The Journal: In dealing with the Ogallala Aquifer, western Kansas is running out of water and time

by: Karen Dillon

In western Kansas, painful losses feel increasingly imminent. There’s literal loss – the essentially irreversible depletion of Ogallala Aquifer groundwater after the large-scale pumping of it to irrigate crops in recent decades. But there are also the economic losses that might follow and hurt more and more farmers, their families, businesses and communities across the region in the decades to come.

Approaches to dealing with that pain strongly diverge. Some want to avert loss by transferring water from elsewhere, maintaining an economic system and a way of life. Others want to manage it by imposing pumping limits that might extend the life of the aquifer but could also make thriving more challenging for farmers in the near-term. Still others seem to prefer to defer any pain by simply making the best use of the groundwater that’s left.

How do the people of Kansas decide which route to take? That’s where things get even more complicated. There’s nearly as much disagreement about how to respond to the situation as there is about what to do in response. While one portion of the region has made progress in setting water use limits, another is struggling to gain support for any alternative to the status quo. State officials are encouraging change, but they’re certainly not trying to mandate it. Irrigators on different sides of the divide increasingly find themselves in conflict.

This is hardly a new phenomenon.

As Kansans, we’ve always fought about water. We’ve fought about irrigation ditches, water wells, storm runoff, tailwater pits and oilfield pollution. We’ll fight for water for creatures great and small, from whooping cranes to small minnows. As Colorado and Nebraska can attest, we’ll fight over water we only wish we had.

Between rounds, we’ve built Wichita’s Big Ditch for flood control, survived the Big Dam Foolishness controversy over Tuttle Creek Dam and turned Greensburg’s Big Well into a tourist attraction. For the bare-knuckle variety of these fights, no area of the state holds more potential than the west, where the Ogallala Aquifer was tapped to make up for a lack of rainfall. It’s a resource that not only has transformed western Kansas agriculture, but it’s also altered the state’s political and financial landscapes.

The Ogallala may be huge, but its capacity is finite. For decades, decision-makers in Topeka had some ideas about how to manage the aquifer, but those thoughts all had one thing in common: To make the water last longer – and avoid economic calamity – someone would have to agree to pump less and take the economichit. Few rushed to volunteer.

But the passage of time has changed some outlooks, redrawing battle lines.

Instead of just fighting over who gets to use water, we’re increasingly in conflict over who doesn’t get to use it and who decides that. Throughout western Kansas, some of the state’s largest irrigators, with help from a 2012 law that allows the establishment of local limits through Local Enhanced Management Areas (LEMAs) within Groundwater Management Districts, are pushing for significant reductions in the amount of water being drawn from the Ogallala and getting pushback from neighboring irrigators who either don’t want to limit themselves or don’t like the terms of how they’re being limited.

Trying to forge agreement on limits is difficult, even though the system already privileges some users over others.

Water is allocated based on whoever started using it first, with later users – who have junior water rights – having to stand in line behind senior water right holders, who get their allocation of the water first. (Hence the phrase, “first in time, first in right.”)

It’s a simple concept that we’re all familiar with. For instance, if you’re among the first standing in line to buy tickets to a film or a concert, you’d be upset if somebody who came after you cut in line and bought the seats you were hoping to purchase. Water law works similarly – it doesn’t guarantee the right to a ticket, only the chance to use one if it is still available by the time you reach the front of the line.

But when it comes to Ogallala groundwater, the tickets never sell out, at least in the short term. The wells of junior water rights holders are hardly ever shut down to protect senior wells from impairment. That’s because the painful effects of scarcity aren’t felt immediately when you’re mining water from below as they are when, say, a drought reduces the flow of water that can be used for irrigation from the surface. As a result, the Ogallala has become a giant drink with too many straws. It can’t support all users at their present levels forever.

