New York Times: Save Our Food. Free the Seed.

By Dan Barber | June 7, 2019 Additional reporting and graphics by Ash Ngu | Photographs by Ruth Fremson

Not long ago I was sitting in a combine tractor on a 24,000-acre farm in Dazey, N.D. The expanse of the landscape — endless rows of corn and soybeans as precise as a Soviet military parade — was difficult to ignore. So were the skyscraper-tall storage silos and the phalanx of 18-wheeled trucks ready to transport the grain. And yet what held my attention were the couple of dozen seeds in my palm — the same seeds cultivated all around me.

We are told that everything begins with seed. Everything ends with it, too. As a chef I can tell you that your meal will be incalculably more delicious if I’m cooking with good ingredients. But until that afternoon I’d rarely considered how seed influences — determines, really — not only the beginning and the end of the food chain, but also every link in between.

The tens of thousands of rows surrounding me owed their brigade-like uniformity to the operating instructions embedded in the seed. That uniformity allows for large-scale monoculture, which in turn determines the size and model of the combine tractor needed to efficiently harvest such a load. (“Six hundred horsepower — needs a half-mile just to turn her around,” joked the farmer sitting next to me.) Satellite information, beamed into the tractor’s computer, makes it possible to farm such an expanse with scientific precision.

The type of seed also dictates the fertilizer, pesticide and fungicide regimen, sold by the same company as part of the package, requiring a particular planter and sprayer (40 feet and 140 feet wide, respectively) and producing a per-acre yield that is startling, and startlingly easy to predict.

It is as if the seed is a toy that comes with a mile-long list of component parts you’re required to purchase to make it function properly.

We think that the behemoths of agribusiness known as Big Food control the food system from up high — distribution, processing and the marketplace muscling everything into position. But really it is the seed that determines the system, not the other way around.

The seeds in my palm optimized the farm for large-scale machinery and chemical regimens; they reduced the need for labor; they elbowed out the competition (formally known as biodiversity). In other words, seeds are a blueprint for how we eat.

We should be alarmed by the current architects.

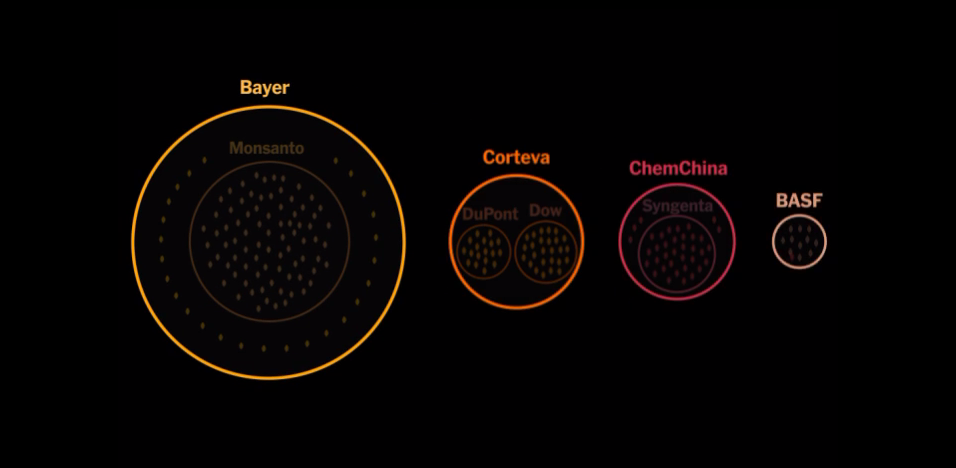

Just 50 years ago, some 1,000 small and family-owned seed companies were producing and distributing seeds in the United States; by 2009, there were fewer than 100. Thanks to a series of mergers and acquisitions over the last few years, four multinational agrochemical firms — Corteva, ChemChina, Bayer and BASF — now control over 60 percent of global seed sales.

The financial crisis brought us from boom-era complacency to nail-biting angst over institutions that were considered too big to fail. A decade wiser now, why are we not spooked by just four chemical companies largely controlling our future food supply?

Disclosure — I am a co-founder of a small seed company, so I have seed in the game. But so does anyone who cares about good food.

Flavor, long under siege, is having its moment as consumers abandon the processed foods of the center aisle in search of local and organic ingredients. Cooks have known forever that this kind of food tastes better; scientists are confirming that it’s better for the earth, too.

Organic growing reduces the use of harmful chemicals, improves the soil’s ability to sequester carbon and retain water, and strengthens biodiversity. As the climate grows more severe and unpredictable, we will need seeds adapted to this kind of farming, and to their environments — precisely what a centralized, chemical-driven industry is not built to provide.

Instead, Big Seed keeps getting bigger, doubling down on a system of monocultures and mass distribution.

The problem is not that these seed corporations are too big to fail. It’s that they are failing to deliver what growers need to grow and what we want to eat.

It’s worth noting that seed oligarchies are a relatively new thing. Scratch that. Seed companies are new.

From the Big Bang of agriculture around 10,000 B.C. until a hundred or so years ago, farmers saved their seeds to plant for the next season. Thousands of varieties evolved across the globe, constantly adapting to their environment and to the preferences of the culture and cuisine.

Nineteenth-century American farmers benefited from this diversity of vegetables, grains and fruits. It was a good time to be a seed. Not only welcomed but encouraged to stay through a government-backed seed distribution program, free seed allowed farmers to perform trial and error to see what worked.

