Bloomberg: The U.S.-Mexico Wage Gap Is Actually Widening Under Nafta

By Eric Martin and Nacha Cattan | November 28, 2017

What’s the opposite of a growth miracle? Whatever the term, it applies in spades to Mexico in the Nafta era.

Poor countries are expected to grow faster than rich ones, and they need to. Trade agreements are supposed to help. Yet by almost any benchmark — certainly the ones trumpeted by the deal’s architects a quarter-century ago — the Mexican economy’s performance has been dismal.

Signs that read “Mexico Is Better Without NAFTA” are held during a protest in Mexico City.

Photographer: Brett Gundlock/ Bloomberg

“The main idea was to promote convergence in wages and standards of living,’’ said Gerardo Esquivel, an economics professor at the Colegio de Mexico. “That has not been achieved.’’ And what meager growth there’s been, says Esquivel, has mostly gone to “the upper part of the distribution.’’

For an emerging market, Mexico has an impressive collection of billionaires, including the world’s sixth-richest man. Its poverty rate, meanwhile, is still around early-1990s levels — more than half the population, encompassing a permanent class of the underemployed. Crime and corruption are rampant.

All this poses a problem for the U.S., especially now that Donald Trump’s in charge. Mexico’s glacial economy means there’s still a lively incentive for the things Trump hates: the flow of underpaid Mexican labor northwards, and American factories the other way. No wonder, as his trade team trudges through round after round of renegotiation, that the U.S. president is still threatening to blow up the pact altogether.

It’s a much more urgent matter for Mexicans. And they’ll have a chance to do something about it in presidential elections next year. The early frontrunner, leftist Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, says he’ll usher in a new economic model. What role Nafta would play in that, if any, remains vague.

In Mexico’s policy circles, there’s little inclination to blame Nafta. Some point out that, while the economy clearly hasn’t boomed, it’s at least avoided the busts that sunk several Latin neighbors in the last two decades. Others say the trade pact couldn’t be expected to solve deep-seated problems on its own.

“To hold Nafta responsible for overall growth in Mexico is putting too much weight into Nafta,” central bank Governor Agustin Carstens said in an interview on Monday. “It’s a very important element,” he said. “But Mexico needs to take care of many different assignments in other areas to make the Mexican economy more productive and really exploit our full capacities to grow.”

Mexican President Salinas, U.S. President Bush, and Canadian PM Mulroney attend the NAFTA signing in 1992.

Source: Bettmann via Getty Images

“Mexico’s basic mistake was to assume that integrating into the world economy, and the U.S. market in particular, would suffice,’’ said Dani Rodrik, an economics professor at Harvard University. “Other aspects of development strategy were ignored.’’

‘Four Tires’

Here, every analyst has a different list. Ruben Ojeda, an official at Mexico’s Finance Ministry in the 1980s, starts with the economy’s basic levers. He says policy makers, burned by a traumatic devaluation during the so-called Tequila Crisis at the end of Nafta’s first year, kept the monetary settings too tight long afterward — fixated on inflation (the central bank’s sole mandate) instead of growth.

Ojeda, now a director at investment firm View Capital Advisors in Dallas, also says that Mexico didn’t learn a key lesson from the most successful emerging economies: industries need to be nurtured and protected before they’re exposed to competition.

Mexico’s car industry, for example, got plenty of government support pre-Nafta, so “it worked very well once it was liberalized,” he said. Other sectors didn’t enjoy that advantage, “and they essentially disappeared.”

What about the workers at those successful auto factories, though? Their stagnant wages are making waves at the Nafta talks. In Mexico City this month, Jerry Dias, head of the Canadian union Unifor, pointed out that employees at U.S. and Canadian car plants can buy the vehicles they produce with five months’ wages. “A Mexican worker in five months can only buy four tires and a steering wheel,” he said. “It’s an absolute disgrace.”

It’s not just labor making that case, north and south of the Rio Grande. Trump and his commerce secretary, Wilbur Ross, have complained about it too – channeling frustrations that helped the U.S. president to sweep the Rust Belt on his road to the White House.

Getting Mexicans a pay rise has become an unlikely priority for his trade team – and for some Mexican business groups too. One of them, Coparmex, has been lobbying for a higher minimum wage, saying too many workers struggle to afford even basic goods. The rate will rise 10 percent to 88 pesos ($4.74) a day next month, but that’s only about half the increase called for by Coparmex, let alone the much bigger jump that would be needed to regain pre-Nafta purchasing power.

For the critics, low pay isn’t an accident. It’s a policy, and one that illustrates a wider point: Nafta’s Mexican cheerleaders thought that all the demand needed to achieve economic liftoff would come from abroad. They neglected drivers of growth on the home front. Esquivel lists them: “Higher labor income, higher investment by private firms which don’t get access to credit, and better spending by the government.”

“We don’t have any of those three elements,” he said. “It’s actually surprising that we grow even the little that we grow.”

‘Left in Suspense’

And four-fifths of the external demand comes from a single country — now governed by Trump. If evidence of economic failure in the Nafta years has accumulated slowly, awareness of the political risks exploded on U.S. election day last year. Economy Minister Ildefonso Guajardo acknowledges the point.

“We slept on our laurels,” Guajardo, who heads Mexico’s Nafta negotiating team, said in July. “We need to diversify, so that next time there’s an election in Washington, the Mexican economy isn’t left in suspense.”