Theoretically, the problem might be less severe if senior water right holders fought to reduce the number of straws affecting what they can draw. But when they’ve tried to assert their place in line, it can get ugly. Just ask Garetson Bros. of Haskell County, who faced backlash from neighbors and a five-year legal battle over impairment of its senior water right by two junior rights. What’s defensible under the law isn’t always easy to enforce or likely to win allies.

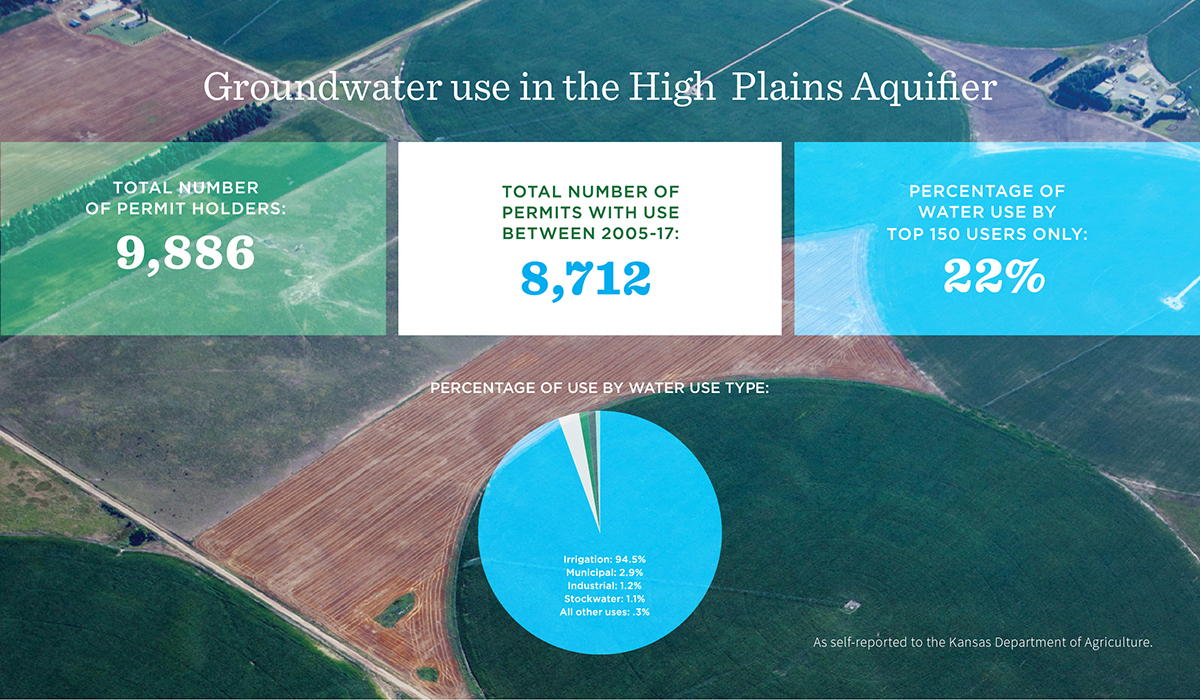

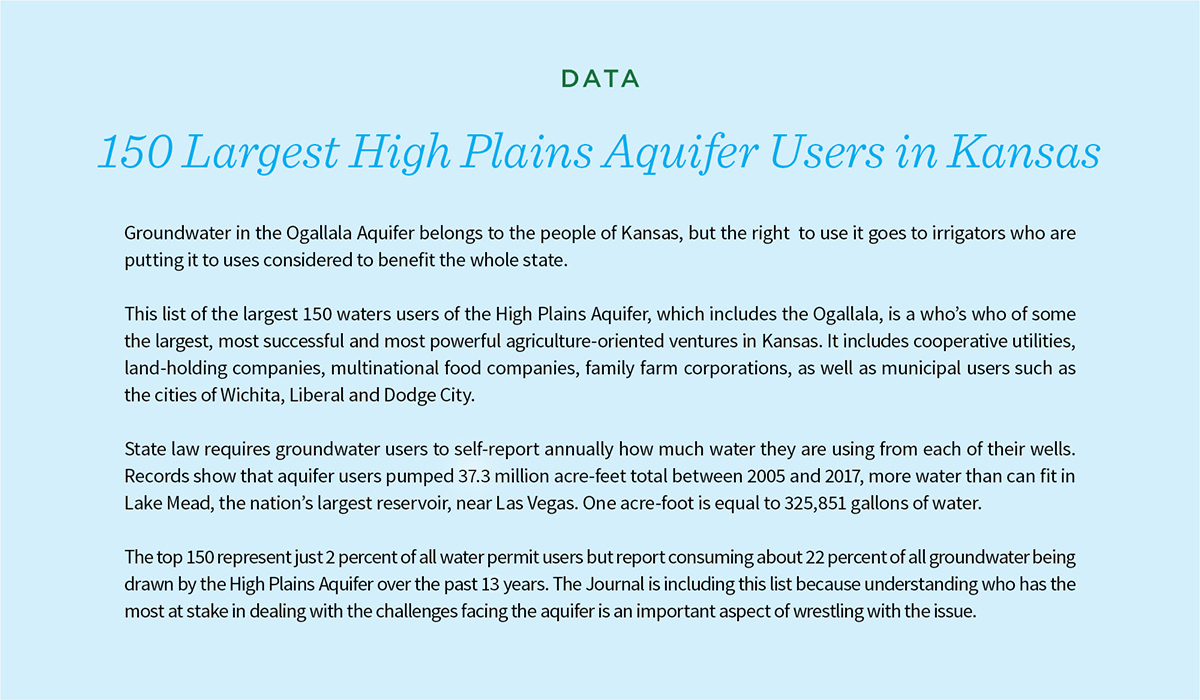

Annual use of the High Plains Aquifer, which includes the Ogallala, fluctuates widely from year to year, often based on whether farmers receive a lot of rainfall or suffer through a drought. And while irrigation statewide peaked in the 1980s, aquifer users still pumped 37.3 million acre-feet or an average of 2.9 million acre-feet per year, between 2005 and 2017, according to state records. The 37.3 million figure is more water than can fit in Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir, near Las Vegas.

