Bloomberg BNA: As Factory Farms Spread, So Do Toxic Tort Cases

By Steven M. Sellers

Large factory farms increasingly occupy rural landscapes once dotted with small family farms, and their concentrated waste has produced a wave of toxic tort litigation.

Known as Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations, the facilities confine and raise large populations of livestock. Environmentalists say these operations supply food to such industry giants as Tyson Foods Inc. and JBS USA.

Common allegations in CAFO cases—stench from waste lagoons, sinking property values, tainted groundwater and swarms of flies—have propelled citizen suits asserting nuisance and other torts in Arizona, California, Illinois, Iowa, North Carolina, Wisconsin and other farming states.

As lawmakers from these big food-producing states push back with farm-friendly state and federal legislation, new liability theories are emerging to counterbalance what environmentalists and plaintiffs’ lawyers say are often tough court battles and a void in national and local regulatory enforcement.

And lawyers on both sides of the cases agree the legal landscape is expected to change even further as a result of a new federal appeals court decision that rejected the Environmental Protection Agency’s air emission reporting exemption for CAFOs.

Real Risks vs. Talking Points

Environmentalists and plaintiffs’ lawyers tell Bloomberg BNA that the increasingly centralized pockets of cattle, chickens, diary cows and hogs in the U.S. pose nationwide health and environmental risks that they are increasingly forced to sue over. At the same time, they say ineffective federal regulations and new laws are making it harder to prove their cases in court.

“EPA recently estimated that there are about 19,000 CAFOs in the country and that of those, about three-quarters probably discharge into waterways and should be regulated under the Clean Water Act,” Tarah Heinzen, staff attorney for Food & Water Watch in Washington, told Bloomberg BNA.

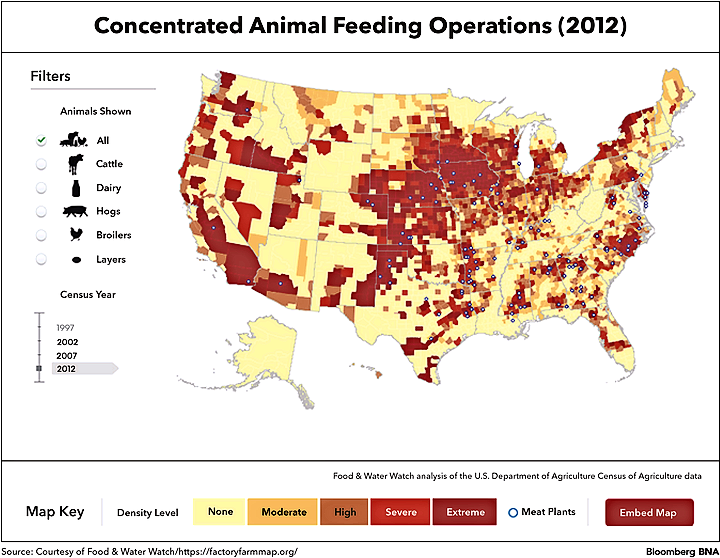

CAFOs are scattered all over the nation, according Food & Water Watch’s interactive Food Factory Map analysis of U.S. Department of Agriculture data.

“There’s a huge gap in knowledge, both in terms of how many facilities there are across the country, which ones are regulated, which ones should be regulated but are not and exactly where these facilities are,” Heinzen said.

Lawyers for the farms, however, say the risks are well-managed by properly-sited CAFOs, and that the operations are an economic necessity protected by right-to-farm laws in every state.

“There are certain plaintiffs’ groups that fundamentally believe that large animal feeding operations are unethical or have no place in the current agricultural industry in the United States,” Leah Ziemba, of Michael Best & Freidrich in Madison, Wis., told Bloomberg BNA.

“You see it permeating a number of the legal cases,” said Ziemba, who heads the firm’s agribusiness, food and beverage industry group.

“Most of the claims about odor and air emissions are talking points we’ve seen a hundred times that, frankly, lack a scientific basis for the allegations,” she said.

