Farms face steep slide: Net profits this year expected to be half of what they were in 2013

By Cole Epley / World-Herald staff writer Feb 12, 2017

Chad Korth was extracting himself from underneath his pickup late Tuesday morning at the same time the U.S. Department of Agriculture was preparing to issue its lowest forecast for net farm income in 15 years.

The timing was coincidental, but the implications of the lifelong farmer and rancher scoping out the spare tire on his truck foreshadowed the USDA’s grim expectations for farm profitability this year.

“I wanted to see if I could use it and not have to buy another one,” Korth said.

Cost-cutting has become a crucial chore on the family farming operation west of Norfolk near Meadow Grove, where Korth and his 76-year-old father raise several hundred head of cattle and manage about 1,500 acres of pasture and row crops.

The Korths have saved money that would otherwise be spent on fuel by avoiding spraying herbicide in some places and moving more acres into no-till production in others, for example.

“Hopefully we’ll break even” in 2017, said Korth, whose precarious position is mitigated by his wife’s banking job, which helps shore up family finances during tough times on the farm. “It seems like every year you borrow a little more and then borrow some more, and I guess it’s no different than gambling.”

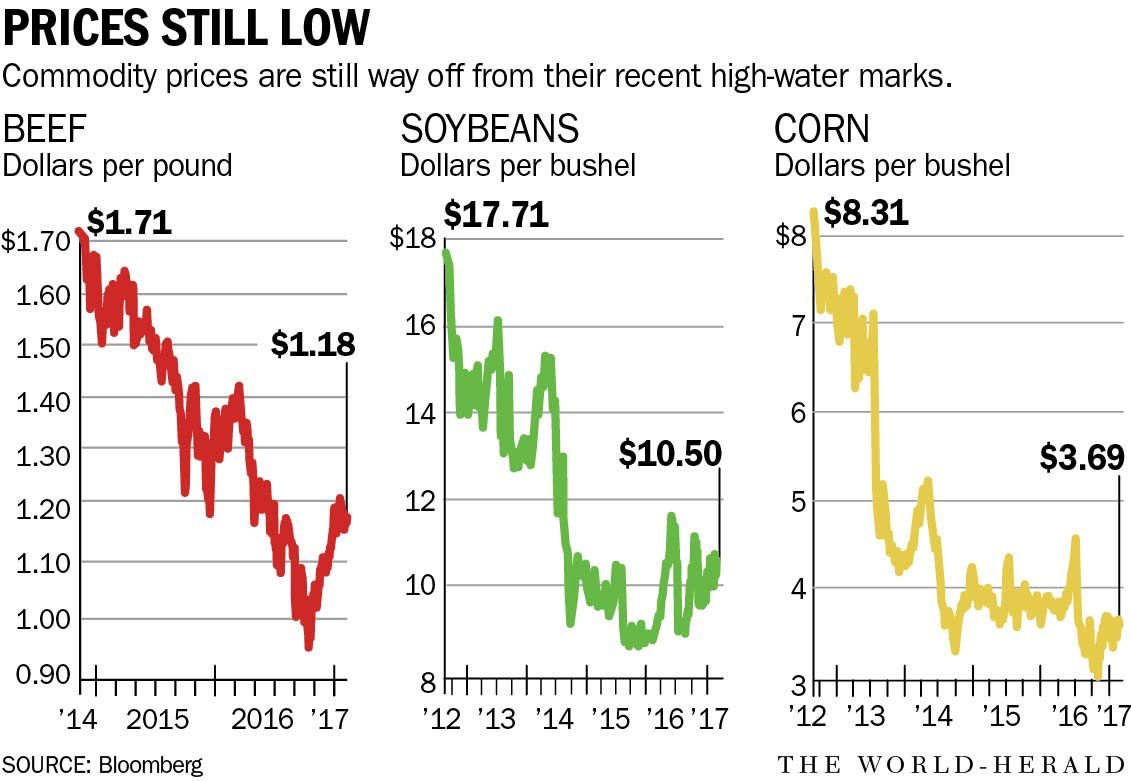

This year, U.S. farmers are expected to net profits of $62.3 billion, or one-half of the record $123 billion they reaped in 2013, according to last week’s USDA report. For many producers facing a fourth consecutive year of declines amid persistently depressed commodities prices, breaking even is a best-case scenario in 2017.

For Jeff Metz, who raises cattle and grows wheat on 5,000 acres of land near the Panhandle community of Bridgeport, the outlook is bordering on untenable.

Like the Korths in northeast Nebraska, Metz also has endured cratered cattle prices that today ring up at only half of last year’s levels. Selling calves for $800 a head after they brought up to $2,000 in recent years only magnifies input costs for expenses like property taxes and feed, Metz said.

Then there’s the wheat business.

The government forecast for wheat prices pegged a year-over-year decline of $1.4 billion, or 17 percent. Record harvests around the world have led to a global glut, and that in combination with a stronger dollar has crumbled the export market to decades-low levels.

“We knew going in to last year’s harvest in July that it was going to be rough,” Metz said. “When you put in for fuel, time, labor and property taxes, our break-even is over $4 a bushel.”

Farmers delivering wheat to rural elevators in western Nebraska last week were barely getting $3.

Metz has farmed his entire life and says he’s still hopeful that prices will rebound in time to bring in enough money to cover the costs of production in 2017. But talk to any farmer long enough and the flame of eternal optimism dims.

“We’re losing a dollar for every bushel that we produce,” Metz said, “and it isn’t going to take long before I’ve got a wheat farm for sale.”