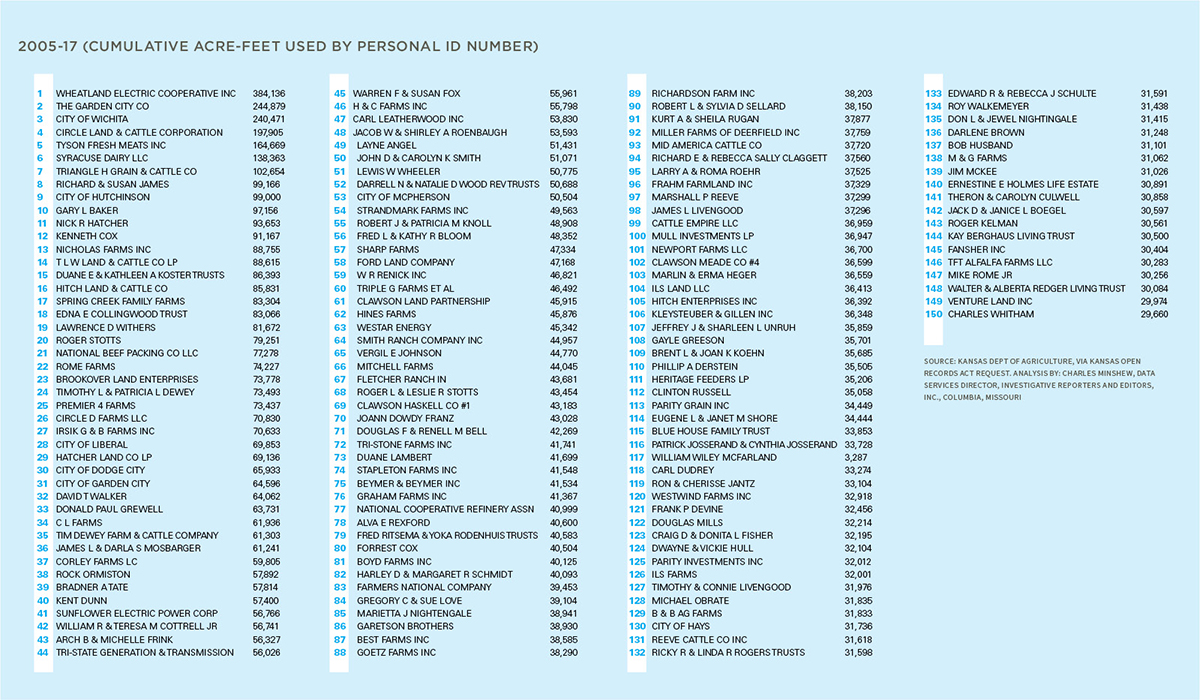

Furthermore, as groundwater gets scarcer, its use is becoming ever more concentrated among fewer and fewer irrigators. Analyses of state reports show the top 150 users consumed about 22 percent of all groundwater drawn from the High Plains Aquifer over the past 12 years. The average user in the top 2 percent withdrew 4,232 acre-feet, enough to cover more than 3,100 football fields in a foot of water. The remaining 98 percent of users report consuming just a fraction of that, an average of about 230 acre-feet per year.

But to understand how we got here – and where we might be going – it helps to rewind to last summer, when the future of water in western Kansas became the centerpiece of a tour being led by then-Gov. Sam Brownback.

CHAPTER ONE

With an eye on rallying more western Kansas farmers to get on board with conserving water, Brownback (with Jeff Colyer, then the lieutenant governor and now the governor, in tow) touted a scientific study showing that the Ogallala could be preserved with far smaller reductions in water use than previously thought. Think just 25 percent to 45 percent rather than draconian cuts of 75 percent or more.

For Brownback, who four years before had made it a goal of his administration to develop a 50-year plan for the management of the state’s water, it was a finding worthy of celebration. “Phenomenal news: the Ogallala Aquifer is recharging faster than we previously realized,” he wrote on his Facebook page, echoing his in-person sentiments. “Sustainable use of the Aquifer is attainable.”

The boldness of Brownback’s pronouncement was more than counterbalanced by the ground-level political implications involved in turning such a vision into reality.

That goal for now depends on irrigators to do the painful work of imposing limits on themselves in small geographical areas. By avoiding any heavy-handedness from Topeka, state officials have pinned their hopes for the aquifer’s future on creating a critical mass of egalitarian-minded volunteers.

It’s a give-the-work-back approach that has one significant success story so far. A 99-square- mile area in portions of Sheridan and Thomas counties saw water users achieve a 35 percent reduction on average from 2013 through 2016, slowing the aquifer’s rate of depletion from 2 feet to 5 inches per year with the help of above average rainfall. Earlier this year, a plan was approved to expand that Local Enhanced Management Area to all 3 million-plus acres of Northwest Kansas Groundwater District No. 4. But it didn’t come without a years long fight that continues in court.

The very mention of stricter limits, even when they are locally imposed, provokes difficult and uncomfortable dialogue among irrigators. For any farmer, water is a necessity. When crops are good and prices are high, lenders get paid, help is hired, implements and vehicles are bought, communities thrive.

A debate over locally imposed water-use limits in northern Finney County illustrated the dilemma all too well. Irrigators at a February meeting of Groundwater Management District No. 3, one of the state’s most groundwater-depleted regions, expressed reservations about conserving because they were afraid they would suffer more pain than their neighbors. Some contended that all users should suffer equally, a complicated task considering that a growing number of farmers are making do with little or no irrigation water and thus have very little to sacrifice.

Others who had cut back on groundwater use in recent years worried they wouldn’t be rewarded for their past conservation while those who continued pumping their full allotments would get credit for conservation going forward.

