Civil Eats: No-Till Farmers’ Push for Healthy Soils Ignites a Movement in the Plains

By Twilight Greenaway | FARMING, Rural Environment and Agriculture Project | 02.13.18

No-till farming started as a way to keep costs down for conventional farmers in danger of losing their land. Now it has become a subculture and a way of life for outsider farmers all over rural America.

Editors’ Note: Today, we introduce our year-long reporting series on rural America, the Rural Environment and Agriculture Project (REAP).

Jimmy Emmons isn’t the kind of farmer you might expect to talk for over an hour about rebuilding an ecosystem. And yet, on a recent Wednesday in January, before a group of around 800 farmers, that’s exactly what he did.

After walking onstage at the Hyatt in Wichita, Kansas to upbeat country music and stage lights reminiscent of a Garth Brooks concert, Emmons declared himself a recovering tillage addict. Then he got down to business detailing the way he and his wife Ginger have re-built the soil on their 2,000-acre, third-generation Oklahoma farm.

A high point of the presentation came when the 50-something farmer—who now raises cattle and grows alfalfa, wheat, and canola along with myriad cover crops—described a deep trench he’d dug in one of his fields for the purposes of showing some out of town visitors a subterranean cross-section of his soil. After it rained, Emmons walked down into the trench with his camera phone, and traced the way water had infiltrated the soil. Along the way, the Emmons on stage and the Emmons behind the camera became a kind of chorus of enthusiasm, pointing out earthworm activity, a root that had grown over two-and-a-half feet down, and the layer of dark, carbon-rich soil.

“It was just amazing,” said Emmons in an energetic southern drawl. The water had seeped down over five feet. And the other farmers in the room—a collection of livestock, grain and legume producers mainly from Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, and the Dakotas, as well as several Canadian provinces who had gathered for the 22nd annual No-till on the Plains conference—nodded their heads in a collective amen.

Most had travelled for hours to hear Emmons and others like him share their soil secrets, their battle scars, and their reasons to hope. And they knew that getting rainwater to truly soak into farmland—instead of hitting dry, dead soil, soaking an inch or two down, and then running laterally off—is a lost art.

The previous morning, the controversial grazing guru Allan Savory had stood on the same stage before the enthusiastic crowd and described the enormous quantity of spent, lifeless soil that erodes into the ocean every year in terms of train cars. “A train load of soil 116 miles long leaves the country every day,” said Savory, quoting the Natural Resources Conservation Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Or to put it another way, erosion accounts for the loss of around 1.7 billion tons of farmland around the world very year. As that soil escapes, so does an abundance of nitrogen and other nutrients that are slowly killing vast parts of our oceans and lakes. And as agricultural soil dies and disperses, it also releases greenhouse gases like nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide.

As the world begins to zero in on the need to bring this soil back to life—as a solution to drought, nitrogen pollution, climate change, and more—farmers like Emmons and others practicing no-till in the middle of the country could play a key role. As they reshape their operations with a focus on things like earthworms and water filtration, and practice a suite of other approaches that fit loosely under the umbrella of “regenerative agriculture,” these farmers are stepping out of the ag mainstream. And while most no-till farmers see organic agriculture as inherently disruptive to the soil, they also have a great deal in common with many of the smaller-scale farmers that are popular with today’s coastal consumers.

These two groups of farmers don’t use the same language to describe what they’re doing (you’re unlikely to hear words like “sustainable” or “climate change” among the no-till set, for instance), but it’s clear that both groups are motivated by the opportunity to be responsible stewards of the land while exploring creative solutions to the status quo. And many no-till farmers are also just as skeptical as their organic counterparts are of the large seed and fertilizer companies they see as running their neighbors’ lives (and controlling their finances).

With Every End Comes a New Beginning

No-till farming has been around for more than half a century, ever since herbicides and precision planting tools allowed farmers to plant crops directly into the soil without disturbing it. But because tilling—or breaking up the soil—is primarily a means to control weeds, farmers who practice no-till have often relied heavily on herbicides to manage weeds instead. For this reason, it has traditionally found a home among conventional farmers looking for a way to improve yields or cut costs—although some no-tillers reject the term “conventional.”

But over the last decade or so, no-till has also become a kind of farming subculture—a world in and of itself. And, as the farmers who gathered in Wichita see it, putting an end to tilling the soil is often just the beginning of a whole range of practices that include growing cover crops, managed grazing, and diversification, i.e., literally increasing the number of cash crops in their rotations.

“No-till without cover crops and crop diversity is still an incomplete system,” Emmons told the crowd.

Together, however, these approaches have the ability to bring back living fungal ecosystems in the soil, retain water and organic matter, and sequester carbon. The farmers who practice them are also eligible for conservation funding from the USDA via the farm bill, and yet they are likely to see a reduction in the amount of available funds in this year’s smaller-than-average bill.

