Civil Eats: I am the Daughter of a Conventional Farmer—and a Sustainable Ag Advocate

by Ash Bruxvoort | Commentary, Rural Environment and Agriculture Project | 05.07.18

‘I grew up on the urban-rural divide. I live it every day. And I’ve come to see how we collectively suffer when we see it as a debate, rather than an opportunity for growth and understanding.’

To most people, my dad is a headline, a stereotype. He’s a 62-year old conventional corn and soy farmer living in Iowa, a Trump supporter, and—some assume—a backward, ignorant white man. But to me, he’s a kind and reliable man trying to make the best decisions for his family and himself.

I grew up on a nine-mile stretch of road east of Des Moines, in a town called Mitchellville. My parents shuttled me back and forth on this road between our fourth-generation farm and my grandparents’ farm. Like most farms, we required off-farm income and my mom worked in Des Moines for DuPont Pioneer and later Wells Fargo for our health insurance.

I watched my parents’ ecstasy through high corn and soy markets and despair through low markets. My parents were married at the beginning of the 1980s farm crisis, and while I grew up during many of the “good years,” the fear of the next crisis still hovers over my family.

Over the years, my status as a Midwest farmer’s daughter has been met with a variety of reactions. In liberal, urban spaces, I am asked incessant questions about pesticides and meat consumption by the same people who are concerned about subsidies and how much money they think my father makes while “polluting the earth.” On the coasts, the most common reaction is, “I’m sorry.”

In rural and suburban Midwestern spaces folks are often curious about how many acres my father works. Does he have any livestock? “I don’t really know,” I was coached to respond. An exact number of acres might translate into an understanding of net worth, which my father told me was none of their business. And in his eyes, the less I understood about farming, the easier it would be for me to fit into the professional world.

My father encouraged me to pursue a stable career in corporate America. Instead, I started working for conservation and agriculture nonprofits. I wanted to understand the food system from as many perspectives as possible. At first, my views on the best ways to change the food system came directly from the coastal food movement: support local, organic farmers; transition conventional acres to organic; save the bees.

All good things, but when I tried to talk to my father about them I was always asked about the financial viability of these operations. As my work took me deeper into the food system and I worked with a wide range of farmers, I realized that many of the farmers doing the “better” farming were also struggling.

After seeing how broken the system is, I have been compelled to want to change it. Like many of the other farmer’s daughters I’ve met, my experiences drive me to want to create a new and better vision for the food system. But that doesn’t mean I think we should leave farmers like my father behind.

Those struggles include a high percentage of rural households reliant on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), lack of medical care and closing hospitals, and increasing rates of opioid addiction. All of these issues need to be addressed, and as a farmer’s daughter, I know that they are symptoms of a larger wound that stems from living at the mercy of a highly consolidated, volatile set of markets that prioritize profit over people.

As more farmland changes hands and family farmers are pushed off the land, farmer’s daughters could play a critical role in shaping our food system and shifting the larger narrative about what we should prioritize within that system. As we’ve watched our families and neighbors struggle and thrive, we’ve seen the holes in the food system and have the tools and transformational stories to bridge the divisive conversation happening today.

A Unique Role

The farmer’s daughters I’ve known were less likely to be encouraged to stay on the farm than their male counterparts. And for that reason, they’ve been more likely to pursue educational and career paths that bring them to urban communities. Once they are integrated into the urban or corporate world, they often find themselves trying to explain rural life to people who have never stepped foot on a farm. And many of them find themselves drawn to return.

“I was never asked to drive a tractor or help with the real farm chores. I was never taught about the business side of things, no one ever asked if I saw myself farming,” says Wendy Johnson, an Iowa organic farmer who returned to her family’s land after spending over a decade working as a photo stylist in Minnesota, California, Japan, and Brazil. Over the past 8 years, she has rented land from her family and has slowly worked toward her vision of farming with more sustainable practices, including more cover crops, continuous no-till, and small-scale livestock production.

“I saw the farm as fun and pretty,” says Johnson of her childhood. She has learned the business side as an adult, and has learned many of the hard realities of farming. But re-creating the beautiful life she caught a glimpse of as a child has always been part of what drives her.

For the first couple of years, Johnson shared stories about what she was doing with friends in California, friends who had never been on a farm. And she found herself trying to bridge two very different worlds.

And although she had a good relationship with her family, Johnson has also been met with the kind of hard realities other farmer’s daughters have faced. Most of today’s farm communities are aging and young people are often scarce. In many places, women who take up farming might not be treated with the respect as their male counterparts. And if their brothers or cousins have taken over the family farm, these women might be less likely to have access to land.

Some, like Lauren Rudersdorf from Brodhead, Wisconsin, have to strike out on their own. Like me, she watched her parents attach their personal wealth to market fluctuations on their diversified family farm. Her parents worked off-farm for the majority of their income and by the time they gave up the farm they resented the life they had built.

“I saw the brokenness from the inside, the lack of a balanced life,” she wrote recently in a post on the Midwest Environmental Advocates blog. “I saw them doing something they loved and taking immense pride in it, but feeling like little more than a cog in a system… It broke my heart and I knew there had to be [something] better.”

In 2013, Rudersdorf started Raleigh’s Hillside Farm, a certified-organic, community supported agriculture (CSA) farm south of Madison, Wisconsin with her husband, Kyle. She also works off the farm for a nonprofit environmental law center. Her parents help with the farm, and she said that they were surprised and proud when Lauren and Kyle made a profit in their second year.

