Civil Eats: Can Teaching Kids to Cook Make Them Healthier Later in Life?

by Lela Nargi | HEALTH, Nutrition, School Food | July 30, 2018

New research suggests that learning how to cook as a young person leads to better eating practices—and better health—later in life.

It’s a hot afternoon in late May and Sierra Sutton, Risa Luk, and Sissi Mesa, all seniors at the High School for Environmental Studies in Manhattan, are roasting trays of broccoli and potatoes to serve for lunch at the Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen. The meal is the culmination of a year-long, in-school food course developed by the Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture in Tarrytown. The primary aim is to educate kids about the complex workings of the food system and how they can help to change it. The course also aims to teach students a little something about cooking, nutrition, and food budgeting—once the purview of the home economics classes offered across the U.S.

A continuing epidemic of obesity among Americans of all ages—affecting nearly 20 percent of children age 6 to 19 and almost 40 percent of adults—has led food advocates such as Michael Pollan, Salt, Sugar, Fat author Michael Moss, and the late Anthony Bourdain to call for a return to home ec for everyone. Teach them how to feed themselves well, the reasoning goes, and you’ll give them the tools to stay healthy into and throughout adulthood. It’s a logical enough premise, and one that informs a growing number of cooking classes that have been springing up around the country. But until earlier this year, there was no concrete scientific evidence that it works.

Then, in March, the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior published the results of a 10-year longitudinal study conducted by researchers at the University of Minnesota’s School of Public Health. The aim of the study, which tracked more than 1,100 participants, was to answer a simple question: Can knowing how to cook as a young person lead to healthier eating practices in adulthood? The researchers arrived at a compelling—if unsurprising—conclusion: It can.

Those who self-reported that they had at least “adequate” cooking skills at the start of the study, which began in 2002 when the participants were between the ages of 18 and 23, were “more likely to be preparing meals with vegetables and eating less fast food” as adults 10 years later, the research found. And those who went on to have children were more likely to sit down with them to regular family meals—which previous studies have already linked to eating more vegetables and fewer processed foods.

“These results demonstrate that the opportunity to develop cooking skills early in life may have benefits that extend through adulthood and maybe even into the next generation,” says the study’s lead author, Jennifer Utter, who teaches public health nutrition at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. They have been received with enthusiasm by proponents of kid-centric cooking classes, who see the study as a first step in validating the benefits of their programs.

Shreela Sharma, a University of Texas epidemiology professor and co-founder of a Houston-based nonprofit called Brighter Bites, says, “we [now] know more with regard to the impact that behaviors [like cooking healthy meals] have” on long-term health outcomes.

Combining Education with Access

Critics point out that turning the tide on poor diet and its related diseases requires more than just teaching kids how to cook food that may not be available to them at home. What’s needed, says Hank Herrera, president of the non-profit Center for Popular Research, Education & Policy (C-PREP), is “building the local food production and distribution infrastructure that would bring healthy food to communities lacking access.”

Utter and other experts who study nutrition, health, and food insecurity agree. Across the country, a number of organizations running cooking classes for children also focus on ensuring access to healthy food as well as nutrition education.

For six-year-old Brighter Bites, providing fruits and vegetables to low-income urban families—as well as teaching them how to prepare it—is paramount to its mission. Its food-bank partners truck in rescued produce to over 100 sites at (mostly) elementary schools, but also summer camps, and daycare and Head Start centers in Texas, New York, Washington, D.C., and Southwest Florida. Parent volunteers pack the produce into bags along with accompanying dual-language recipes families can use at home. The kids receive in-class nutrition education, with teachers often incorporating the same produce the families are receiving into their lessons.

To Sharma, education is essential to helping families shift—or shift back—to healthier eating. For example, she points out that new immigrants—many of whose children attend schools that Brighter Bites serves and who often arrive in the U.S. with cooking skills and traditions of their own—struggle with mundanities like knowing where to grocery shop. And there’s often a desire to assimilate.

“Part of being an immigrant is wanting to fit in,” Sharma says. “If the [local] norm is to eat Happy Meals, then that’s going to be what you engage in.” Add to that a limited budget and you get families hesitant to purchase healthier foods they’re not sure their kids will eat. Educating children—who may need to taste new foods multiple times to decide if they like them—brings some mealtime agency back to parents.