Even Brownback himself contributed to feelings of resentment. On last summer’s tour through western Kansas, Brownback reportedly mentioned how he felt like a “cattle rustler” by recruiting dairies to the state. The fact that Brownback was willing to push for conservation among farmers at the same time that he was assuring dairies that Kansas had enough water for them to relocate seemed two-faced to some in District No. 3. While it’s not unusual for state officials to push to use water for agricultural products that can be sold at higher prices than grains, the comments left the impression that irrigators were being asked to sacrifice for the economic benefit of others.

The messiness of the conversation that day in District No. 3 wound up killing any discussion of mandatory limits on groundwater use in part of Finney County. District officials expressed support for irrigators pursuing voluntary limits over a much smaller area, making conservation efforts more palatable but also much less comprehensive. While an increasing number of farmers may be willing to admit there’s a growing sense of urgency to reduce water use, it can be offset by a reluctance to wind up as the biggest loser. No one wants to suffer while those around them prosper with less sacrifice.

CHAPTER TWO

Caring for western Kansas’ Ogallala Aquifer with replenishment off the table

From the time Brownback took office in 2011 until he left in 2018, preserving the aquifer, which stretches across parts of eight states and underlies 174,000 square miles of the Great Plains, had been one of his most talked about priorities.

And little wonder. The water deposited at the end of the last Ice Age about 12,000 years ago is, in a sense, liquid gold. Irrigated cropland across the region is a linchpin of a multibillion-dollar agricultural economy that produces grain, biofuels and feed for cattle that wind up as burgers and steaks being served well beyond Kansas.

Corn is hardly the only crop being grown, but irrigated corn offers great potential for high net returns. Altogether, state officials say, corn and beef production alone fed by the aquifer employ more than 56,000 people and add $3.2 billion to the Kansas economy, amounting to 4.3 percent of its jobs and 10 percent of the economy. While Kansas would suffer mightily if the current systemcollapsed, a couple of factors have worked againsta solution. First, it’s a slow-motion crisis. It’s easy for more pressing issues to gain precedence. Second, there’s no political solution that does not involve pain that would be dished out widely.

When farmers first reached the High Plains in the 19th century and into the 20th, they used wooden windmills that could bring 10 gallons of water a minute to the surface.

But after World War II and the advent of improved pumps and center pivot irrigation systems, farmers became miners of the water, extracting it from its dark bed of sand, silt, clay and gravel at what seemed like a speed-of-light rate of 200 gallons to 1,000 gallons or more per minute.

There was such an abundance of water in the Ogallala that conservation was an afterthought. In a sense, farmers had thwarted their most tenacious adversary: the weather. The swish-swish of the sprinklers brought a sense of comfort and tranquility as they used trillions of gallons of water.

Last summer, Dwane Roth, who farms in Finney County, conducted a water study in conjunction with Kansas State University in which he produced higher quality yields of corn while using far less water than other nearby farms.

“It’s like a sense of security,” says Dwane Roth, who farms in Finney County. “If you leave the pivot on, you think, ‘I’m going to obtain these bigger yields.’”

Even as the water poured out of the pivots, the state kept handing out permits to drill more and more wells – overappropriation that would make subsequent efforts at conservation even more difficult as wells dry up.

The combination of more wells pumping more water meant higher crop yields, and the Ogallala Aquifer grew in importance, currently supplying 70 percent to 80 percent of the water used by Kansans to support municipalities in the region, industry, and agriculture.

Thirty percent of the water in the High Plains Aquifer has been pumped, according to a 2013 article in PNAS, the official scientific journal of the National Academy of Sciences. An increasing number of wells are becoming useless for large-scale irrigation. In places, the depth to water has dropped more than 150 feet.

In hopes of riding to the rescue, Brownback and the Legislature pushed through a slew of water laws the session after he took office with the goal of altering the aquifer’s trajectory. They are essentially based on the concept that farmers would choose to conserve water to save the family farms for their children and grandchildren and make do with less income.

