Bloomberg: Why America Pays 50% More for Chicken, by Deena Shanker

Why America Pays 50% More for Chicken

The $29 billion poultry industry has been accused of hatching a plan to limit production.

by Deena Shanker

September 28, 2016, 4:00 AM MDT

What do you call it when would-be competitors embark on a unified strategy to limit supply, drive up prices, and bilk customers of their hard-earned cash? An antitrust conspiracy, of course. But what do you call it when producers of chickens, a staple of the American diet (Wall Street even has a chicken wing index), allegedly go so far as killing their birds early, shipping more eggs, and buying one another’s products to keep public supply low?

According to food distributors suing the industry, it’s called “capacity discipline.”

The $29 billion industry that churns out 90 percent of America’s chickens has engaged in a price-fixing scheme for years, according to the first of a half-dozen lawsuits filed in Chicago federal court this month. And that artificial premium has been passed on to consumers: You’ve been paying 50 percent more for that supermarket rotisserie bird, the lawsuits claim. While producers have been accused of rigging the market before, this litigation may be the largest effort yet to bring such practices to light.

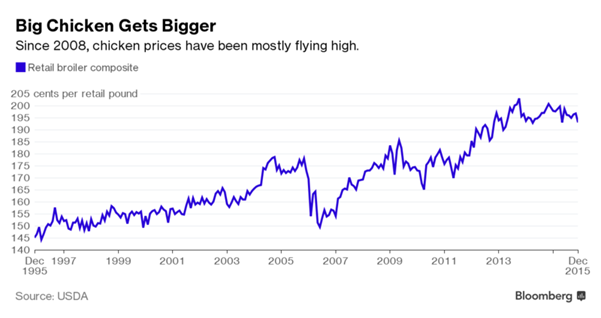

For decades, the price of a broiler—the standard, non-organic, non-halal, non-kosher chicken that makes up 98 percent of what’s sold—followed a boom and bust pattern: Rising demand led to higher prices and more production, then to oversupply and a drop in prices. In 2008 that began to change. The reason, according to the 113-page lawsuit, is that the producers launched a coordinated strategy, one facilitated by shared proprietary information and countless industry events involving top executives. All of the companies raised fewer chickens, holding down supply and driving up the price of the country’s most popular meat.

Last year, U.S. producers raised 8.69 billion broilers weighing 53.4 billion pounds, according to the Department of Agriculture (PDF). Exports are expected to reach a record 10.8 million tons in 2016, according to another USDA report (PDF). Brazil and the U.S. account for two-thirds of the world’s broiler supply.

Tyson Foods Inc., Pilgrim’s Pride Corp., and Simmons Foods Inc. have denied the antitrust allegations and said they would fight the litigation, an antitrust class action led by New York food distributor Maplevale Farms on behalf of other middlemen that purchase directly from the producers. (Additional defendants either declined to comment or didn’t respond.) The plaintiffs seek to stop the alleged conduct and demand triple damages.

“We believe there are real anomalies in the broiler chicken market that have increased prices,” said Joe Bruckner, a lawyer with Lockridge Grindal Nauen PLLP who helped bring the case. By digging into earnings calls, industry calendars, presentations, and other publicly available information, Bruckner and his fellow attorneys have pieced together what they allege to be a vast price-fixing scheme.

Chicken producers, meanwhile, point to higher corn prices as an explanation for higher bird costs. In an Oct. 14, 2014, op-ed in the National Provisioner, President Mike Brown of the National Chicken Council wrote: “We would like to produce more pounds of chicken, but unfortunately we are not there yet.” The reason, he said, was ethanol: Diverting corn to ethanol production was making it pricier for chicken producers. Brown co-authored a similar op-ed in the Wall Street Journal in May 2015. (The National Chicken Council declined to comment.)

Bankruptcy and the Brazilian meat giant

The court complaint traces the alleged collusion back to 2008, when—thanks to high feed prices, debt, and an oversupplied chicken market—Pilgrim’s Pride, one of the country’s largest poultry companies, was facing serious financial difficulties. It brought in consultants from Bain & Co. to help find a solution, the lawyers contend. This wasn’t enough: In December, Pilgrim’s filed for bankruptcy and eventually became part of meat conglomerate JBS USA Holdings, a unit of São Paulo-based JBS SA. But those consultants did, according to the complaint, offer some sage advice: Pilgrim’s Pride needed to cut supply so prices would rise. (Bain didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

There was a catch, though. Chickens are a commodity: Tyson’s chicken is indistinguishable from Pilgrim’s, which is indistinguishable from that of other defendants, such as Perdue Farms Inc., so this plan would work only if the whole industry participated.

That’s what began to happen in 2007, according to the lawsuit, when Tyson’s, Pilgrim’s, and a few smaller producers reduced their output. At first, others didn’t play ball. But the next year, the plaintiffs said, the industry began to take a more coordinated tack, with a joint effort to cut supply across the board. “We see an uncanny amount of coordination and communication between supposed competitors,” Bruckner argued.

