Civil Eats: Hawaii Shows States’ Power to Regulate Pesticides

by Lisa Held | June 20, 2018

“I apologize if my anger comes across too strongly,” says Gary Hooser, on the phone from the island of Kauai in Hawaii, “but these companies sued my county for the right to use pesticides next to our schools and not tell us about it. And they can’t do that anymore.”

Hooser is a local policy advocate who has been elected to several county and state offices over the years and now serves as the president of the board of directors for the Hawaii Alliance for Progressive Action (HAPA). This week, his anger is mixed with a sense of victory.

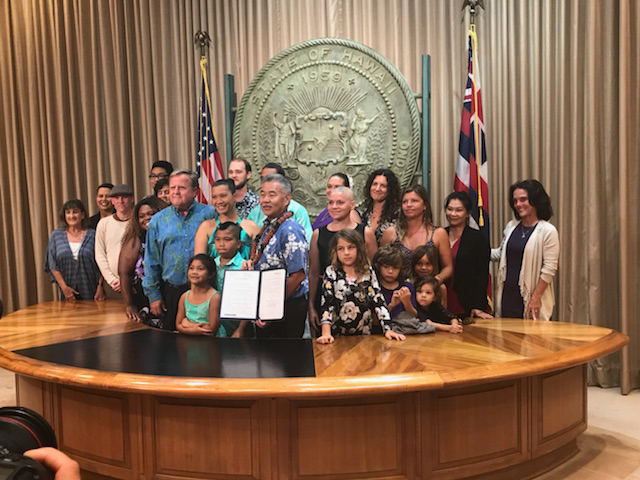

On June 13, Governor David Ige signed Senate Bill 3095 into law, making Hawaii the first U.S. state to completely ban the use of the pesticide chlorpyrifos. The law also requires agrochemical companies including DuPont-Pioneer and Dow Chemical (one of the main manufacturers of chlorpyrifos) to share information about when and where they apply all restricted-use pesticides—including atrazine and paraquat—and sets up buffer zones around schools to protect children from pesticide drift.

The bill was born out of nearly a decade of grassroots organizing by community activists and organizations in the islands, including HAPA, the Pesticide Action Network (PAN), Protect Our Keiki [children], and others.

“It’s the first bill in decades, of any kind, that I’m aware of, to regulate big agriculture in Hawaii [at the state level],” Hooser says. “It’s a miracle, in some sense, that we passed this.” Not for lack of trying: Hawaii has been on the frontlines of community activism for years to regulate pesticide use in the state.

The bill is especially significant on the national stage because it prohibits the use of “pesticides containing chlorpyrifos as an active ingredient” beginning January 1, 2019, with some opportunities for exemption through 2022.

In 2000, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) banned the popular insecticide for household use. Then, based on further research on its potential health risks, especially regarding developmental problems in children, the EPA recommended banning the chemical from agriculture nationwide.

However, when Scott Pruitt took over the agency under President Trump, he reversed course and rejected the agency’s own recommendation. Pruitt has also pushed back against a recent report that showed the use of chlorpyrifos endangers nearly 40 species of fish and their marine habitats.

For those who believe chlorpyrifos is a threat to both human health and the environment, Hawaii demonstrated that it’s possible for states to move forward on pesticide regulation, despite a rollback of proposed federal regulations.

Jay Vroom is the president and CEO of CropLife America, a trade organization representing the agrochemical companies that manufacture pesticides, including chlorpyrifos. In a statement emailed to Civil Eats, Vroom said pesticides are subject to “years of diligent and thorough testing. It is crucial to remember that pesticide registration decisions … are based on extensive scientific data to establish that these products are safe to human health and the environment when used properly.”

The statement adds that “a total ban of any product that ignores this scientific, risk-based regulation is informed not by science but by politics and has the potential to lead to confusion in the marketplace, leaving farmers and other pesticide users without the tools they need.”

For Hawaii residents, though, banning the restricted-use insecticide is one piece of a much bigger issue their communities have been facing for many years. Because the climate there allows for year-round growing seasons and the islands are isolated, agrochemical companies have flocked to the state to grow seed crops and do field-testing, a development that was chronicled in the recent documentary, “Poisoning Paradise.”