Wasting Away

CAFOs differ from traditional farms because livestock typically don’t graze in pastures. They’re confined, supplied with feed, and their waste is collected in lagoons for use as fertilizer.

EPA regulates CAFOs based on the type and number of animals they confine. It defines a large CAFO as an operation that confines, for more than 45 days in a twelve-month period, 1,000 or more head of cattle, 700 or more diary cows, 10,000 hogs or 125,000 chickens.

The farms produce a lot of animal waste. The EPA estimated in 2011 that confined livestock in the U.S. generate more than three times the raw waste produced by humans.

“Large farms can produce more waste than some U.S. cities—a feeding operation with 800,000 pigs could produce over 1.6 million tons of waste a year,” according to a 2010 report by the National Association of Boards of Health, which has counseled local health officials on ways to mitigate potential problems associated with CAFOs.

Suppliers used by five major agribusinesses—Tyson Foods, JBS, Cargill Inc., Perdue Farms Inc. and Smithfield Foods Inc.—produce a 162,936,695-ton “manure footprint,” according to a report issued in 2016 by the Environment America Research & Policy Center, a Boston-based environmental advocacy group.

CAFOs of sufficient size are subject to Clean Water Act regulations, but are largely exempt from Clean Air Act regulations on the theory that they don’t exceed emission thresholds of ammonia and hydrogen sulfide.

Improperly managed waste can jeopardize public health by sending nitrogen, phosphorus, sediments, pathogens, heavy metals, hormones and antibiotics into groundwater, according to the EPA and the USDA.

A worst-case scenario played out in 1995, when an eight-acre hog farm lagoon spilled 25 million gallons of effluent into the New River in North Carolina. It caused a fish kill, ruined crops and threatened drinking water for downstream communities.

Square Pegs, Round Holes?

Ineffective federal regulation of CAFOs is the root of the problem, environmental advocates say, citing a pending petition urging the EPA to strengthen its rules.

They also say the regulatory vacuum hampers citizen suits filed under such federal statutes as the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act.

“Part of the reason that these tools are often a square peg in a round hole is because EPA hasn’t fully utilized its authority under some of these laws to make regulations that clearly do apply to this industry,” Heinzen said.

“For example, in the Clean Air Act, we have regulation of certain pollutants when they are emitted from stationary sources, but EPA has never designated CAFOs as one of those source categories,” she said.

Another federal law, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, which governs solid waste disposals, appeared in a recent CAFO case in reaction to environmentalists meeting obstacles in suits under those other federal statutes.

Handing a local green group a rare victory against a CAFO under a national law, a federal court in Washington state said in 2013 that manure over-applied as fertilizer, resulting in runoff rather than absorption, could be solid waste subject to a RCRA “imminent endangerment” citizen suit.

The ruling came in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Washington in Cmty. Assoc. for Restoration of the Environ., Inc v. Cow Palace LLC.

“The Cow Palace case is obviously an example of plaintiffs looking to other statutes,” said Ziemba, who represents dairy farms in New York and Wisconsin.

Right-to-Know Ruling

Another much more recent example of plaintiffs looking for, and finding, new federal avenues to sue under—and one that could have wide ramifications for CAFOs across the country—is an April 11 ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

The Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act, an adjunct to the federal Superfund law, mandates that industries promptly report air releases of hazardous substances, including ammonia and hydrogen sulfide.

In Waterkeeper Alliance v. EPA, the court said an EPA final rule exempting CAFOs from some federal air emission reporting requirements under the right-to-know law was unjustified.

EPA said a federal response for CAFO emissions was impractical and unlikely, but the appeals court wasn’t persuaded the risk from gases released from routine agitation of manure pits is low.

“That risk isn’t just theoretical; people have become seriously ill and even died as a result of pit agitation,” the court said of the need for emission reports.

“The D.C. Circuit decision was fantastic, and it was a long time coming,” said Heinzen, of Food & Water Watch. “This rule had been in place since 2008, and essentially the court held that Congress made it very clear that all facilities that report over a certain threshold of regulated pollutants have to report.”

The ruling, unless it is overturned on appeal, could extend beyond federal cases.