Revving up the domestic engine is a favorite theme of Lopez Obrador, known as Amlo. Another is sharing the pie more fairly. Mexico has the most unequal income distribution among the 35 OECD members. Carlos Slim, one of the winners from Mexico’s flagship privatization program, and three other billionaires hold wealth equal to about 8.5 percent of GDP, more than double the mid-1990s level, according to research by Esquivel, who’s worked as an external consultant for Lopez Obrador’s campaign.

“This kind of inequality is a boon to Amlo,” said Nicholas Watson at risk-analyst Teneo Intelligence.

Mexican Samsung?

Fiscal policy is the classical tool for fixing such imbalances. Mexico barely uses it. Government revenue is the lowest in the OECD — and because Mexico also runs one of the most balanced budgets, another cautious legacy of the Tequila Crisis, spending is constrained too.

That’s helped win investment-grade credit ratings across the board. It’s also meant a failure to invest in skills, especially in science and engineering, that would help workers add value, says Manuel Molano, deputy director of the Mexican Competitiveness Institute.

South Korea “invested heavily in the education sector, and the design parts of technology,” he said. “Where’s the next Mexican Samsung? There is none.”

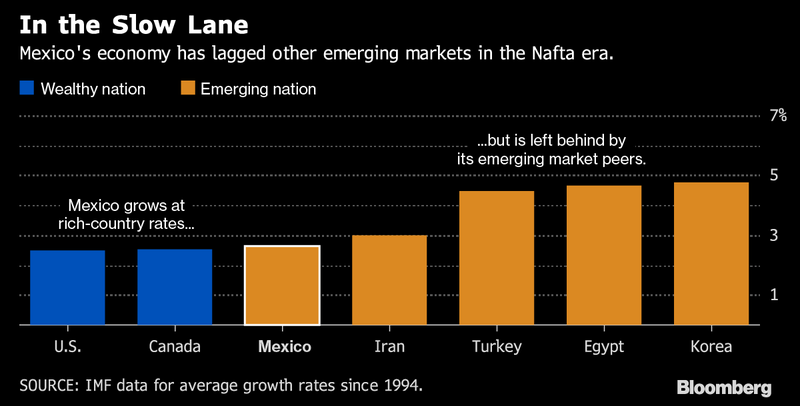

Korea’s a tough benchmark, but less stellar economies have also outgrown Mexico in the Nafta years: Turkey, which has a similar trade setup with its own giant neighbor, the EU; Egypt, which has suffered regime-change twice this decade; even Iran, almost completely frozen out of global commerce.

And Mexico’s own performance in the quarter-century before Nafta was significantly better. On a per-capita basis, it grew almost twice as fast, though some slowdown is normal as countries reach the middle-income bracket.

Some causes of the Mexican malaise aren’t strictly economic. Crime has surged, and is listed as a top concern of executives surveyed by the World Economic Forum. A brutal drug war has dragged on for more than a decade; even in its early years, policy makers estimated a hit to output of about 1 percentage point a year.

Almost every analyst cites corruption, and a judicial system that’s failed to tackle it. In 2015 alone, state governments misappropriated about $1.4 billion of federal funds, according to auditors.

That money could have been used to help develop Mexico’s poorer south, said Jonathan Heath, an economist at the Mexican Institute of Financial Executives. The region’s farmers haven’t benefited as factories sprang up along the U.S. border in the north. Under Nafta, “traditional agriculture was left to die,” said Ojeda.

It was in southern Mexico that the most dramatic challenge to Nafta emerged — on the day the trade pact took effect. In January 1994, Zapatista rebels and their masked leader, Subcomandante Marcos, launched a violent revolt.

The utopian ideas of the guerrillas have failed elsewhere in Latin America. Their uprising was rapidly crushed. Their vision of a Nafta-era Mexico, with entrenched inequality, impoverished farmers and increased dependence on the U.S., has proved harder to dispel.

— With assistance by Andrew Mayeda, Andrea Navarro, Chloe Whiteaker, and Catarina Saraiva

It makes you wonder why republicans always believe in trickle down but in instance after instance, there is little trickle down when policies overly favor the “rich”. Why aren’t democrats pushing trickle up economics as an alternative? Businesses do business. The more money the average person in the person has, the larger the market for business goods and demand for their products so they can make more money. Trickle up. When all the wealth is concentrated at the top, as it is in Mexico and increasingly the United States, the economy just doesn’t grow as fast because all the gains go up due to national policies of government like taxation, justice, and other factors. A large middle class and the demand it can create in an economy grows the economy. instead of just growing the stock market. More money in the hands of people who spend it on goods in the economy allow good businesses to grow. Just giving money to corporations or the super rich doesn’t grow the economy. It just makes them richer and more influential when it comes to government policies. Then they tend to tip the scales of the market and government action to benefit them, not the general welfare.

If one company came into Mexico and invested 100 billion dollars but most of the income from that 100 billion went to just a few while the government fails to capture some of those gains for the public good then how does that increase the wealth of the nation? It just increases the wealth of those capturing all those gains. The economy as a whole hasn’t even felt the 100 billion dollars invested. Thanks for the article. Due to the incompetence and corruption of money in our politics, our politicians have it all backwards. Instead of policy that corrects bad behavior (money funneled through offshore entities to hide increases of wealth from taxes for example) they instead make policies rewarding that bad behavior.