Lincoln Journal Star: Agriculture 2.0? New center aims to connect crop production with health outcomes

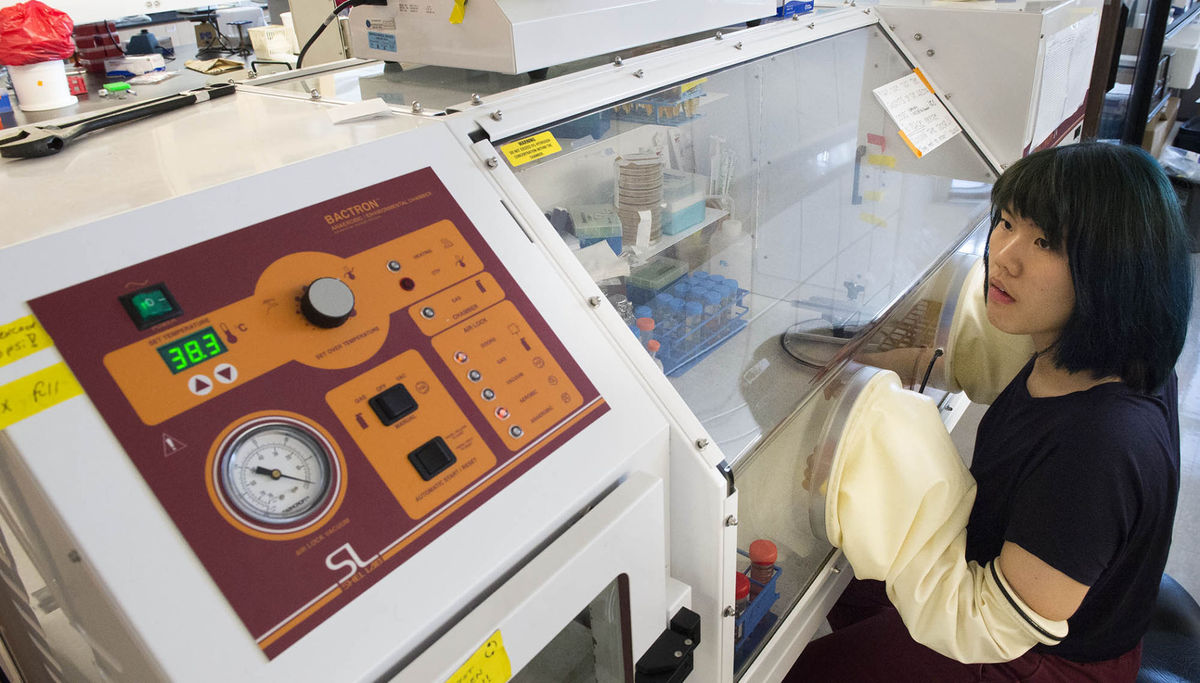

Graduate student Car Reen Kok demonstrates the use of an anaerobic chamber, which mimics the human gut environment through the exclusion of oxygen, in the Gut Biology Lab at Innovation Campus. Gwyneth Roberts | Journal Star

CHRIS DUNKER Lincoln Journal Star | Jul 9, 2017

Jeff Raikes was unapologetic as he shot down pitch after pitch from University of Nebraska scientists aiming to connect research being done on microorganisms in the digestive tract to the broader world.

What the Ashland native and former Microsoft executive sought was an idea he calls “Agriculture 2.0,” connecting Nebraska’s largest economic engine with improving health outcomes in billions of people around the world.

It took time for some of NU’s best minds to catch up, said Robert Hutkins, a food science professor at UNL.

“When we’d come up with an idea we thought was big, Jeff would say to us: ‘Think bigger,’” he said.

The NU researchers eventually did, setting the stage for the Nebraska Food for Health Center, a $40.3 million collaboration among researchers across NU, food and drug manufacturers and philanthropists interested in the intersection between agriculture and medicine.

Andrew Benson, a professor of microbiology at UNL and the initiative’s director, said the university is uniquely positioned to address the challenges the Nebraska Food for Health Center will tackle.

Existing expertise in gut microbiology, plant science, food processing and biomedicine will lead to new discoveries.

“That’s the part that got all of the people involved in this excited,” he said. “The capability of doing something new that nobody had ever done before, that was tremendously innovative and was really something that needed to be done in a place like Nebraska.”

While the NU Board of Regents formally established the center in June, work by scientists to establish a research platform for the initiative stretches back decades.

Benson and Hutkins founded the Gut Function Initiative in 2003, a precursor to the Food for Health Center that partnered food scientists with computer experts, statisticians and nutritionists to explore the relationship between bacteria in the gut and human health.

UNL also created the Gnotobiotic Mouse Facility in 2008 to observe the interaction between dietary fibers and specific gut bacteria in a live animal, said Amanda Ramer-Tait, a co-director.