“It could definitely harm my clients because many right-to-farm laws hinge on whether a farm is operating within the constraints of the law,” said defense attorney Todd Janzen of Janzen Agricultural Law in Indianapolis.

State right-to-farm laws typically apply a who-was-there-first rule, and protect a farm from nuisance liability if it lawfully operated for more than a year and wasn’t considered a nuisance when it began.

“If you suddenly have a court ruling that says that many farms are not complying with the law because they’re not doing air emission reporting, that could potentially impact right-to-farm act defenses,” Janzen said.

Nuisance Suits Surge

Regardless of environmentalists’ recent victories under the right-to-know law and RCRA, state-law nuisance claims, not federal environmental actions, are the bread-and-butter of most CAFO cases, some of the lawyers said.

“What I’ve typically seen is a common law civil nuisance approach to challenging CAFOs, or challenging them at a local level, such as through zoning hearings,” said Janzen.

Some suits, premised on laws that redress odor and other intrusions on private property, have hit pay dirt even in very farm-friendly places. Families living in Missouri, for example, won an $11 million verdict in 2010 over years of noxious odors from a nearby hog farm.

Despite that and similar big ticket awards, more recent trends call into question the sympathy juries in agricultural communities may have for farm odor complaints.

A spate of nuisance suits filed against Iowa feedlots led to at least one defense verdict in 2016, and similar suits in Indiana were dismissed for lack of evidence that a CAFO had been negligently operated.

But many cases are still pending, including dozens on a mass tort docket in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina, where wholly-owned subsidiaries of Smithfield Foods are among the defendants.

Residents claim local hog farms are negligently operated and a nuisance, according to court records.

There’s irony in the nuisance suit surge, according to Jonathan Lovvorn, a senior attorney at the U.S. Humane Society in Washington.

“Prior to 1970, if you had a major pollution source, whether it was a cannery, a chemical smelter or even a factory farm, your primary remedy was civil nuisance,” Lovvorn said.

Exemptions and enforcement problems with both the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act have turned the clock back, he said.

“The net result of this is that this suite of remedies, which was supposed to be a major upgrade from 1960s nuisance law, has now become less effective and less used than traditional nuisance,” Lovvorn said.

Plucking Legislative Nerves

Suits against CAFOs have struck a legislative chord in some states, where new bills would apply damages caps in farm nuisance cases and require that plaintiffs foot the legal bills if they lose.

Iowa enacted such a law in March, limiting damages to the decrease in fair market value of a property plus proven damages, and a similar bill is pending in the North Carolina legislature.

Congress has also been stirred by the litigation. The Cow Palace ruling caught the attention of Rep. Dan Newhouse (R-Wash.), who introduced legislation to “clarify the citizen suit provisions” of RCRA.

The Farm Regulatory Certainty Act, H.R. 848, would amend the federal statute to make clear it doesn’t govern animal or crop waste from farms.

“Continued judicial misinterpretation” of RCRA “could pose a very real threat to the vitality of the Nation’s agricultural community, which would lead to serious disruptions in the food supply,” the bill says.

Climate Change Ahead?

Lawyers on both sides predict more CAFOs—and more litigation—regardless of regulatory vacuums and new laws intended to corral farm litigation.

“It is worrisome when you see cases like the Cow Palace case or the D.C. Circuit case, where it looks like environmental activist groups are able to chip away at long-standing exemptions that agriculture has had under federal environmental statutes,” Janzen, the defense lawyer, said.

“I see EPA cutbacks as putting a greater burden on state and local governments to regulate CAFOs, but I don’t think you’ll see a huge decrease in CAFO regulation,” he said.

And Lovvorn, of the Humane Society, said he sees a new trend in the making, one that may eclipse current litigation themes.

This one, he said, is buoyed by the greenhouse effect of methane gases released from confined animals.

“I personally think the issue of climate change and CAFOs is going to become the most important issue, potentially overshadowing conventional air and water pollution issues,” Lovvorn said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Steven M. Sellers in Washington at ssellers@bna.com

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Steven Patrick at spatrick@bna.com