Bloomberg Businessweek: ‘I Need More Mexicans’: A Kansas Farmer’s Message to Trump

An undocumented immigrant is detained by the U.S. Border Patrol near the U.S.-Mexico border. Photographer: John Moore/Getty Images

By Michelle Jamrisko | June 20, 2017, 6:00 AM MDT

Growers and dairies lobby for a path to legalization for the undocumented workers who power their businesses.

Undocumented immigrants make up about half the workforce in U.S. agriculture, according to various estimates. But that pool of labor is shrinking, which could spell trouble for farms, feedlots, dairies, and meatpacking plants—particularly in a state such as Kansas, where unemployment in many counties is barely half the already tight national rate. “Two weeks ago, my boss told me, ‘I need more Mexicans like you,’” says a 25-year-old immigrant employed at a farm in the southwest part of the state, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he’s trying to get his paperwork in order. “I said, ‘Well, they’re kind of hard to find.’”

Arrests of suspected undocumented workers have jumped 38 percent since President Donald Trump signed a pair of executive orders targeting immigration in January. The crackdown is having a deterrent effect along the southern border: Apprehensions by U.S. Customs and Border Protection totaled 118,383 from January through May, a 47 percent decrease from the same period last year, which indicates fewer people are trying to enter the U.S. illegally. Michael Feltman, an immigration lawyer in Cimarron, Kan., says his firm has seen more people coming in with naturalization questions over the past six months than over the previous four years combined. “I’m really worried every little traffic ticket’s going to turn into detention,” he says.

Others feel the same way. “The threat of deportation and the potential loss of our workforce has been very terrifying for all of us businesses here,” says Trista Priest in Satanta, Kan. She’s the chief strategy officer at Cattle Empire, the country’s fifth-largest feed yard, whose workforce is about 86 percent Latino.

In Haskell County, where Cattle Empire is the biggest employer, 77 percent of voters cast ballots for Trump, compared with 57 percent statewide. But Priest and other employers interviewed for this story complained that the immigration policies emanating from Washington, 1,500 miles away, clash with the needs of local businesses.

Representative Roger Marshall, a Republican whose district includes southwest Kansas, says immigration is the No. 1 concern he hears about from constituents. The freshman congressman says he’s confident that once the border is secure, “President Trump will look at this, too, as an economic problem.”

The two executive orders issued in January call for a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border and prioritize the deportation of undocumented immigrants who’ve been convicted or charged with “any criminal offense.” The language is so broad that all the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S. could be targets, given that anyone who’s evaded border inspection or overstayed a visa could be charged with a misdemeanor or fraud.

Trump has said that even as he ramps up deportations, he doesn’t want to slam the door on immigrants. He’s proposed a merit-based system akin to those of Australia and Canada. Those countries confer legal status via a point system that rewards those with higher education, better employment histories, and language skills. He’s also spoken generally about reforming the short-term visa program for farmworkers. Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue told Congress last month that the existing H2A visa, which admits seasonal workers, “has not been as successful as we would like, and it’s very onerous,” especially for smaller farms, to navigate all the paperwork.

But those proposals do not offer a pathway to legalization for those who are already in the country, which is what agriculture and other industries including construction and restaurants have been calling for. Joe Jury, who’s been farming in Ingalls, Kan., since the 1970s and has employed “probably well over 100 Hispanic immigrants,” wants immigration reform that emphasizes making it easier for foreign-born residents to work as much as it ensures that criminals are deported. “The visa system is so slow and so expensive,” he says. “The government has dug this hole, and now they’re trying to dig themselves out through enforcement.”

The American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) has proposed that, to “minimize the impact on current economic activity,” unauthorized agricultural workers already in the country should be granted permanent legal status once they prove they have worked in the industry for a set period of time. The AFBF has warned that an enforcement-only approach could slash industry output by as much as $60 billion annually.

Feltman, the immigration lawyer, says his clients would be more than willing to pay hefty fines for assured legalization. If each undocumented worker were charged $1,000 or $1,500, that would change political sentiment, he says. “The people that are the naysayers to all that might say, ‘That’s a lot of money for our country.’” Pew Research Center estimates that 375,000 undocumented workers are employed in agriculture.

“I didn’t come over here because I wanted to—my parents brought me here,” says the undocumented worker from southwest Kansas, who says he’s spent $24,000 on immigration lawyers and other expenses in his quest for legal status. “I’m here, I have to work.”

