New Food Economy: A new reorganization would change Trump’s USDA. The question is, by how much?

by H. Claire Brown | November 16th, 2017

The “People’s Department” may see its biggest reshuffling since the ’90s. A paradigm shift, in charts.

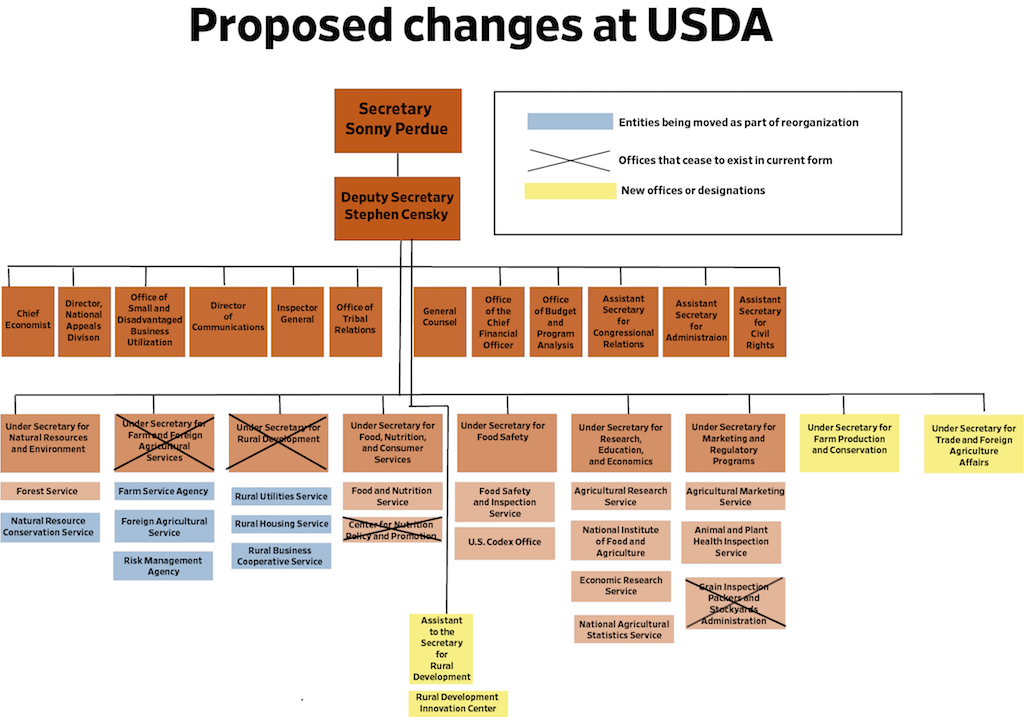

On Tuesday, Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue issued a memo furthering a reorganization proposal announced earlier this year at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). For the purpose of “improving customer service and efficiency,” the department plans to restructure a bunch of offices—including eliminating the Grain Inspection, Packers, and Stockyards Administration (GIPSA) as a standalone agency, moving the U.S. Codex, and appointing a Chief Information Officer for every mission area in the administration.

Ok, we know: That all sounds like gibberish. Is the reorg just a bureaucratic reshuffling, or do these potential changes have real implications for U.S. food production and policy?

Some of the decisions—like moving the Office of Pest Management Policy (OPMP) from under the Agricultural Research Service to the Office of the Chief Economist—probably mean very little.

“It just better aligns with other offices. It’s as simple as that. We don’t do research, and we always get people calling us about research and we just can’t even address,” says Dr. Sheryl Kunickis, OPMP’s director. She says nothing about her staff or operations will change.

But other moves have already ruffled a few feathers.

