Past, future converge in book examining strain on West’s water by Mark Arax

Candace Krebs

The Ag Journal

“As Arax writes of a childhood friend, an Armenian whose family was once neighbors to his own: “His father, mostly a gentle man, could turn fierce out of nowhere. He reserved a special anger for the thugs from Sun-Maid. To stay in business, the co-op had to sign up 85 percent of the valley’s raisin farmers. The Armenians weren’t co-op people. They were obstinate people… The Armenians were not going to be bullied, not after the Turks …”

With critical levels of drought across the West, and the threat of future water shortages looming, it might be a good time to revisit the sweeping story of how water made certain western regions what they are today, and what that might mean for the future.

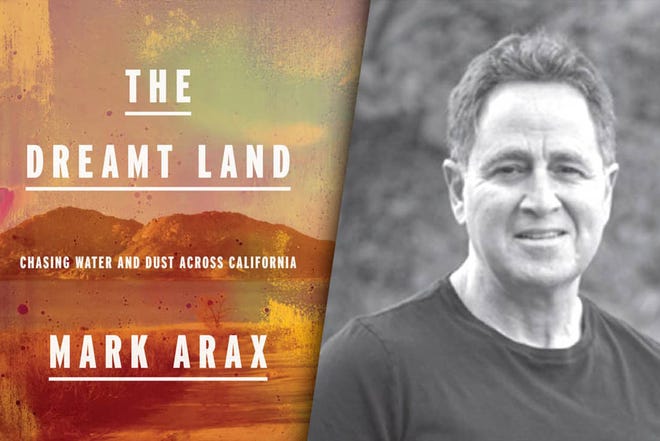

“The Dreamt Land: Chasing Water and Dust Across California,” by journalist Mark Arax, recently released in paperback, is two inches thick and exhaustive in its level of detail. But it’s worth investing the hours absorbed in tales of boom and bust to understand a place blessed with copious mountain runoff, yet otherwise sheer desert.

This contradiction is ideal, even indispensable, for growing high value crops that thrive where the days are sunny and rainless, even while the water flows. Or perhaps better put, as long as the water flows.

As Arax writes, “Drought is California; flood is California. The lie is the normal.”

The tone of this book isn’t overly sympathetic to farmers, yet the author can’t help but respect the larger-than-life quest of wrestling food and fiber from the unpredictable earth.

“The big, water-sucking corporate farmer is easy to paint from above,” he writes. “He becomes something more complicated, and compelling, on the ground.”

“It makes sense to me that the highest and best use of the land isn’t suburbia,” he adds. “One would think the question of slowing down growth might be broached. Instead, we ask communities that have existed for decades to cut their water consumption by a third so the savings can be banked, sold and shipped to some new town.”

In that way, “our rationing becomes a subsidy for the next developer,” he concludes.

For an up-close look at the implications, Arax goes to visit “Raisinland,” southeast of his hometown of Fresno, a place where Thompson seedless grapes remain an institution a century and a half after they were first introduced, though that is beginning to change.

Here, the demarcation between wealth and poverty is stark. As Arax drives the dusty back-roads, he notes drinking water fouled by gargantuan state and federal irrigation projects and the strain placed on the aquifer below, prevalent gang activity and nonexistent schools.

What he sees leads him to some intense questions. Are today’s farm workers less upwardly mobile and assimilating less readily into middle class society than their predecessors did? Is it harder for them to save up the money necessary to start or buy their own farms? Has agriculture ceased to be the stepping-stone to prosperity it once represented?

Many of the Mexican farm workers he encounters make every effort to insure their own children get good educations and never have to work a day in the fields.

Still, something about these old valley towns seems to represent the agrarian ideal.

“This is the kind of agriculture agrarian boosters envisioned for California back when the soil was being stolen by the goliaths of wheat,” he writes. (And yes, though it seems inconceivable now, the first wave of farming that occurred in Central California was wheat, followed by cotton, cheap commodities that have largely been replaced by high value fruits and nuts.)

Arax attributes the intact agrarian culture, not to the relationship of the farmer to his land or even to the water, but to his workers.