The new laws did usher in changes that Brownback hailed as significant. Lawmakers did away with the “use it or lose it” concept in areas that no longer had water supplies for new water rights. “Use it or lose it” was seen by supporters as a disincentive to conservation. The state several years earlier had set a limit of 24 inches of irrigation water per acre. But still, if the farmer did not use any water for five straight years, the state could, in theory at least, declare the water right to be forfeited. So farmers, it was thought, had a perverse incentive to pump even when they did not need to do so. Although almost no water rights are declared forfeited, Brownback believed the forfeiture law needed to be changed anyway.

Another water-saving measure was the ability to create Local Enhanced Management Areas that would crimp the amount irrigators could pump. The limits are chosen by a regional board but enforced by the chief engineer of the Kansas Division of Water Resources. The idea originated out of Northwest Kansas Groundwater Management District No. 4, where its longtime director, the now-retired Wayne Bossert, and his board championed the idea. Brownback signed legislation creating the zones in 2012 with the hope of encouraging farmers to reduce water use by about 20 percent, thereby extending the life of the aquifer.

But to do so, farmers would have to risk their financial footing for a rather ambiguous payoff – a longer life, usually unspecified, for a resource that for all practical purposes is not renewable.

Jim Butler, senior scientist and geohydrology section chief at the Kansas Geological Survey, says a reduction in pumping can have a big impact, but the aquifer will never be restored to its predevelopment levels.

“In an ideal world, maybe you can stabilize the aquifer, but reducing pumping would certainly diminish the rate of decline,” Butler says. “Replenishment of the aquifer is really not in the cards.”

CHAPTER THREE

The iWOB – off-center wobbling diffuser sprinkler – is designed to deliver consistent droplet size and uniformity at relatively low water pressure. It’s a far cry from the impact sprinklers that were common on early center pivot systems.

Finney County farmer an example of finding success watering with less

In an interview, Brownback characterized the depletion of the aquifer as a “tragedy of the commons.” Tragedy of the commons is an economic theory that describes “a problem that occurs when individuals exploit a shared resource to the extent that demand overwhelms supply, and the resource becomes unavailable to some or all,” according to an oft-cited 1968 article in the journal Science.

“We have been over-irrigating,” Brownback said in an interview last year. “It just makes you cry now because you would rather have the water in the ground than have lost it. … These are hard decisions, and the water under (the farmers) is all they have, but they control their own destiny.”

Among those trying to change the trajectory of the situation are Roth, who in addition to farming is the owner of a water technology farm near Holcomb, and Troy Dumler, the vice president and general manager of a land-holding business called The Garden City Co. Both were in the room last summer when Brownback and Colyer visited.

Roth is one of the leading innovators striving to extend the life of the aquifer, and Dumler oversees the second-largest consumer of Ogallala groundwater in Kansas. According to state records, The Garden City Co. used more than 244,879 acre-feet of water between 2005 and 2017, roughly the equivalent of the water presently in storage at Tuttle Creek Lake at the start of 2018.

Roth, Dumler and a small group of farmers led the charge in Kearny and Finney counties to develop a plan to restrict water use.

“Our well capacity has declined significantly,” says Dumler. “We are trying to do something that conserves and extends the life of the aquifer for the land we own, and at the same time,conserve our profitability. It’s trying to find that sweet spot between those two goals.”

Corn and beef production alone fed by the Ogallala Aquifer employ more than 56,000 people and add $3.2 billion to the Kansas economy, amounting to 4.3 percent of its jobs and 10 percent of the economy.

Although a board was created to oversee the process and hold public meetings, strong opposition undercut the push. A couple of farmers said that such an agreement with the government was “socialism,” according to the meeting’s minutes.

The freedom to use the maximum amount of water permitted by a water right is so deeply ingrained that many are reluctant to give it up. “The answer you get from some people is, ‘It’s my water right, and I’m going to do what I want with it,’” says Roth, who owns land and also leases some land from the Garden City Co.