It was a brilliant idea — except from the perspective of the nascent seed industry. Seed that was freely distributed, and freely saved and traded by farmers, stifled privatization. After decades of lobbying, the industry won (surprise!) and Congress ended the program in 1923.

Meanwhile, thousands of years of intuitive plant breeding and selection were evolving into a science. On the heels of the Austrian monk-cum-geneticist Gregor Mendel, plant breeders began making intentional crosses between plant varieties to create stable hybrid offspring.

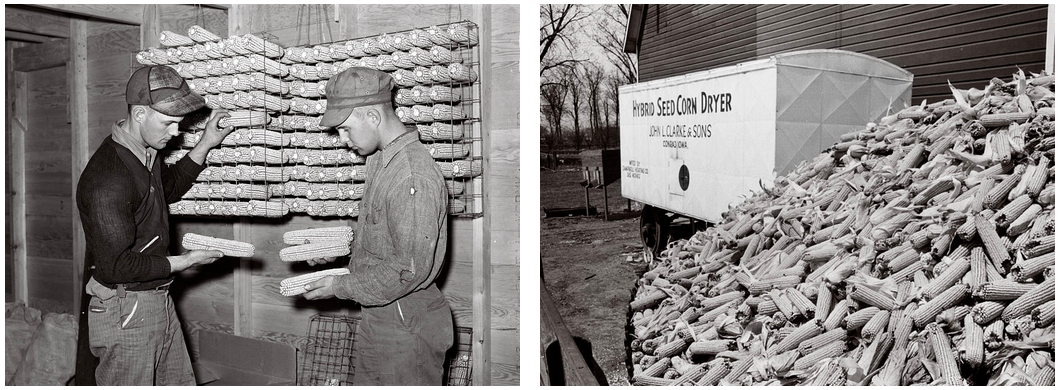

Hybrid seeds were a hit with farmers because they could provide higher-yielding and more uniform plants. And seed companies loved them because they forced farmers to buy new seed every year. (If you save seeds from hybrid plants, the next generation will not be uniform.)

The first hybrid corn became commercially available in the early 1920s. Twenty years later, nearly all of Iowa was planted with hybrid corn.

Some seed purists consider hybrids the original sin. Tempting farmers away from saving their own seed is, by their measure, directly connected to the corporate seed juggernaut we’re faced with today. Since I’m writing this while sitting next to a brigade of cooks preparing several hybrid vegetables and grains for our restaurant’s menu, I’d argue that in a fallen world, hybrids are often reliable — and, in the right breeder’s hands, delicious. It’s true, though, that hybrids displaced valuable diversity and precipitated seed privatization.

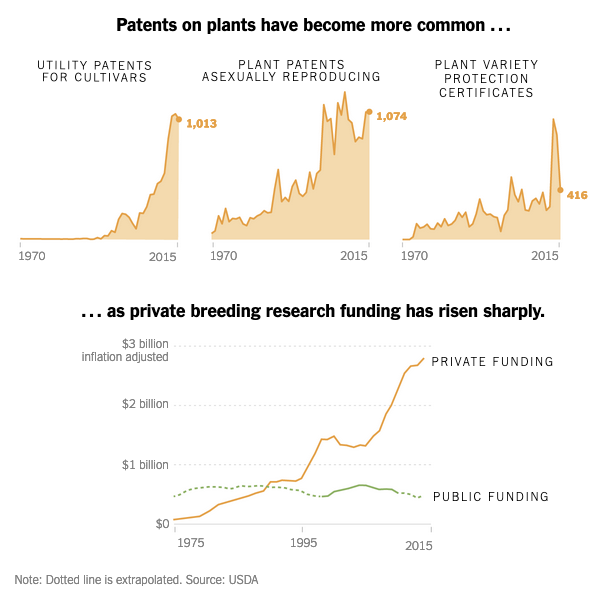

The knockout punch for farmer-controlled seed was the utility patent. In a landmark (and utterly bananas) decision in 1980, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of allowing patents on living organisms. It wasn’t long before the same protections were extended to crops. New advances in genetic engineering supported the argument, with companies claiming seeds as proprietary inventions rather than part of our shared commons. Utility patents restricted farmers’ freedom to save and exchange seed and breeders’ right to use the germplasm for research.

The slow march of seed consolidation suddenly turned into a sprint. Chemical and pharmaceutical companies with no historical interest in seed bought small regional and family-owned seed companies. Targeting cash crops like corn and soy, these companies saw seeds as part of a profitable package: They made herbicides and pesticides, and then engineered the seeds to produce crops that could survive that drench of chemicals. The same seed companies that now control more than 60 percent of seed sales also sell more than 60 percent of the pesticides. Not a bad business.

More than 90 percent of the 178 million acres of corn and soybeans planted last year in the United States were sown with genetically engineered seeds. It’s a vision as dispiriting as it is unappetizing.

Vegetables have been spared some of this genetic tinkering but are increasingly victim to the same aggressive corporate seed environment. Last year the pharmaceutical company Bayer acquired the world’s largest vegetable seed company, Monsanto.

For these megacompanies, capturing a large share of the vegetable seed market means capturing patentable genetics. Since 2001, the scope of utility patents has expanded to include novel plant traits. (Before this, you could own a variety, but not its traits, in the same way that you can own a beachfront property but not the particles of sand.)