Many of these practices have also made modest gains in popularity recently. According to the USDA’s latest data, by 2010-11, no-till farming had grown to the point where roughly 40 percent of the corn, soybean, wheat, and cotton grown per year in the U.S. used either no-till or a half-step technique called strip-tilling. That works out to around 89 million acres per year. And while it’s unclear just how many of these farmers see no-till as a bridge to other practices—and therefore a way to cut down on the quantities of synthetic herbicides and fertilizers—it’s clear that the path forward is there for those who do.

Photo of dark, carbon-rich soil courtesy of North Central Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education.

“Those who are truly committed to regenerative ag are trying to use plants in place of [fertilizer and herbicides],” says Steve Swaffer, executive director of No–till on the Plains, the nonprofit that hosts the annual conference. “As your soils heal and go back to a more natural state,” he says, most successful farmers are able to “wean themselves off” chemicals. But he adds that most “haven’t eliminated [herbicides, pesticides, and synthetic fertilizers] from their toolbox,” entirely even if they see them as last-resort options.

“You can’t quit [synthetic fertilizer and herbicides] cold-turkey,” said Adam Chappell, a fourth-generation farmer from Arkansas who practices no-till and plants cover crops on over 8,000 of the 9,000 acres he farms with his brother. Now that he’s several years into the practice, however, he said, “I don’t need seed treatments for my cotton anymore. I’ve taken the insecticide off my soybeans. I’m working toward getting rid of fungicide … I’m hoping that eventually my soil will be healthy enough that I can get rid of all of it all together.”

Nearly all the farmers who spoke at the conference had similar stories. And while many of the environmental benefits were left implied, the financial benefits were right up front. Emmons reported cutting fuel costs by two-thirds and fertilizer costs by half. Derek Axten, a grain and pulse farmer from southern Saskatchewan, described a major reduction in fungicide use for the high-value chickpeas he grows there. “I used one application while my neighbors used five,” he told the audience. “That works out to about $100 an acre.”

For today’s farmers, many of whom are squeezed financially at every turn, this ability to spend less on inputs is hugely compelling. “It’s not always how much money you make, it’s how much you keep,” Axton told the crowd.

Since this approach requires gradual, system-level changes, however, Emmons underscored, “the first year is going to be crappy. The cover crops aren’t going to work as well as you want and you’ll want to give up. But if you can make it three to four years, you’ll start seeing fungal dominance, more diversity of living organisms in the soil, and more biomass in the system.”

Tension with Organic

There was a resounding disdain at the conference for large organic operations, which many no-till farmers see as “ruining the soil” by tilling it.

Jonathan Lungren, an agroecologist and entomologist who left a job with the USDA in 2015 after filing a whistleblower suit alleging the agency had suppressed his research on bee health and pesticides to start a farm and nonprofit science lab for independent research in North Dakota, is an interesting example of this perspective.

After meeting no-till veteran and minor farm celebrity Gabe Brown and cover crop expert Gail Fuller, Lungren says he was convinced to try their approach. “Some farmers are way ahead of the science when it comes to this stuff,” he said. He contends that, “Insecticides are an addiction. The more you use, the more you need,” and advocated for “changing the whole system, rather than trying to make a broken system work.”

And yet, his disdain for certified organic farms was palpable. “I’ve been on organic farms in California and I wouldn’t eat that food,” he said. “The soil is dust!”

Of course, not all organic farms are the same and while most do practice tillage, they also build fertility slowly using compost, rather than synthetic fertilizer—a fact that some research says makes their practices inherently better for the soil than most conventional systems. And many organic producers also rely on cover crops, green manure, and crop diversity to retain carbon and organic matter in the soil. For instance, a 2017 study from Northwestern University found that soils from organic farms had 13 percent more soil organic matter (SOM) and 26 percent more potential for long-term carbon storage than soils from conventional farms

But Kristine Nichols, former chief scientist for the Rodale Institute—one of the only locations where researchers have long-running plots that combine no-till with organic practices—says that the gradual breakdown to fungal communities in the soil over time in many organic systems can be a serious problem.

“Tilling can start to erode the diversity of the fungi in the soil over time. So you’re going to start getting the loss of certain keystone organisms for providing amino acids and antioxidants that can be very important for human health,” said Nichols. While at Rodale, Nichols worked with researchers at Penn State University to look at an antioxidant and amino acid called ergothioneine, which is produced by soil fungi. They saw a very strong relationship between both the concentration and frequency of tillage and loss off ergothioneine.

As scientists begin to get a firmer grasp on the human microbiome and its relationship with microbial communities in the soil, Nichole believes, “it’s going to start putting more pressure on the organic community to reduce tillage.”