Roth is not one of those farmers. He’s pushing a combination of adaptive and technical approaches to extending the life of the aquifer, both through limits that call for using less water and through innovations that might allow farmers to grow more with less.

Last summer, he conducted a water study in conjunction with Kansas State University. Roth has placed soil monitors on his farmland thatlet him know what the moisture level is at any time, day or night.

The moisture probes connect electronically with an app on his iPhone and send alerts when plants need watering. Sometimes those alerts can occur at 2 a.m., and “you have to get up, go out and turn on the pivots,” Roth says.

The results of the study came in after harvest, and it was good news.

Roth says he watered his study area only 5.5 inches throughout the summer. His cousin used 16 inches of water, and another farmer used 14.8 inches.

But Roth harvested 241 bushels of corn per acre and the other men got 233 bushels.

“What we have found is that we are overwatering, not by a little bit, but by a lot,” Roth says.

CHAPTER FOUR

Politics, economics complicating efforts to stem Ogallala groundwater depletion

For the unitiated, the appearance of a no-till field is a clear departure from using tilling practices to keep weeds at bay. Crop residue on the surface can reduce erosion and improve soil tilth.

In recent decades, state law has required farmers to self-report annually how much water they are using from each of their wells. The statistics provide the clearest publicly available picture about use of the Ogallala.

The Journal, using the Kansas Open Records Act, requested spreadsheet data for all groundwater users in the High Plains Aquifer and how much water they had pumped from 2005 to 2017. Charles Minshew with the Investigative Reporters and Editors at the University of Missouri in Columbia crunched the numbers and created a list of the top users of the Ogallala Aquifer for The Journal.

The list of the largest 150 users is a who’s who of some of the largest, most successful and most powerful agriculture-oriented ventures in Kansas – cooperative utilities, land-holding companies, multinational food companies, family farm corporations – as well as municipal users such as the cities of Wichita, Liberal and Dodge City.

One of the patterns the data reveal is that some of the biggest water users in the region are leasing their land to tenant farmers, which helps underscore another of the complications in securing the aquifer’s future.

While tenant farmers may be just as likely to use the latest in water efficiency practices as farmers using their own land, it’s less clear that they and the landowners who lease to them have the same incentives or abilities to reduce water consumption over the long term through conservation measures. For instance, through Water Conservation Areas, which legally came into being in 2015, water rights holders or groups of water rights holders can voluntarily agree to restrict their own use with more flexibility.

Three of the aquifer’s largest users illustrate the potential concern, even if they don’t necessarily prove the difference.

Robert Lee of Guymon, Oklahoma, is an officer for Hitch Land & Cattle Co. It has farmland in Seward County, where Liberal is the county seat, and has tenant farmers. Its wells reportedly pumped more than 85,831 acre-feet of water, putting Hitch Land & Cattle 16th on the list of users from 2005 through 2017.

Lee wouldn’t say how much land he owned: “That’s like asking how much money you have.” He was not aware of the state’s conservation programs.

But he says generally farmers “don’t waste water like you used to. Ninety-five percent of the country has gone to sprinklers, and low ones, instead of 10 or 15 feet off the ground.”

Interestingly, two of the largest water users were Tyson Fresh Meats and Wheatland Electric Cooperative. Officials for Tyson, which came in fifth on the list as reporting 164,668 acre-feet of water use over the period, wouldn’t be interviewed but said its “tenant farmers are using best water management practices, including monitoring soil conditions before using water, having cover crops on the ground to help retain water, and using higher efficiency water application systems.”

Wheatland Electric is No. 1 on the water-use list, reporting pumping of 384,136 acre-feet of water since 2005. That’s more than the amount of water that can normally be stored in Milford Lake near Junction City.

Ray Luhman, manager of Groundwater Management District No. 4 in northwest Kansas, helped shepherd a proposal through the governmental process to expand a small Local Enhanced Management Area to one that covers the entire district.