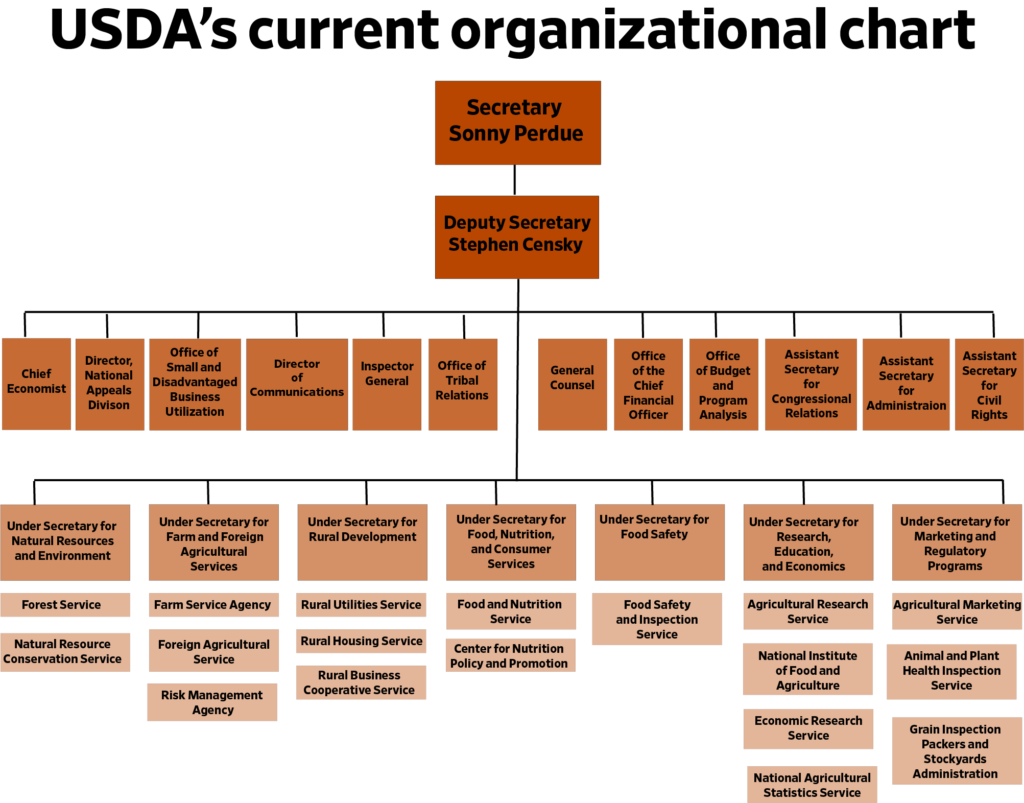

Here’s what USDA’s organization looks like before the proposed changes

For instance, advocates are sounding the alarm over the elimination of GIPSA as its own entity.

One of GIPSA’s jobs is to enforce a piece of antitrust legislation in the meat industry, but the reorganization would nest it under the Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS)—an entity that oversees promotional efforts including commodity checkoff programs. The work AMS has done with the checkoffs has been criticized for being too friendly to large meatpacking companies while small-scale producers pay the price.

There’s concern among some that the restructure would further weaken the protections GIPSA affords small farmers—continuing a trend that began when Perdue’s USDA rolled back an Obama-era rule that would’ve made it easier for contract farmers to sue big meat companies.

“To move GIPSA from a standalone agency to one under the Agriculture Marketing Service—a marketing agency, not a regulatory agency—sends the message to American livestock and poultry farmers that the Administration values the interests of corporate packers and integrators over protecting farmers,” said Paul Wolfe, senior policy analyst for the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC), in an email.

The proposed changes include eliminating GIPSA as a standalone office and getting rid of the “Rural Development” under secretary role

Small farm advocates worry the shuffle might create a wolf-in-the-hen-house-type situation: Put the regulators under the marketers’ roof, the logic goes, and regulation could take a back seat to industry promotion. Or the regulators’ jobs might slowly disappear altogether, since USDA is still in a hiring freeze and the shifts may cause current employees to leave their positions.

Perhaps more telling: The meatpacker-regulating part of GIPSA is being nestled under a newly-created Deputy Administrator for Fair Trade Practices. That office would also house other initiatives that have proven to be flashpoints in the not-so-distant past: The Country of Origin Labeling Program and the Bioengineered Labeling Program.

Country of Origin Labeling (COOL) is exactly what it sounds like. It’s the office that oversees federal requirements that consumers know where their food comes from. (As of January 2016, meat companies don’t actually have to disclose the country of origin for pork and beef.) And the Bioengineered Labeling Program is the entity that oversees the enforcement of GMO labeling laws.

COOL, GIPSA, and GMO labeling have one thing in common: They’ve stirred up a lot of controversy in recent years. And the fault lines in debates about the three are similar—small producers based in the U.S. are typically in favor of COOL, advocate for greater GIPSA enforcement, and want GMO labeling to happen. Big meatpackers have lobbied against both COOL and GIPSA.

Housing all three programs under one lower-profile roof could indicate the administration wants to bury them deep within the bowels of the giant bureaucracy that is USDA. It could also mean the administration is simply streamlining the labeling offices. It’s hard to say, since the changes haven’t even been made yet. But it’s the job of advocacy groups to worry about changes at USDA, and worrying is exactly what they’re doing.

“AMS would not adequately enforce market safeguards that would protect family farmers against abusive corporate practices by the very industry that seems to be controlling AMS,” writes The Organization for Competitive Markets, a group that advocates against industry consolidation in agriculture, in a statement. “We are stunned that Secretary Perdue continues to erode farmers’ and ranchers’ anti-monopoly protections, as this action further weakens the marketplace safeguards we need to compete.”

