Letter from Langdon: Corporate Road Hogs

Letter from Langdon: Corporate Road Hogs

08/18/2014

Missouri’s “right-to-farm” constitutional amendment squeaked by after Big Ag pulled out all the stops in support of the measure. Something stinks, and it isn’t the farm down the road.

Photo by four4dots Meeting in the middle still requires at least one party to yield.

Driving down the middle of the road is a common practice in rural areas, where back roads are marked mostly by two bare tracks. Meeting requires that passing cars yield by splitting the track.

I remember once a long time ago when passing neighbors crunched bumpers on a gravel road. The law was called to establish liability for the crash. When a deputy arrived, he surveyed the scene. Determined no one was hurt. No blows were struck.

That was that.

As he got back into his prowl car he told the drivers: “There is no center line on a country road. Figure it out for yourselves.”

And back to town he went.

When it comes to country roads, farming or neighbors, it’s always better if everyone gives a little. And really, that’s the way it is most of the time. But big-boy politics combined with corporate money always seem to want their half from the middle and both sides.

Right-to-farm amendments are all the craze these days in conservative farm states as Big Ag hogs the road. That’s what happened during the Missouri August primary when Amendment 1 was decided by about 25% of registered state voters. Proponents called it things like “a big thumbs up for agriculture” or “another tool in the toolbox of agriculture.”

Amendment One backers told the world that agriculture in Missouri is under attack by animal welfare groups, nuisance lawsuits where manure spills and odors are courtroom fodder, and environmentalists led by the EPA who want to turn Missouri into a parking lot for environmental laws and regulations that make food and energy production impossible.

When detractors said the right-to-farm amendment looked more like the “China’s-right-to-farm-in-Missouri amendment,” we were told it was nothing like that, even though our state Legislature had done special favors for Chinese owned Smithfield Foods by altering state laws to reduce nuisance lawsuit penalties, and increasing statutory limitations on foreign ownership of Missouri land.

Like a greased pig at a Fourth of July picnic, it was nearly impossible to catch legislators at their game, because most voters never even heard about the change in foreign ownership of land until the controversy erupted.

For something that supporters said was just a modest change in agriculture policy, the politics sure seemed high-stakes. Ninety percent of farm groups with large corporate affiliations and many of those corporations themselves (close to 40 in all) endorsed the amendment. Then all the Missouri members of Congress endorsed it. Even the Democrats. And the Democratic state attorney general did too.

With that much political support, I figured it had to be bad.

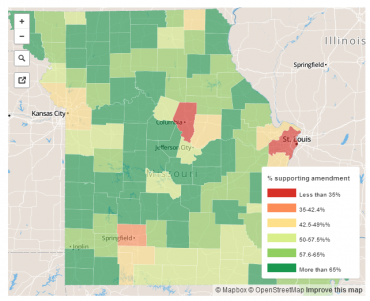

Source: St. Louis Post Dispatch A St. Louis Post-Dispatch analysis showed that support for Amendment One was weakest in urban areas. Only Governor Jay Nixon held back, saying he leaned away from it. Then he moved Amendment One and other issues from the November general election to the August primary, which has a lighter turnout.

We’re still trying to figure out if that hurt or helped. But city turnouts are higher in general elections, and city voters tend to vote “no” on issues like these.

But the real corker was when Mayor Francis Slay of St. Louis endorsed Amendment One, saying he just wanted to extend a hand of friendship to farmers. I know it has nothing to do with it, but coincidentally Mayor Slay’s administration has been trying to establish a trade hub in St Louis … with China.

When Amendment One was placed on the ballot by our General Assembly, polls showed 70% of voters in favor. But when a few small groups representing everyone from family farmers to environmentalists, and yes, even animal lovers, began opposing it, the 70% margin began to shrink.

By the time word got out to voters that, depending on how courts interpreted the vaguely written Amendment One, local control, family farms, our precious natural resources like water, air and soil, and even our own supply of healthy locally grown food could be placed in jeopardy by runaway foreign-owned industrial agribusiness.

It’s a corporate lawyers dream.

Secretary of State Jason Kander has yet to certify election results because Amendment One passed by a narrow 2,500 vote margin. Of nearly 1 million votes cast, one-eighth of registered voters in Missouri Approved One for all of us by a margin of three tenths of one percent.

Now, because of that tight margin, Secretary Kander has ordered state voting precincts to count provisional ballots that are usually discarded uncounted following decisive electoral victories. No one knows how many of those there are, but it is conceivable they could overturn the election in favor of no. Even if they don’t, unless the margin of victory improves above 0.5%, state law says a recount can be called.

Still, that’s a far cry from the 40% margin of victory Big Ag predicted at the start.

Like a friend of mine says, close only counts in horseshoes.

But sometimes moral victories can be scored the same way.

Livestock has an odor to it. I grew up with those smells, as well as with tractor exhaust, dust and noise. There were no enclosed farm tractors then. Everyone sat in the open next to a roaring engine. Way back when, on hot summer days as the corn was laid by, it wasn’t unusual to hear the sound of radio farm-market reports float in on warm summer air from a mile or two away. That’s because farmers turned tractor radio volumes up as high as they could just to hear them over the engine.

Dad’s standard comment from the front porch was always, “Hell, I can probably hear that radio better than Skeeter can.”

Chances are today, if Skeeter played his radio on the edge of town, someone would complain. And if the hog lot took on that special odor it always got after a rain, someone would complain about that too. No one liked that smell, least of all the farmer and his family who lived next to it.

But it’s what we do.

And when a group of farmers including my family built the packing plant five miles west of town, it smelled too. People complained. But the farmers who invested life savings in a successful venture said it smelled like money to them. They did it all without special constitutional perks, because then as now, we had the right to farm without them.

And rural communities prospered.

The biggest difference is that back then all of us, including politicians, had a sense of accountability. You had to look your neighbors in the eye even when you didn’t agree, and there always came the time when fate and the law of averages balanced the scales.

And we never hogged the road.

Richard Oswald, a fifth generation farmer, lives in Langdon, Missouri, and is president of the Missouri Farmers Union.