Translating

Advancing an inclusive vision of food and farming isn’t easy—especially when most people, even in agricultural states like Iowa, seem to know very little about the realities farmers and rural Americans face.

Rudersdorf hopes to help turn the tide by sharing recipes and stories about farm life on her blog, where she educates her customers about vegetable production and farm finances. Like many farmer’s daughters, she is often in the role of translating farm life to a larger audience.

Kayla Koether has also had experience translating rural issues for a larger audience. She’s a farmer’s daughter running for Iowa House District 55. Koether worked with her father on their livestock farm and studied international agriculture and rural development at Grinnell College.

When Koether brought her city-born college friends to the farm she made a point to show them not only her family’s livestock operation, but also other farms in the area so that they could gain a larger understanding of farming in her area.

“Sometimes you end up translating agriculture to people who don’t fully understand it,” said Koether. “It’s not that they don’t want to understand, it’s that they haven’t had the opportunity to try.”

In order to be a translator you need to have access to audiences on both sides of the divide. And those of us who do, often feel compelled to help urban consumers and policy makers understand the struggles of rural America. Because while most rural folks are forced to go to the cities nearby for basic necessities, urban folks can go years without interacting with their rural neighbors.

In college, when I submitted an essay about my experiences as a teenager in the punk scene in Des Moines, my writing instructor said, “I thought you grew up in the country?”

“Yes,” I said. “Both of these things are true.”

Each family has its own complicated dynamics and every farmer’s daughter experiences the farm differently. But it is an undeniably unique way to grow up.

“I came of age right around the 1980s in Iowa, during the farm crisis,” Carolyn Van Meter told me over the phone. “There was no way anyone was going to stay in Iowa. Even if we had planned for careers that weren’t related to agriculture, there just weren’t many job openings. We all left.”

Van Meter ended up in Jupiter, Florida, where she owns a tax preparation, estate, and financial planning business. At age 61, Van Meter has owned Iowa farmland for five years and is starting to see her childhood peers begin to inherit and buy into their family farms too.

When Van Meter confirmed that she would inherit land from her family, she looked for resources. She had discussed the farm transition with her parents in a fairly open manner, but she found there were still things she didn’t understand. In December, she became a certified International Farm Transition Network (IFTN) coordinator, in an effort to help farmers in the process of transitioning in and out or farming. As a farmer’s daughter, she can understand the nuances of farm transition such as grief and ancestral ties. She knows that a farm is not only a home, but a livelihood, and a way of life.

Compassion & Empathy

Farmer’s daughters’ ability to occupy two spaces at once also shows up in political discussions.

I recently had a conversation with a young man in a bar in Des Moines. He was a lawyer and, like me, a Bernie Sanders supporter. He said that he didn’t like giving Trump supporters “a pass,” and told me he’d read many profiles about people in Trump country. He felt that he understood them and their struggles but could not excuse their racism. I told him that there’s a big difference between reading a profile about someone in the Washington Post and actively having conversations with people who don’t agree with you. And it’s true—that’s the only way change will happen.

As a queer woman who grew up right on the divide, I am acutely aware of the stereotypes we place on each other. It is far easier to fit someone into a box like “Trump-supporting, racist farmer” than to understand that person as a human. We talk about the urban-rural divide as if it is a debate, rather than an opportunity for growth and understanding. As people sit on both sides of the divide and assume their own views are correct, we collectively suffer.

No one has taught me more about unconventional love than my dad. We disagree all the time and I’m grateful for it.

I lived with my parents during the last presidential election, and he and I watched every debate together. There was anger, frustration, and yelling. There was also laughter and heartfelt conversation. We discussed how the food system doesn’t support the workers producing the food, and how he is essentially a cog in a system, and I listened to his heartbreaking response: “I don’t know how to do it another way. I am too old.”

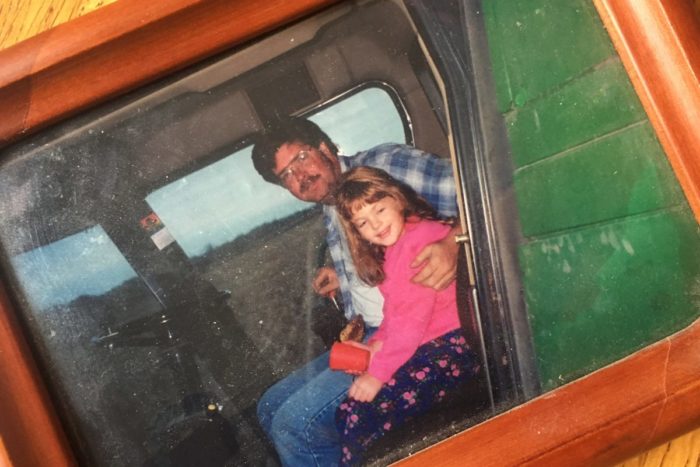

I keep a photograph of my father and I on my desk. In it, we’re sitting in the combine and I’m probably six years old. My dad is wearing a blue flannel shirt and has a mustache. Shania Twain was probably playing on the radio and I was singing and dancing next to my dad in the cab. Things between my father and I were simple then, and I was more interested in his opinions on my drawings and dolls than what he thinks about industrial agriculture.

No, we don’t always agree about things like pesticide use, meat consumption, farm subsidies, and water quality. But we still share an important bond. And listening to his stories has enhanced and humanized my understanding of the systems oppressing all of us, and allowed us both to reach a point where we can begin to understand one another.