Unlike in so many other realms of endeavor, mechanical means have never been able to replace humans in the grape fields. “No machine will ever be programmed to pick bunches of grapes and lay them down on paper trays in rows between the vines,” he writes.

Hardship and opportunity

The author’s own Armenian family got its American start three generations ago working in these vineyards (in reality their grape growing experience goes back even further, at least three centuries, in their native land.) The one keepsake he treasures from his long-deceased father is the distinctively curved “girdling knife” used to cut clusters of grapes.

“Grandpa Arax used to tell me how brutally the sun in the San Joaquin Valley beat down on a man who had lost his country,” he writes of the heart-breaking choice forced upon refugees of Turkey’s Armenian genocide.

This new “promised land” was not an easy one. Of his grandfather’s earliest employer, a desperate farmer who watched raisin prices fall from $95 a ton to $20, not an uncommon occurrence, he writes, “The harvest did not go according to plan. The paper millionaire tried everything to save his ranches from foreclosure. He went from service station to service station buying old crankcase oil and threw a barrel of it down a well, trying to convince the bank that his farm sat atop an undiscovered oil field. As the bank was holding its auction to sell off his farm equipment, he flew into a rage, grabbed a hoe and severed the ear of the auctioneer. The blood did not halt the sale.”

Nevertheless, after three years working as “fruit tramps,” his grandfather and a brother saved up enough money to buy their own patch of ground near Fresno and began hiring crews to lay down grapes and tie up vines.

Despite mutual dependence, however, tensions have always simmered between farm owners and workers. Arax covers the labor strikes of the 1960s, led by iconic activists like Cesar Chavez, but also suggests a discomfort on the part of the farmers, a feeling rooted in “ah-mote,” the Armenian word for shame, over seeing immigrant laborers “brought to their knees by the urgency of the crop.”

That’s not the only source of friction.

In addition to divisions between urban and rural, and farm owners and laborers, there are rifts between the large farmers and the small ones; the conventional farmers and the environmentally sustainable ones; the farmers and the environmentalists; and even between the farmers and their own marketing co-ops.

As Arax writes of a childhood friend, an Armenian whose family was once neighbors to his own: “His father, mostly a gentle man, could turn fierce out of nowhere. He reserved a special anger for the thugs from Sun-Maid. To stay in business, the co-op had to sign up 85 percent of the valley’s raisin farmers. The Armenians weren’t co-op people. They were obstinate people… The Armenians were not going to be bullied, not after the Turks… To honor his father, Rusty has always stayed an independent raisin grower.”

Now Rusty has grown too old and weary to battle the ups and downs of a market made more volatile by imports from, of all places, Turkey.

“His son told Rusty that he needed to make a clean break and pull out the vines and plant almonds,” Arax writes. “Because the profit margins on almonds made sense. Because nuts, unlike Thompsons, could be picked by machine. Because it was time, after a century, for change.”

That same hard choice confronts countless other surrounding grape farmers.

Almonds are now undermining raisins to the point where the days of the Thompson are considered numbered. Meanwhile, the water table below has dropped at least thirty feet in just two years, a consequence of historic drought that forced the largest ranches to install expensive wells, sometimes probing 500 feet down or more, to suck out whatever water they could find to keep their trees going.

The innocuous almond, the up-and-coming pistachio and the “wonderful” health-haloed pomegranate, in Arax’s telling, have become a scourge on the region: obscenely profitable (to the tune of $80 to $125 a year from a single tree) but necessitating vast quantities of increasingly scarce water. Technology aside, nuts are the state’s latest gold rush. And in his recounting — covered earlier in the book — the original gold rush doesn’t come out looking all that golden.

So now a critical dilemma has arisen: miles and miles of tree orchards at a time when droughts are more severe, urban populations are soaring and water is literally running out.

Similarly troubling outlooks face many rural areas across the West, including the drought-stressed San Luis Valley in Southern Colorado and the High Plains that overlie the dwindling Ogallala Aquifer, as well other crisis spots around the world.

What happens when, as Arax quotes an Armenian proverb, “The water goes, but the sand stays?”

For many rural residents of California’s central valleys, such a fate is becoming all too real. Arax doesn’t offer any easy answers, but he does share a comprehensive chronicle of the past, which points to a complicated future.