USA Today: A week before Trump’s order protecting meat plants, industry sent draft language to feds

A week before Trump’s order protecting meat plants, industry sent draft language to feds

Sky Chadde, Kyle Bagenstose and Rachel Axon

USA TODAY

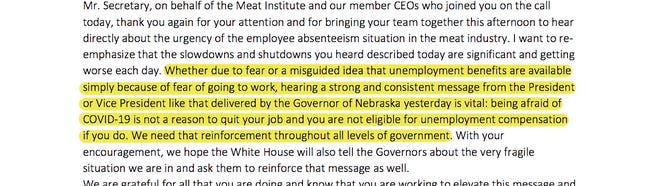

Even as thousands of their employees fell ill with COVID-19, meatpacking executives pressured federal regulators to help keep their plants open, according to a trove of emails obtained by USA TODAY.

The emails show how a major meatpacking trade group, the North American Meat Institute, provided the U.S. Department of Agriculture with a draft version of an executive order that would allow plants to remain open. A week later, President Donald Trump signed an order with similar language, which caused confusion over whether local health authorities could close plants during COVID-19 outbreaks.

The companies and their trade organizations tried to thwart health departments’ orders to close plants by asking the USDA to intervene.

“The industry ran to the White House as meat and poultry workers all across the country were getting sick and dying to say, ‘Let us stay open and have USDA intimidate health departments, so they can’t close us down because our profits are more important than workers’ health and communities’ health,’” said Debbie Berkowitz, who spent six years as chief of staff and senior policy adviser at the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and is director of the National Employment Law Project’s worker health and safety program.

The emails were obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request by Public Citizen and American Oversight and shared with USA TODAY and the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. ProPublica, which also requested the emails from the USDA, first reported on the contents Monday afternoon.

Adam Pulver, a Public Citizen attorney, said the “degree of collaboration” between Trump administration officials and industry in the emails is “astounding.”

“As outbreaks continue to emerge in meatpacking plants, it is stunning to see the cavalier attitude officials took to the health and safety of workers in the early part of the pandemic,” he said.

Julie Ann Potts, president and CEO of the North American Meat Institute, said her group and many other trade organizations “routinely suggest legislative language.”

“The Meat Institute was working with numerous federal agencies to help obtain PPE (personal protective equipment) and testing for employees, to ensure meat and poultry could be diverted from food service channels to meet retail demand, and to serve as a liaison between the government and the industry on many other issues during the crisis,” she said in a statement.

A White House spokesperson said to contact the USDA, which did not respond to a request for comment Monday.

At least 39,000 positive COVID-19 cases have been tied to meatpacking plants, and at least 184 workers have died, according to tracking by the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting.

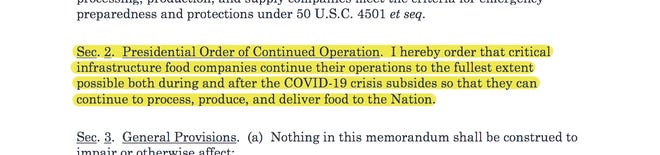

The draft executive order the Meat Institute gave the USDA in April includes language that would have directly ordered plants to “continue their operations to the fullest extent possible.”

The order Trump signed April 28, did not include that language. Instead, Trump granted Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue the authority to use the Defense Production Act to keep meatpacking plants open. Some companies interpreted that as the federal government helping them acquire protective gear.

Other language in the draft is similar to what was published a week later.

The draft order reads, “Since then, we have seen some of these operations reduce their capacity and output due to issues related to COVID- 19.”

The president’s executive order reads, “However, outbreaks of COVID-19 among workers at some processing facilities have led to the reduction in some of those facilities’ production capacity.”

Experts said the records showed that workers – the people most affected by the virus – were not consulted.

An industry approaching a federal agency with a draft regulation or other policy isn’t unusual, said James Brudney, a professor at Fordham Law School and former chief counsel of the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Labor.

But proposed regulations are vetted in a more public setting than executive orders. It is strange, he said, how quickly the draft executive order seemed to move without input from other stakeholders in and outside government.

“Wealthy interest groups lobby decision makers in Washington all the time,” he said. “They might get a draft from industry, but it wouldn’t just sail through because there would be other parties involved. That seems not to have happened here.”

Repeated requests from Smithfield

Officials at Smithfield Foods, among the largest U.S. meatpackers, sent frequent emails in May to USDA officials asking for help to reopen its plants.

