Another Market Descends Into Chaos: “It’s Madness. The Market Makes Major Moves For No Reason”

Another Market Descends Into Chaos: "It’s Madness. The Market Makes Major Moves For No Reason"

by Tyler Durden

Aug 18, 2016 6:34 PM

While that is indeed the quoted lament of a living, breathing market participant, it does not refer to what takes place in the stock or – increasingly more often – the bond or FX market. Instead, what Blake Alberts, cited by the WSJ, is furious about are the wild swings in the cattle futures market, which as a result of its recent unprecedented moves, has been dubbed “the meat casino” by traders.

In response, the WSJ writes, the world’s largest futures exchange has refused to list new contracts, leaving ranchers with fewer tools to hedge the $10.9 billion market. The reason is one painfully familiar to traders across all other product segments: a lack of collateral, only in the case of physical cattle it is much worse. According to the CME Group trading of physical cattle has become so scant that the futures market can’t get the signals it needs to set prices.

While we have long expected market-moving disconnects between a rapidly shrinking collateral base, and an exponentially growing universe of derivatives referencing this shrinking pool of underlying securities, we did not anticipate this would take place in this relatively quiet market.

According to the WSJ, the decision to delay new contract listings is the culmination of alarms raised by the exchange and industry groups this year that problems in the physical marketplace have affected futures—a highly unusual meltdown in a market that has attracted more speculators.

As the chart below shows, live-cattle futures climbed as high as $1.4155 a pound before free-falling to $1.1580 over seven weeks this spring. That represents a more than $10,000 drop in income for a single contract. Many producers have lost money as prices tumbled to a five-year low of $1.07525 a pound this summer.

The result: while end consumers are happy, traders are getting out of the market entirely. “Guys like me who have been around a long time aren’t putting as many positions on,” said Dan Norcini, an independent livestock-futures trader in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. “It’s just not worth the risk anymore, when there’s no rhyme or reason to these price swings.”

Norcini’s anger is understandable: speculators and hedgers everywhere demand liquid markets. When markets become illiquid, they simply stop trading and get out. That’s what is happening to beef futures.

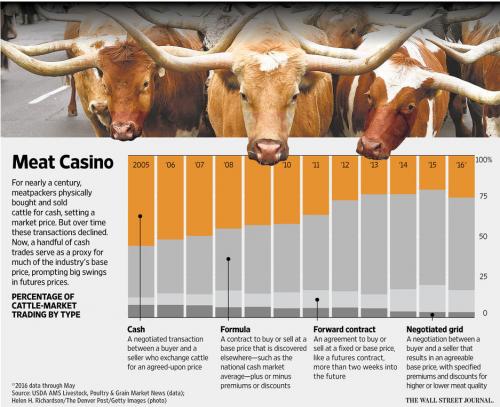

For nearly a century, meatpackers and producers would haul animals to stockyards and auction barns, to physically buy and sell thousands of cattle almost daily for cash. But over time they found it inefficient and expensive to travel miles with cattle in tow to barter over pennies and nickels per pound, so many buyers and sellers gave up negotiating each day.

The number of participants negotiating prices started to decrease in the 1980s and today, only small number of cash trades—which take place just once or twice a week—serve as a proxy for the base price used by the rest of the industry. Most of the cattle delivered to slaughter plants today are priced using a formula that incorporates the cash market value as a base, plus or minus premiums and discounts.

This means that even small trades send dramatic, widespread ripples across the entire market: "Someone sells 40 head in Iowa and it has the potential to revalue all the cattle in the nation,” Mr. Albers said. The deals that do take place between cash market buyers and sellers frequently end up being completed on Friday after the 2:05 p.m. ET close of the futures market. That means financial traders spend most of the week with limited up-to-date data.

As a result cattle traders are forced to deal with a problem most equity traders face every day: “There is very little underlying information to use,” said David Lehman, CME’s managing director of commodity research.

The CME has listed only one live-cattle contract since March and it is set to expire in October 2017. The CME has formed a working group with cattlemen to discuss fixes, including ways to increase the number of cash traders. The exchange shortened trading hours for the livestock futures contracts in February to confine market activity to the daytime, when liquidity is higher, after ranchers complained that speculators had too great an impact on prices in the evening trading.

And in a world when fundamental analysis – and information – are no longer a key driver to decision making, it means that momentum and speed-driven strategies flourish.

Enter the High Frequency Traders.

Some in the cattle industry blame high-frequency traders who can place or receive orders more quickly, and with more money, than bona fide commercial hedgers—often located in rural ranching communities.

Of course, the CME here falls back to the oldest lie in the book, namely that opening up the market to "algorithmic traders, adds liquidity to products like cattle futures, which tend to be more thinly traded than gold or oil."

Frustrated traders, and pretty much everyone else, disasgrees.

Steve Sunderman, a partner at a feedlot in Norfolk, Nebraska, recalls to the WSJ how he was watching cattle futures prices earlier this year rise and fall by more than one cent in just 15 minutes, unprecedented leaps in a market more accustomed to daily moves of fractions of a penny. The swings made him uneasy about locking in a hedge for his cattle on a Friday, when prices had climbed over $1.15 a pound only to settle at $1.12975, thinking the market would likely climb further.

“You lose confidence in your decision,” he said.

However, to HFTs who are delighted to "decide" to buy or sell – as long as they see orders they can frontrun on either side of the NBBO – the market is perfectly acceptable.

To humans, however, the cattle market has become a "meat casino" – the latest farce, broken if not by central bankers on this occasion, then by algos:

“We need to figure out why the cattle market can go from $1.30 in one week to $1.15, when we haven’t added more cattle to the marketplace,” said Ed Greiman, an Iowa farmer who sells about 100 cattle a week and is leading a cattle-marketing committee at the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association.

Some producers are trying to find their own solutions. Superior Livestock Auction LLC, an Oklahoma City-based livestock-marketing firm, piloted a video auction program to broker sales of slaughter-ready animals that would mirror sales in the cash markets, showing bids and offers in the middle of the week. Interest in streaming the auction online has been so strong that it has crashed Superior’s website in the most recent sales.

“The hope is to add a transparent venue for price discovery,” said Jordan Levi, a cattle feeder based in Oklahoma City who spearheaded the initiative. “It’s not a playground. This is U.S. agriculture, and futures should be a risk management tool.”

Ah, what a concept: a transparent venue for price discovery. To think that an entire generation of traders have lived without encountering one.

The CME, of course, promises to fix things: “Every aspect of the cattle futures contract is under review to see if there’s a way to redesign so it’s a more effective tool for risk management,” Mr. Lehman said.

We doubt it. We would be, however, interested to see how Hillary Clinton would trade in this market.

Recall, that it was Hillary’s truly unprecedented cattle futures "trading" skills that first put her on the map. As the WaPo recalls in 1994, Hillary Rodham Clinton was allowed to order 10 cattle futures contracts, normally a $12,000 investment, in her first commodity trade in 1978 although she had only $1,000 in her account at the time.

The computerized records of her trades, which the White House obtained from the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, show for the first time how she was able to turn her initial investment into $6,300 overnight. In about 10 months of trading, she made nearly $100,000, relying heavily on advice from her friend James B. Blair, an experienced futures trader. Blair was Tyson Food’s outside counsel at the time, which may have been one of the Clintons’ first case illegal outside "donations" from a third party as revealed in this fascinating story.

Cronyism and corruption aside, we can only imagine how if Hillary managed to generate a 10x return in 8 months trading cattle back in 1978, what she would do in today’s broken market.