Wheatland, a member cooperative of Sunflower Electric Power Corp., got into tenant farming about 10 years ago when Sunflower was trying to expand its coal-fired generating plant in Holcomb, says Luke West, Wheatland’s director of corporate services and water.

The corporations bought the land and the water rights to ensure that there would be enough cooling water. But the expansion never happened. So Wheatland leased land back to farmers.

West says several tenant farmers were implementing conservation methods, and Wheatland was exploring setting up a voluntary Water Conservation Area. As of The Journal’s publication deadline, its plan was seen as pending on the state Department of Agriculture’s website.

Underscoring just how difficult it can be to initiate a conversation about water use, some people simply kept their thoughts to themselves.

Tyler Hands, one of the owners of Triangle H Grain & Cattle Co., which was seventh on the water-use list, wouldn’t even broach the subject.

“I’m not interested in that story. It gets pretty political,” Hands would only say.

But the situation isn’t only about politics. It’s also about economics, and the consequences can be felt all the way down to the level of the family farm. From 2007 through 2013, farmers in Kansas experienced a period of significant profitability, making as much $50 to $100 an acre with several crops, according to Mykel Taylor, an associate professor of agricultural economics at Kansas State University.

Since 2014, returns have moved in the opposite direction, with 31 percent of farms experiencing losses in 2016 and 2017. The turn is just a reality of the cycles that can affect farming. The high profits of the late 2000s encouraged farmers around the world to grow more crops to capitalize on the boom, creating abundance that ultimatelyhelped drive down prices and profits. The downturn will ease as farms produce less and marginal land gets taken out of production. But that’s of little solace if you’re a struggling farmer right now, facing everything from the prospect of a trade war to less than ideal rainfall.

Annual living expenses each year for the average farm family ran $68,095 in 2017, making absorbing losses that can run into the tens of thousands of dollars a brutal financial blow, and of those farmers who went in the hole last year, nearly a third of them lost as much as $50,000.

While family members might get jobs off the farm to supplement their farm incomes – for many it’s already crucial, especially for benefits such as health insurance – there are only so many jobs available in rural parts of Kansas. As a result, in leaner times, how you farm becomes even more important.

“Tight margins mean that people’s resource management strategy and business strategyare crucial,” Taylor says.

In practice, the distinction between farmers with owned acreage and tenant farmers tends to be blurry rather than distinct, Taylor says.

Even farmers with owned acreage may choose to rent land to scale up and become more profitable. But those who own more of their acreage have an advantage in the sense that they don’t have to pay rent, which is particularly helpful during lean times. They keep the income off their land for their living expenses rather than having to pay a portion of it to someone else.

However, it often takes time for people to reach that level of security. Farmers with owned acreage, Taylor says, tend to be older and more established while younger farmers tend to be the ones who must rent to farm as they build their operations. But because of that, younger farmers are more at risk at being squeezed during leaner times.

Irrigation for crops can be a great equalizer in that it reduces risk. Instead of relying entirely on Mother Nature’s generosity as a dryland farmer would, access to groundwater gives farmers more control over producing yields that would keep them profitable. “The presence of water for irrigation means that they are not as susceptible to the loss of an entire crop,” Taylor says.

Modest restrictions in water use, such as the kind often proposed in LEMAs, probably don’t impact the profitability of farming much, says Taylor, because of increased water efficiency practices and other technological developments, such as more drought-resistant crops. However, using less water to get similar yields requires more effort to ensure water is used in the right amounts at the most beneficial times. And it also means there’s less margin for error if you don’t get it right.

If restrictions were taken to the extreme, they would hit areas with less annual rainfall the hardest. In parts of southwest Kansas, for instance, irrigated land is much more valuable than dryland because it’s so much more productive. Without groundwater, yields would fall and the crop mix would change, significantly changing the equation for what it takes to be profitable.

Managing editor Chris Green and copy chief Bruce Janssen contributed to this story.