As part of so-called capacity discipline, producers allegedly began announcing their plans to cut back, prodding competitors to do the same. In January 2008 earnings calls, just a few days after poultry executives attended the International Poultry Expo in Atlanta, Tyson Chief Executive Officer Dick Bond, Pilgrim’s Chief Financial Officer Rick Codgill, and Sanderson Farms CEO Joe Sanderson each alluded to a major industrywide shift, the plaintiffs said. Bond referred to raising prices, Codgill explained that Pilgrim’s alone couldn’t handle needed supply reductions, and Sanderson said cuts were “probable.”

Within months, the cuts were under way: Greeley, Colo.-based Pilgrim’s Pride started closing plants. Instead of jumping in to fill the supply gap, rivals followed suit, according to the distributors. From April 3 to April 11, multiple companies made announcements about scaling back: Fieldale Farms, Simmons Foods, Cagle’s, Wayne Farms, OK Foods, and Koch Foods all announced reductions ranging from 2 percent to 8 percent, the complaint stated. On April 14, Pilgrim’s Pride said more were coming. The cuts—and calls for more—continued at a steady pace, and prices began to rise in mid- to late 2008, hitting record highs through late 2009.

“It makes sense to cut back production if, and only if, your competitors cut back, too,” said Peter Carstensen, a former antitrust lawyer for the U.S. Department of Justice and a professor at the University of Wisconsin Law School. Therefore, he said, such behavior would create “an inference of collusion.”

But not everyone sees the simultaneous cutbacks in a negative light. “It’s very predictable,” says Tom Elam, an economist who has acted as an independent consultant to the National Chicken Council and some of the defendants. He also worked with insurance companies in a lawsuit against Tyson. He, like the industry lobbyists, pointed to the high corn prices as the driving force behind decisions to cut chickens.

Determining whether corporate behavior rises to the level of antitrust is generally the purview of the Justice Department. So where does the Obama administration and its recently active antitrust division land on the chicken conundrum? They declined to comment.

“The U.S. departments of Justice and Agriculture have become deeply hesitant to file large, complex cases that allege monopolistic abuses” in America’s massive agriculture industry, said Christopher Leonard, whose book, The Meat Racket, outlined the purported scheme in 2014. “It seems that the federal government has lost its appetite to fight such cases, which leaves the job to private-sector lawyers.”

Thinning out the supply chain

The cuts in production were unusual, the distributors claimed, not just because they were done in a coordinated fashion but because they “went further up their supply chains than ever before to restrict their ability to ramp up production for years into the future.” The producers didn’t just slaughter chickens before they could market them, or sell (or break) eggs before they could hatch: They reduced their breeder flocks, limiting the number of eggs that could be laid in the future, in a move the complaint called unprecedented. Elam said longer-term cuts can be explained away by the ethanol program, since it sunsets in 2022. “As far as they could see, a large portion of their feed supply was going to be diverted into ethanol,” he said.

Besides seeing one another at industry events, the chicken executives also exchanged information through Agri Stats, a data service that helps them monitor each other’s business. Agri Stats ostensibly collects detailed, proprietary information from all of the companies, including housing used, breed of chicks, average sizes, and the all-important production numbers. It acts as a benchmarking service, distributing anonymized individual producer information. In reality, the lawsuits contend, it’s very easy to know which company is which if you’re paying attention. “It’s the great enforcement device,” said Carstensen. “It’s a way to check if [competitors] are cutting back on supply.”

Agri Stats says it’s “confident in the lawful conduct of [its] business,” declining further comment.” Elam notes that Agri Stats practices are similar to what other industries do, pointing to the automotive industry’s publication of prices, as well as the airlines.

Selling eggs to Mexico

As prices rose in late 2009 and early 2010, the scheme began to collapse, the distributors claimed. Production rose and prices fell. By then, though, producers knew what to do. “Defendants had learned the value of coordinated supply reductions in 2008,” the complaint alleged, “so were quick to react with a new round of publicly announced production cuts in the first half of 2011.” Again, prices went up.

The lawyers say that Tyson, for example, was so committed to this strategy that it began buying competitors’ chickens instead of growing its own, which would have been cheaper, under what was dubbed a “buy vs. grow” strategy. The defendants also exported eggs to Mexico, rather than build up their U.S. flocks, according to the complaint.

Last year, the industry hit a small bump that drove prices down again: avian flu-induced export limits. By this May, however, most of those bans were lifted. And thanks to now lower feed and other production costs, profitability remained steady or went up. That month, Tyson reported a rising profit margin growth for broilers between 9 percent and 11 percent.

“If there was a conspiracy, it was remarkably unsuccessful,” said Elam, the economist, pointing to acquisitions of poultry companies during the alleged period of collusion, including the JBS-Pilgrim’s deal and Mexican poultry group Industrias Bachoco’s purchase of OK Industries. “Companies that are healthy and are making money don’t go out looking for buyers.”

To prove their case in court, the food-distributors’ lawyers face a tougher job than simply connecting dots they allege add up to illegal behavior. The cuts in production, shared proprietary information, and opportunity to make agreements all may point to an antitrust conspiracy, but they don’t necessarily establish it, said Carstensen. “You’re asking the court to infer collusion,” he said. But he added that it may not be such a leap: “With Agri Stats, those meetings, and then, if you can line up the conduct to show reasonable uniformity, that would pretty much do it.”