The price of milk would jump to $6.40 a gallon if U.S. dairy farms were deprived of access to immigrant workers, according to a 2015 report commissioned by the National Milk Producers Federation, which estimated that half of all workers in the industry are immigrants. Lingering in Congress are two separate bills that would modify the existing H2A agricultural visa program so that dairy farms can hire workers year-round rather than seasonally. In an April 18 statement in support of the legislation, the milk producers’ trade group said: “Without the help of foreign labor, many American dairy operations face the threat of closure.”

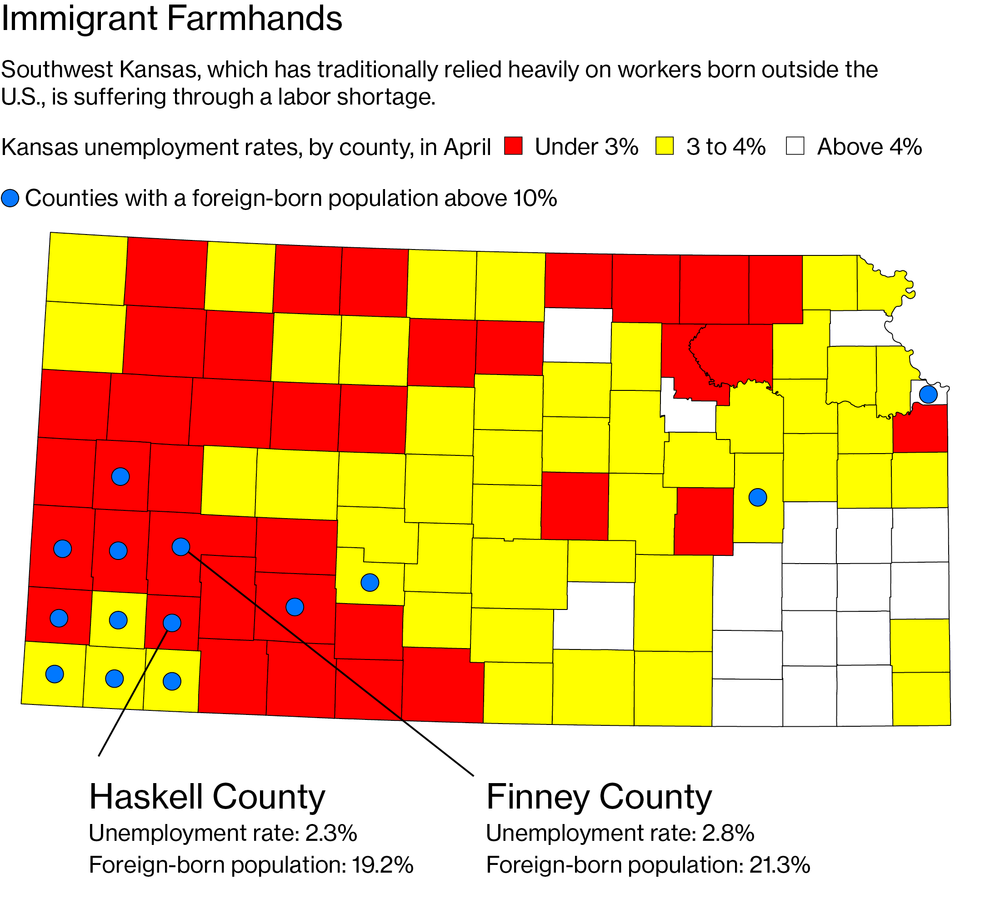

Kyle Averhoff, general manager of Royal Farms Dairy in Garden City, Kan., says he’s seen the flow of applicants slow in recent months as the labor market has tightened. Unemployment in Finney County, where Royal Farms is based, was just 2.8 percent in April, down from 3.1 percent a year ago. “We’ve gone to some of the highest-unemployment counties in our state and ran ads, and without success,” he says. An entry-level job at Royal Farms could pay as much as $40,000 in wages and benefits, with no prior skills required, Averhoff says: “For us the immigration issue is not about cheap labor. It’s been about finding people who have the aptitude and want to work in our industry.”

Averhoff’s pain extends beyond Kansas. An extreme shortage of agriculture workers, attributed to “recent changes in immigration policy,” was responsible for some growers in California discarding portions of their harvest in April and May, according to the Federal Reserve’s Beige Book, which surveys businesses. Meanwhile, U.S. homebuilders, whose optimism soared after the election on promises of deregulation and tax reform, are back to citing severe labor shortages as a big reason for their subdued spirits, according to survey data from the National Association of Home Builders and Wells Fargo & Co.

BOTTOM LINE – A group representing farmers has warned that an enforcement-only approach to immigration could slash industry output by as much as $60 billion annually.