Smithfield closed its Sioux Falls, South Dakota, plant April 12 after more than 350 employees tested positive for COVID-19.

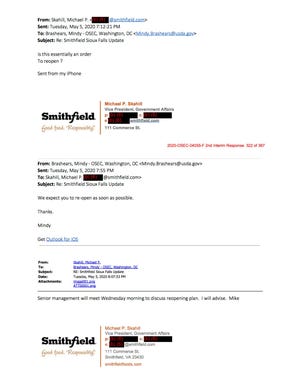

Three weeks later, Smithfield’s Vice President of Government Affairs Michael Skahill asked the USDA for a direct order to reopen the plant. The request was sent in an email May 4 to USDA Undersecretary for Food Safety Mindy Brashears and Chief of Staff to the Secretary of Agriculture Joby Young.

Skahill told Brashears and Young in a separate email that the company was in compliance with CDC and OSHA guidelines for operating a plant safely.

Brashears responded that the USDA received notice the plant was in compliance and said it could reopen.

“Is this essentially an order to reopen?” Skahill asked.

“We expect you to re-open as soon as possible,” Brashears replied.

On May 6, Brashears emailed other Smithfield executives that the USDA expected the plant to resume operations “immediately.”

The Sioux Falls plant reopened the next day.

Brashears and Young didn’t respond to an email requesting comment Monday. Smithfield spokeswoman Keira Lombardo emailed the following response Tuesday:

"We are a leading American agriculture company. Considering that fact, why wouldn’t we engage with the United States Department of Agriculture amid an unprecedented pandemic?"

About 1,300 workers at the Sioux Falls plant have tested positive for COVID-19, and four have died. On Sept. 10, the U.S. Department of Labor fined Smithfield about $13,000 for failing to protect workers.

Smithfield asked the USDA for help reopening another plant in Illinois.

On April 24, the Kane County Health Department ordered the plant to close to improve safety measures. According to the Chicago Tribune, there had been several complaints about the plant before it was ordered closed.

On May 6, the same day the USDA ordered Smithfield’s Sioux Falls plant reopened, the company asked the USDA to “referee” its talks with the Health Department.

It’s unclear from the emails what happened, but on May 8, a Smithfield executive emailed Brashears and other USDA officials to say:

“Thank you for all your support today with the Smithfield St. Charles Kane County issue. I think we have a resolution that will allow us to process next week and put protein on America’s table.”

The plant employs about 300 people, and three workers have died there, according to WBEZ Chicago.

Lawrence Gostin, a Georgetown professor and director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Center on National and Global Health Law, said having a government body intervene on behalf of a company is “outrageous.”

“To have government regulatory agencies intervene in a public health matter on behalf of a business interest is appalling,” he said. “As a result, people die. It’s not just an ethical breach or something that’s a sterile issue of good governance, which it is. It also costs people’s lives, and that’s unforgivable.”

Line speeds increased

Emails show that the National Chicken Council, which represents poultry plants, appealed to high-level USDA officials to remove limits on how fast plants run their cutting lines.

In April, before dozens of plants closed because of COVID-19, the USDA allowed 15 plants – more than the agency had ever approved in a single month – to operate at faster line speeds. At least six of the plants with waivers have had COVID-19 outbreaks.

Speeding up the lines where workers cut chicken typically leads to more crowding, according to a Government Accountability Report in 2016, a dangerous situation when confronting COVID-19.

In late April, the Chicken Council emailed Brashears to ask for her help on another matter: overturning a local agency’s decision to test all workers at a few plants. The names of the health department and the plants are redacted in the emails.

If all workers were tested, many would come back positive and the plants would not be able to operate for at least a week, according to the email.

The health department “is requiring 100% testing of all employees regardless if they are symptomatic or not. This is a decision that we have been unable to change,” the email reads.

Chicken Council spokesman Tom Super told USA TODAY the council fought the agency’s decision to test all workers because the CDC has never recommended that measure.

Industry leader Tyson Foods tested all of its workers at several plants over the summer.

"The message to workers and the communities is, ‘We’re throwing you under the bus, and we don’t really care about containing this disease,’” Berkowitz said about the contents of the emails. “It sends a green light to the industry, ‘Just continue the way you’re doing it.’”

This story is a collaboration between USA TODAY and the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. The center is an independent, nonprofit newsroom based in Illinois offering investigative and enterprise coverage of agribusiness, Big Ag and related issues. Gannett funds a fellowship at the center for expanded coverage of agribusiness and its impact on communities.