Stemming from Greek words meaning “known” and “life,” mice in the facility are bred without microorganisms in their bodies, allowing researchers to implant specific bacteria for experiments.

As the next step, Raikes challenged the Gut Function Initiative to connect with other existing centers of excellence around NU, particularly in areas of plant science and production agriculture.

“There are rich sources of commodities that have been exploited for production, agronomic, and yield traits that have not been exploited for health-promoting traits,” Benson said.

Once conversations between specialists in different fields began, it quickly became clear that overlap existed, Hutkins said. Without any administrative call to function, researchers who are now part of the center began to gel.

“It was done under the best of circumstances where researchers with common interests got together, started talking and realizing that we’re all going in the same direction,” he said.

Diverse species of Nebraska-centric crops like corn, beans and sorghum are grown in labs and test fields with the intent of being ground into powder and studied at the molecular level, said James Schnable, an assistant professor of agronomy and horticulture who joined the center.

The powder from the corn plant, for example, is then injected into a test tube, where scientists study how the microorganisms from a human gut interact with it.

If a beneficial outcome is observed — desirable bacteria in the gut get stronger, for example — food scientists like Devin Rose perform screenings to identify the molecule’s properties.

“Once we’ve identified an interesting one, we go in and try to identify what those compounds are that are causing those unique effects,” Rose said.

Schnable said once the molecule is identified, plant geneticists at UNL can then use conventional breeding methods to develop varieties of that particular crop that contain more of the beneficial molecule, potentially creating an added value crop for producers.

Following the test tube experiments, the molecules are tried in a living host — in this case, the microorganism-free animals bred in the Gnotobiotic Mouse Facility.

“It’s a way for us to make sure these changes we see in vitro are reproducible in vivo, so we can add to our understanding on what the impacts are on the host’s physiology,” Ramer-Tait said. “We want to be able to have a beneficial outcome on the host.”

With enough data showing a predictable outcome of a particular dietary molecule, food scientists then find ways to include those beneficial ingredients in food that can be served to human volunteers.

“The lab next to our clinical lab is where they can make cookies and crackers and incorporate the very ingredients we’re interested in into foods,” Hutkins said. “Nobody can do that but us.”

Hutkins recalled the first human study the center conducted using a prebiotic, a nondigestive fiber designed to nourish a beneficial bacteria in the gut to crowd out more undesirable microorganisms.

A private industry partner had found a way to process the prebiotic as a powder that could be sprinkled over cereal or stirred into a glass of milk, but found it was difficult to get the human test subjects to take the right amount.

“We made it into a Tootsie Roll,” Hutkins said. “They had to eat several of these every day and it was so successful that at the end they wanted the leftovers.”

Jacques Izard, who came from Harvard University to join the Food for Health program, is exploring how to engage hundreds of people around the state in a similar clinical trial program.

Participants would be sent kits to collect samples and return them to NU through the mail, he explained.

Benson told regents in June that future human trials could incorporate patients at an upcoming inflammatory bowel disease clinic at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, which could treat as many as 800 patients.

What’s unique about the Nebraska Food for Health Center is the angle from which it approaches its mission, Hutkins said.

“All major universities that have strong medical centers are engaged in gut microbiome health,” he said. “There’s maybe two or three in the United States that come at it from the food science side like we do.”

The center’s novel approach has drawn interest from food and pharmaceutical companies, which see a booming global market for bacteria-nourishing prebiotics, and bacteria-replacing probiotics.

California-based Ritter Pharmaceuticals loaned the center its lead prebiotic for treating lactose intolerance, a compound unavailable anywhere else, according to company founder and President Andrew Ritter.

“This will keep NU at the forefront of prebiotic and microbiome research and ensures the highest quality materials are available for their experience, ultimately strengthening their results,” Ritter said in an email.

Prenexus Health, a prebiotic manufacturer that spun off from a crop research company, partnered with the center after CEO Tim Brummels heard Hutkins speak at an International Food Technology Conference in 2015.

Brummels, a 1984 UNL graduate, said the company plans to sponsor $1 million in research on the prebiotic at NU, which it says is at the forefront of the food supplement industry: combining prebiotics and probiotics into a single product called synbiotics.

“In the seven years we’ve been doing this, the University of Nebraska is leading the way.”

Benson told regents in June that discoveries from the center could “be a goldmine” in the coming years, through patents, technology licenses and companies spun off from the center’s research.

He added epidemics like obesity, as well as chronic conditions like inflammatory bowel disease and lactose intolerance are just the beginning of what “Agriculture 2.0” could address.

To demonstrate the point, he showed regents what a food label of the future could look like.

In place of serving sizes and daily recommended values, the label featured a simple sentence stating that the intake of a particular prebiotic could reduce the risk of active Crohn’s disease by 75 percent.

“This is an audacious goal,” Benson said. “That’s where the center is going.”