Alabama.com: Wastewater spill wipes out 175,000 fish north of Birmingham

posted Jun 14, 2019 | by Dennis Pillion | dpillion@al.com

A major wastewater spill along the Mulberry Fork of the Black Warrior River killed an estimated 175,000 fish and has left residents from Hanceville to Jasper upset about the condition of their river.

According to the Alabama Department of Environmental Management, the event involved the release of partially treated wastewater from a chicken processing plant owned by agricultural giant Tyson Farms Inc.

“I guess it killed the small fish first because those were the first ones that we saw,” said Kim Wright of Empire, who lives on the river more than 20 miles away from the plant. “Then later came the bigger fish, which were gar, striped bass, tons of bass, bass that we would love to catch, huge things.

“All you could smell was dead, rotting fish.”

State officials with the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources released a conservative estimate that 175,000 were killed. But Damon Abernathy, assistant chief of fisheries for ADCNR, said the incident was so large that “direct counts of dead fish were not possible.”

“It appears that most of the fish in the affected area were killed,” Abernathy said. “Dissolved oxygen dropped to levels that most fish cannot easily survive.”

The spill was first reported to ADEM on June 6, “reportedly due to the failure of an above-ground hose/pipe that was being used to pump the partially treated wastewater from one holding pond to another holding pond,” said ADEM’s report.

Residents reported waves of dead fish, including large, hearty species such as catfish and gar washing up in droves and creating an almost unbearable smell.

ADEM said the department had documented low levels of dissolved oxygen up to 22 miles downstream of the Hanceville plant, and noted that dead fish were reported as far as 40 miles from the River Valley Ingredients facility owned by Tyson.

Tyson Farms issued a statement Thursday. “[W]e deeply regret the incident and appreciate the coordination of efforts and help we received from the Alabama Department of Environmental Management and Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources,” the statement read. “We will be seeking guidance from both agencies on our longer-term remediation efforts and will communicate those to the community once we’ve decided on the course of action.”

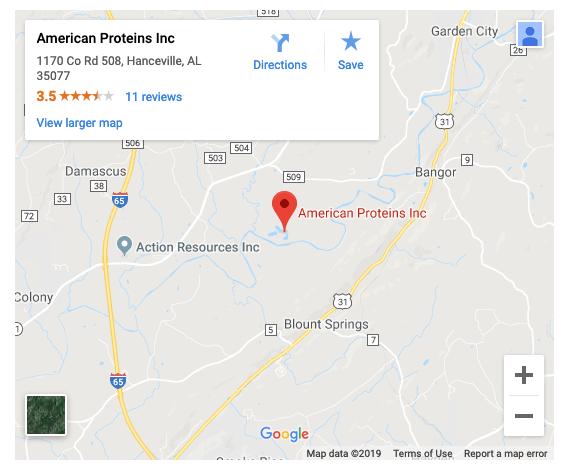

River Valley Ingredients processes the parts of chickens people don’t usually eat to make protein meal for animal feed. The facility has had issues in the past. In 2016, under previous owner American Proteins, the facility caused a significant fish kill after dumping an estimated 900 gallons of sulfuric acid and stormwater into the river.

According to The Cullman Times, American Proteins was the largest poultry rendering operation in the world and its 600-acre Hanceville plant employed roughly 230 people and can process 36 million pounds of offal per week.

Tyson Farms bought American Proteins in 2018 for a reported $850 million.

The Tyson Farms statement also said that dissolved oxygen levels had returned to normal, and that the Mulberry and Sipsey Fork “are available for recreation.”

Black Warrior Riverkeeper Nelson Brooke said that just because dissolved oxygen levels have gone back up does not mean the river is safe for recreation.

“That’s not how you determine if it’s safe to swim,” Brooke said.

Samples taken by Black Warrior Riverkeeper on Monday showed E coli. bacteria at “nearly double the maximum amount allowed by the state of Alabama in surface waters during the summer recreation season.”

‘Dead fish everywhere’

Wright, who said she and her family use the river on a daily basis, watched the fish kill unfold over several days, including numerous visits from government personnel and emergency response teams, which conducted water sampling and hauled away boatloads of decaying fish.

The workers who removed the fish wore fluorescent yellow hazmat-type suits, she said.

Wright said she first knew something was wrong Sunday afternoon, when she and her family stopped by the boat ramp after a trip to Birmingham. “We got out of our vehicle, we were looking around and just there were just dead fish everywhere floating on top of the water,” Wright said.

When they got to their house, Wright said, they learned the spill had reached them and dead fish were even floating up the Sipsey Fork from where it joins the Mulberry Fork.

Wright said she and her husband and two teenage sons use the river almost every day. They have a boat and frequently enjoy bass fishing, and her sons love to swim in the water.

“We’re river people and everybody else that lives around here is the same way,” said Wright. “We live here because of the river, not because of the town or the movie theater. We don’t even have a movie theater. We don’t have anything in this town, but the river.”

Wright said she had spoken with Tyson Farms by phone.

“I asked him what was spilled into the river that killed all these fish and he said ‘organic matter, organic material,’” Wright said. “And as I said, well what does that mean organic matter, organic material, what does it consist of? And he said, ‘ma’am, I can’t answer that.’”

Wright has been actively posting photos and status updates on social media said that whatever environmental fines Tyson has had to pay in the past haven’t been enough.

“I would like them to be shut down,” she said. “I don’t even think they need to operate near the river if they can’t do better than that, because apparently fining them doesn’t make any difference.”

Black Warrior Riverkeeper said that ADEM and ADCNR need to respond with a significant fine to ensure this kind of mistake does not happen again.

“We think that ADEM needs to really drop the hammer on them and effectively fine them in a way that’s going to deter them from continuing to have poor housekeeping practices at their facility that give way to situations like this,” said Brooke.

Brooke said he would also like to see ADEM force Tyson Farms to conduct a thorough engineering analysis of the facility to identify potential problem areas in advance, and to pay for restoration or conservation projects on the river.

“Clearly,” said Brooke, “they have a facility that is not being properly maintained and operated to have so many spills in a short order of years.”