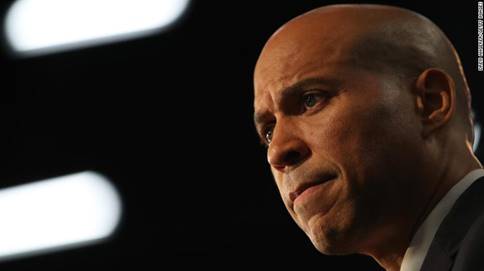

By Cory Booker for CNN Business Perspectives

Updated 8:08 AM ET, Thu July 25, 2019

Cory Booker is a US senator from New Jersey and Democratic candidate for president. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own.

On December 4, 1889, US Senator John Sherman of Ohio introduced the Sherman Antitrust Act into the 51st Congress of the United States. Three months later, he took to the Senate floor to defend his proposal, which would eventually become law, and form the linchpin of the American antitrust system.

Of all the problems upending the social and economic order of the United States, he said, "none is more threatening than the inequality of condition, of wealth and opportunity that has grown within a single generation out of the concentration of capital into vast combinations to control production and trade and to break down competition."

Sherman’s words were spoken 129 years ago, but they would fit seamlessly into today’s political and economic reality, where fair and open markets have been replaced by just a few giant corporations in sector after sector of our modern economy.

Nowhere is this more clear than in our agriculture sector and food system. Four companies — Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus — control as much as 90% of the global grain market, and three companies — Bayer-Monsanto, Corteva Agriscience, ChemChina-Syngenta — now control over 60% of the world’s commodity crop seeds. In the past three decades, the top four steer and heifer packers in our country have expanded their market share to 85%.

These excessive levels of concentration and market power are devastating our independent family farmers and ranchers and hollowing out the rural communities in which they live. Farmers and ranchers are being forced to sell into even more concentrated marketplaces that unfairly reduce the prices they receive for their crops and livestock, and unfairly increase the cost of labor, machinery, livestock, seeds and chemicals.

In 1950, a farmer would get 41 cents from every retail dollar for the products he sold; today that portion has plummeted to 15 cents.

Meanwhile, net farm income for US farmers has fallen by half in just five years.

Struggling to survive, many farmers resort to becoming "contract growers" for massive, vertically integrated multinational corporations. Under this model, the integrator — think JBS USA, Tyson Foods or Smithfield Foods — owns the animals and the farmer gets paid to raise them on their property.

But the farmers have to absorb all the costs and all the risks, and are forced to accept whatever price the corporate integrator pays. Today, 71% of contract poultry growers who depend on the income from their poultry contracts live at or below the federal poverty level, often with massive amounts of debt. It’s modern-day sharecropping.

I’ve heard these stories firsthand, both from farmers in New Jersey and farmers I met with last year in Missouri, Kansas and Illinois. Sitting around kitchen tables, I heard story after story about how farmers were struggling to survive because of the big monopolies they faced at every turn.

This is not the agricultural economy envisioned by our laws. The Sherman Antitrust Act, along with the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 and the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921, provided strong tools for antitrust enforcement in order to protect free and open markets.

More Markets & Economy Perspectives

The best way to keep powerful companies in check

Where Trump went wrong in the US-China trade war

The US-China trade war hurts American families

Unfortunately, for the past three decades, our antitrust agencies have irresponsibly abdicated their role in enforcing antitrust law. The Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission have departed significantly from their congressional mandates and have taken a misguidedly narrow approach to their enforcement efforts.

In the absence of such enforcement, I’m renewing my call for a moratorium on big ag mergers by reintroducing the Food and Agribusiness Merger Moratorium and Antitrust Review Act.

Originally introduced last year in the previous Congress, the bill targets large agribusiness, food and beverage manufacturing, and grocery retail mergers and acquisitions. It would immediately halt the largest, most consequential acquisitions and mergers in the food and agriculture sector and give Congress an opportunity to update our antitrust laws in order to better protect America’s farmers, workers, consumers and rural communities, who are being harmed by the ever-increasing levels of corporate concentration.

In addition to the moratorium, the bill would set up a commission to study how to strengthen antitrust oversight of the farm and food sectors and publish recommended improvements to merger enforcement and antitrust rules.

We must restore competition to the marketplace so our farmers and ranchers can once again have the opportunity to share in the prosperity that open, transparent and fair markets provide. And that means that Congress must pass comprehensive legislation ensuring our antitrust laws are tailored to today’s markets, and federal agencies must once again aggressively enforce our existing antitrust laws.

As Sherman proclaimed days before his namesake antitrust bill would pass the Senate in 1890, "If we will not endure a king as a political power, we should not endure a king over the production, transportation and sale of any of the necessities of life."

I couldn’t agree more.