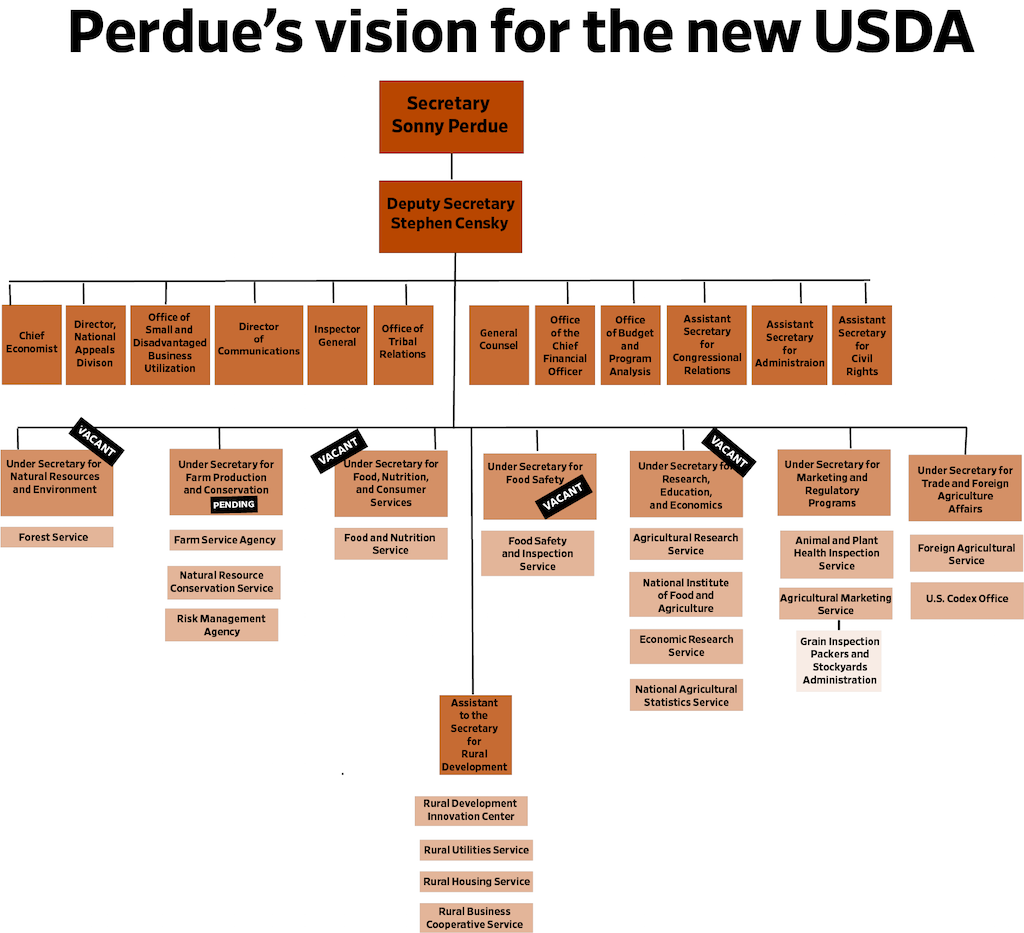

There’s another change that may prove significant: Perdue has sought to eliminate the “rural development” mission area, replacing the Under Secretary for Rural Development with an Assistant to the Secretary for Rural Development. It might seem like semantics, but the shift would mean USDA no longer needs the Senate’s approval to fill the position.

At the same time, the memo calls for “consolidation” of the offices that provide things like housing and utilities services to farmers in rural areas. Perdue has insisted that the change in status actually means the administration is further prioritizing rural development, but NSAC’s Wolfe called the change a demotion. The concrete effects of the move are not yet apparent, but this week’s memo also established a Rural Development Innovation Center under the new category.

Meanwhile, nearly a year into the new administration, four of USDA’s seven under secretary positions are still vacant. If the USDA continues its hiring freeze, this restructure may prove to be less significant than the overall staff shortage. This administration has said over and over again that it’s hoping to deregulate much of the government. Bending the entire apparatus until it breaks would be one way to get there.

Does the Trump administration in all honesty appear to be looking after the “little man?” I personally would say the Trump administration, as with basically all administrations, is looking out for the “big man,” and leaving the “little man” completely out of the equation. Should I see this as surprising, not really, politicians are well known for saying whatever is necessary to gain the voting public’s trust.