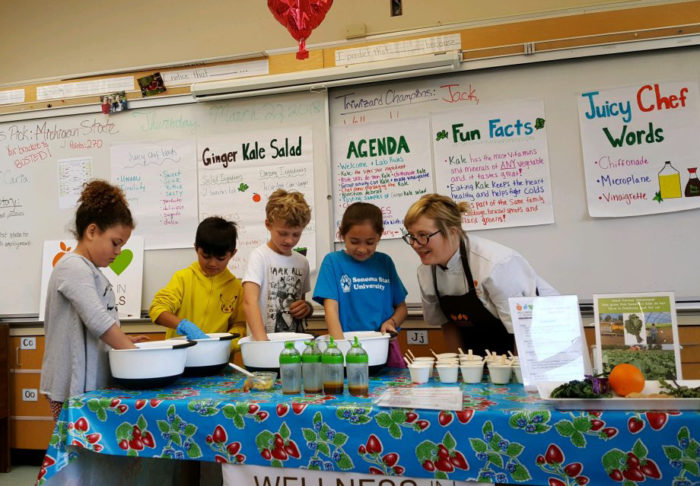

The New York City-based Wellness in the Schools (WITS) program for the past 12 years has been committed to increasing access to healthier food through school lunches where, says executive director Nancy Easton, “chicken fingers and processed food have become the norm.” Through its Cook for Kids program, WITS chefs, who are trained culinary professionals, work with 122 public elementary schools, mostly in New York City (with a few in New Jersey, Florida, and California), to modify cafeteria menus, train school staff, and provide nutrition education to students.

Says Easton, “When vegetarian chili shows up on [your tray] on Wednesday, you’re much more likely to eat it if you made it with a chef in your classroom first.”

The group also sends recipes home to parents.

Serving healthier school lunches to kids is probably “not going to tip the scales on obesity,” Easton acknowledges. “But that one school lunch a day is often a child’s only hot meal. It should be as nutritious and delicious as possible, so he eats it, but also be an example of what he should be eating.”

From its home base in Chicago, Feeding America’s primary mission is not education—it works to provide food to people in need within its nationwide, 200-food-bank network. But as the organization has hustled to increase healthier food offerings—distributions are now 31 percent produce, up from 17 percent in 2008—it’s also been pushing to offer its clients what managing director of community health and nutrition Michelle Berger Marshall calls “sustainable interventions,” such as healthy-eating classes for adults, teens, kids, and families offered by some of its food banks.

One of them, The Food Bank for NYC, partners with public elementary schools to teach CookShop classes to students as well as their parents. Marshall sees the latter component as essential to placing at least some of the burden on caretakers, who control food budgets and meals, noting that kids instructed to eat more fruits and vegetables can be stymied when they find that “all they have at home is Hamburger Helper,” she says.

Home Ec is Still With Us

These models represent a fraction of the current crop of food-centric programs being run around the country, each with its own particular mix of imperatives, partners, and funders. The three primary examples here include access to their mix; many others—like those offered by Stone Barns and Alice Waters’ Edible Schoolyard—hone in on the knowledge component as a means to eventually giving kids some of the resources they need to fix a broken food system

And home ec still exists—only it’s called Family and Consumer Sciences now. Some 5 million American public middle and high schoolers study it every year, learning everything from how to prepare for a career in the food sector, to gardening, nutrition, meal-planning, and cooking, according to Camelle Kinney, chair of the Department of Family and Consumer Sciences at North Star High School in Lincoln, Nebraska.

This program spans multiple states, but many others are local—a testament to the complexities of funding as well as the differing needs of communities. And while that may be frustrating for organizations that might like to have a broader impact, C-PREP’s Herrera thinks staying small is a good thing. “A restoration of equitable ownership of the means of production and exchange of food … has to happen at the local level,” he says. “Just as education has to happen at the local level, where citizens take back control of [it].”

For study author Jennifer Utter, it’s the collaborative, multi-pronged efforts—whether small or large in scale—that are critical to ensuring food-based classes for kids are successful. “All young people should have the opportunity to cook,” she says. “But without addressing the bigger challenges of food insecurity, poverty, and the over-abundance of highly processed … foods, the impact on public health will likely be minimal.”