“For too long, these corporations have used Hawaii as its test grounds, poisoning our land and our people,” says Leslee Matthews, a Pesticide Action Network (PAN) policy fellow based in Honolulu.

According to a recent report, in 2015, more than 25,000 acres of land were used by Monsanto (now owned by Bayer), DuPont-Pioneer, Dow Chemical, Syngenta, and BASF for genetically engineered seed crop operations in Hawaii. Since 1987, Hawaii has hosted more cumulative field trials than any other state, and between 2010 and 2015, herbicide resistance was the most frequently tested trait, suggesting high applications of herbicides during those trials.

Between 2007 and 2012, DuPont-Pioneer alone applied 90 different pesticide formulations on Kauai, spraying on two-thirds of the days in that period an average of 8.3 to 16 applications per day. The report also found that restricted-use pesticides like chlorpyrifos, which are classified that way because they are considered more dangerous, were used in large amounts, especially on Kauai.

While the report provides a broad picture of frequent field trials and pesticide use, agrochemical companies have largely not been required to reveal what or when they were spraying. And because Hawaii is small, many of the fields are located close to residential communities and schools.

Reports of children getting sick at school as a result of pesticide drift was one of the main sparks that launched the movement. At Waimea Canyon Middle School in 2008, for example, several students and teachers were sent to the emergency room due to headaches, nausea, and dizziness after a chemical smell hit the school.

“My children attend an elementary school across the street from fields that are regularly sprayed with a variety of pesticides,” says Keani Rawlins-Fernandez, a lawyer and advocate based on the island of Molokai who is now running for Maui County Council.“This elementary school is the only one with a Hawaiian immersion program on Molokai,” she says. “The decision to send my children to school in a setting that builds a strong foundation for their identity as Kanaka ‘Oiwi [Native Hawaiians], and children of this place, taught in the language of their ancestors, while potentially being exposed to dangerous chemicals constantly weighs heavy on me, as their mother.”

Rawlins-Fernandez says the issue has also broken up local communities, since some believe the jobs companies provide outweigh the health and environmental risks and resent the residents who challenge the companies.

However, enough opposition had built up by 2013 and 2014, that Hooser decided to introduce a Kauai county ordinance that would mandate pesticide disclosure and school buffer zones.

“It was an epic battle—thousands of people marching in the streets, the largest, longest public hearings ever in Kauai,” he says. The ordinance passed. Shortly after, both Maui and Hawaii counties passed similar ordinances. Then, the chemical companies fought back and a federal judge overturned all three laws on the basis that the counties couldn’t preempt state law on the issue.

‘The judge clarified, though, that the state could take action,” says Paul Towers, an organizing director and policy advocate at PAN North America. “It sort of forced advocates to say, ‘Okay, we’ve got to take this to the state.’”

Advocates then shifted to focus on getting state legislation passed that would achieve the same goals but at a higher level.

“It was similarly difficult but … when we started working at the state level, we had a coalition already,“ Hooser says. “Every day we had people knocking on legislators’ doors, sending them emails, and calling them.”

And at the state level, Towers explains, the law is much less likely to be overturned, especially since a judge already ruled it was in the state’s power to regulate pesticide use. Overturning a legislature-passed bill is a tall order, Towers says, although he notes, “what seems more likely is that they try to sabotage implementation of the law to delay its effect. Or for the company to voluntarily cancel use in Hawaii in efforts to try and keep it on the market in other states, as well as globally.”

In the meantime, Syngenta has responded to the news about Hawaii’s law and other international pushback against pesticide use by warning of global food shortages. Independent experts have repeatedly found that the claim that pesticides are needed to feed the world’s growing population is a myth.

“Hopefully this is a sign for other states that they can take the lead, especially given the vacuum of leadership at the federal level,” Towers says, pointing to the fact that California, Maryland, and New Jersey are already considering implementing restrictions or bans on chlorpyrifos.

“It shows that you can stand up to powerful industrial agriculture interests and do things in the best interest of frontline communities.”

This article was updated to reflect the fact that California is considering tighter restrictions on chlorpyrifos, but not a full ban.