Nichols, who worked with no-till farmers in Nebraska for a decade before going to Rodale, says that while organic farmers tend to see any use of herbicides as “the ultimate evil,” the no-till set feel similarly about tillage. In the same way that no-till farmers are often told to use herbicides only when no other solution is available to them, Nichols likes to challenge organic farmers to see tillage as the choice of last resort.

Steve Swaffer also acknowledged that that sweeping generalization about soil health can be hard to make. “It’s all about management, right? And it’s a human being who makes the decisions about how a farm is managed,” he explained by phone after the event.

“I think that the organic producers have been bastardized somewhat because of the large production and people capitalizing on the premiums that are available,” he said. “I’ve been on these farms where it’s a monoculture of lettuce or spinach and it certainly meets the organic standard, but the dirt that’s being used as a growing medium has no life in it. And yet those people are able to capture those premiums.” Meanwhile, he added, many of the farmers he works with aren’t able to sell the food they grow outside the commodity market. “So I think there’s probably some resentment,” he said.

That feeling is compounded by the fact that many of the farmers who gathered in Wichita are often ostracized in their own communities for stepping outside the expected rules of conventional agriculture.

Soybeans coming up in a rye cover crop. Photo by Lander Legge for USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS).

Even Jimmy Emmons, who seems about as self-assured as a farmer can be, acknowledged that he doesn’t even go to his local coffee shop anymore. If he did, he’d hear disapproval from his fellow farmers for doing things like planting his wheat directly into a living stand of plant residue without tilling or grazing his animals on cover crops.

On one panel at the conference, for instance, Adam Chappell responded to a comment made about the science of monoculture by saying, “There is no scientific evidence of the benefit of monoculture, but there is plenty of propaganda. The salesmen tell me constantly that I’m stupid, or that I’ll go broke” because he’s using fewer inputs.

Tuning out those messages, he added, has become a lot easier thanks to the network of other no-till farmers he stays in touch with online—Twitter and YouTube are popular platforms for sharing photos, observations, and videos of one another’s farms—and at conferences like No-till in the Plains.

Reaching Consumers

In some ways, the fact that this approach to farming is based on profiting by cutting costs has liberated the “soil health movement” from the need to make a premium by differentiating in the marketplace. And yet several groups are currently working to do just that through potential certification schemes for regenerative agriculture, making a label likely in the near future.

And because consumers are more likely to spend with their health in mind than the health of the environment, the success of such a label may rely, at least in part, on proving what many no-till and regenerative farmers say they’ve seen anecdotally: that healthier soil leads to more nutrient-dense food. And several of the scientists present in Wichita, like Nichols and Jill Clapperton, farmer and founder of Rhizoterra, hope to help move that research forward.

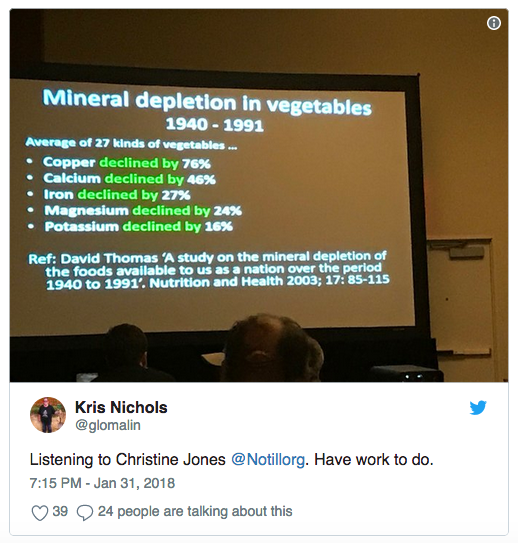

At the conference, Australian soil ecologist Christine Jones pointed to research that looked at 27 kinds of vegetables and found that since 1940, the amount of copper present in the food had declined by 76 percent, while calcium had declined by 46 percent, iron by 27 percent, magnesium by 24 percent, and potassium by 16 percent. She and others believe that depleted soil is the culprit. But rather than being deficient in minerals, argued Jones, today’s soils are often deficient in the microbes necessary to help plants access those minerals.

Nichols points to ongoing research at The University of Massachusetts, Johns Hopkins, and the University of California at Davis aimed at determining the links between soil health and nutritive content in food. And she says some of the preliminary research she has seen suggests that improved soil health could point toward solutions to the obesity crisis as well.

The diluted nutrient content in our food, says Nichols, “basically drives our bodies to have to consume more. Our gut microbiome essentially signals to our brain that it’s starving, and says, ‘eat more food.’”

She hopes that the organic and no-till communities—which are both relatively small on their own—can work together to begin to find solutions. If that doesn’t work, she says, a broader goal of saving soil could inspire unity.

“Organic farmers, conventional farmers, no-till farmers—everyone is seeing soil leaving their farms,’ says Nichols. “Reducing the amount of tillage you’re doing is a very significant way to stop that from occurring.”