Such financial stresses remain evident in regional banking data recently assessed by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Nathan Kauffman is the Kansas City Fed’s Omaha branch executive and sees growing apprehension from both lenders and borrowers when it comes to taking on additional debt. Last year a “relatively small” group of borrowers were facing real financial problems, Kauffman said, and the odds are increasingly in favor of that group growing.

That could be why demand for new loans suddenly dropped in the fourth quarter.

Among banks in the Fed’s 10th district, which includes Nebraska, new originations of non-real estate farm loans fell off by 40 percent in the fourth quarter, according to a report Kauffman wrote late last month. It’s been almost 20 years since bankers recorded such a decline, and the precipitous drop capped a year in which bankers reported historic or near-historic demand for operating loans.

Kauffman theorizes that many borrowers and lenders finally have sated their appetites for risk and debt as they buckle up for another year of low commodities prices.

“This is still not something that would seem to suggest this is some sort of near-term crisis,” Kauffman said.

But the data suggests there is need for caution.

Repayment rates bottomed out at a level not seen since 1999, which means farmers haven’t been this slow in paying back their loans in almost 20 years.

At the end of the third quarter, 1.7 percent of farm loans were classified as nonperforming. That’s up from 1.1 percent a year earlier and is the highest level since 2012.

Banks’ returns are still good, however, which suggests that performance is not suffering from a relatively higher volume of stressed farm loans. Still, those returns may be boosted by decisions to restructure loans to push out maturity dates, a move that can help borrowers patch over cash shortages in the short term while helping banks avoid past-due payments.

Lenders offer that things aren’t as bad as they could be.

Brad Bauer is senior vice president of Pinnacle Bank’s Nebraska locations and says Pinnacle borrowers with row crops actually exceeded expectations in 2016, thanks mostly to record-breaking harvests for corn and soybeans. Some of it also has to do with paying closer attention to expenses and continuing to make their farms more efficient.

Those in the cattle business were not so fortunate, however.

“Losses were staggering and their profits were nonexistent. With where the market is today, they were able to break even at best,” Bauer said.

“Cow-calf operations” where ranchers maintain a permanent herd of cattle “will certainly have to make some operational decisions” about how best to stay in business at a time when prices are fetching less than half of what they were a year ago, Bauer said.

That doesn’t mean the bank’s standards for approving loans have gotten more strict, but Pinnacle’s loan officers are scrutinizing balance sheets and farmers’ projected cash flows more closely than they have in recent years.

Such is the case at Omaha-based Farm Credit Service of America, a member-owned farm lending cooperative that holds about $25 billion worth of loans for farmers in Nebraska, Iowa, South Dakota and Wyoming.

Farm Credit decided late last year to dispatch at least one full-time employee to each of the lender’s 16 geographic regions to help loan officers and farmers talk through difficulties specific to individual operations and come up with possible courses of action. It also beefed up its Omaha credit underwriting staff with extra number-crunchers to be sure borrowers can, in fact, keep their heads above water in what promises to be yet another year of low commodities prices.

Mark Jensen, the organization’s chief risk officer, said many of Farm Credit’s customers today are struggling to generate adequate cash flow to meet the demands of farming at a low point in the commodities cycle. That’s especially true for crop and livestock producers who had a lot of debt before prices tanked.

On the flip side are those who had little debt heading into the downturn, and falling costs for expenses such as cash rent, fertilizer and seed has brightened the prospect of those farmers’ breaking even this year.

“When you’re in our current environment, coming close to break-even is a win relative to what we have seen the last few years,” Jensen said, noting that the cooperative is seeing more producers getting nearer that point than in recent years.

Bankers are quick to point out that farmers still are but a few years removed from record-breaking profits, and some of those cushions still have some padding left.

With the boom in prices from 2012 still echoing, Myles Ramsey said he hustled to the bank to pay down “almost all” the debt on his 2,600-acre farm near Kenesaw, in south-central Nebraska.

Ramsey farms with his son, Tyler, and now that the pendulum has swung the other way, his operation “definitely lost money in 2016,” he said.

Today his bins are nearly full with last year’s harvest, and they will remain that way until the markets present a price he finds agreeable.

“I can hang in there personally,” he said. “You try to limit your losses in a year like this.”

To be sure, others are wearing thin, however, and some are completely worn through: Farm Credit recently foreclosed on a 1,700-acre row crop operation in Hayes County, in the southwestern corner of the state.

Such an action is a rarity, according to Jensen and land brokers familiar with the area, but the longer profit margins stay tight or even negative, the more drastic decisions will have to be made on farms. That includes downsizing, or even exiting production agriculture completely, Jensen said.

Borrowers in business with First National Bank of Omaha, which has about $1.5 billion in farm loans and is perennially neck-and-neck with cross-town competitor Pinnacle in terms of such loans, already have dialed back, says Tom Jensen, the bank’s senior vice president of ag lending.

“We have had a number of customers that had to do some scaling back … or they will try to feed someone else’s cattle this year,” Jensen said. “The capital and liquidity of the cattle industry has been hit severely.”

Jensen’s perspective is colored by the bank’s heavier concentration of loans to cattle producers, and since it takes significantly more time to gestate and raise a calf than it does for a grain producer to get seed in the ground and take a crop out, market swings in the beef markets are even more difficult to stomach.

Accordingly, First National has tempered its outlook in terms of what it expects to see for farm loan demand in 2017. For those that stay, the odds are good for many that they are due for drastic changes.

“After the (farm crisis in the) ’80s, we thought we would have more weekend farmers and see more of them carrying jobs during the week,” First National’s Jensen said. “I think there will be more of that.”

cole.epley@owh.com, 402-444-1534