China Is Making a Major Play for American Farms and Farmland

China Is Making a Major Play for American Farms and Farmland

Companies backed by the Chinese government are making Big Ag acquisitions in the U.S.

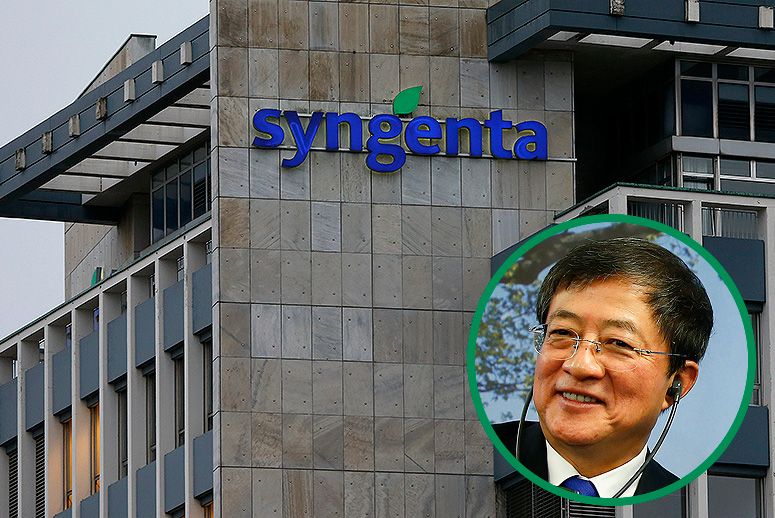

Syngenta headquarters in Basel, Switzerland; Ren Jianxin, chairman of ChemChina. (Photos: Arnd Wiegmann/Reuters)

Feb 22, 2016

Tove Danovich is a journalist based in New York City.

The American farmer is revered in our culture. He—the mythical American farmer is invariably a man—is in many ways a professional embodiment of values, such as individualism and hard work, that are considered part of the national identity. With their backbreaking work, farmers settled the growing West through the 1862 Homestead Act. It’s not a stretch to say that farmers, riding the wave of manifest destiny, built the United States. Today, they continue to feed it.

But the days when anyone could pick up a pitchfork and become a farmer are long gone. Farmland can cost an average of $4,000 per acre in the United States, and most farms have roughly 1,100 acres. Some of the biggest crops, such as corn and alfalfa, aren’t even grown to feed people. Thanks to globalization, food grown in the Midwest might end up feeding someone half a world away.

In an effort to cut out the middleman, foreign buyers are trying to circumvent the American farmer. Instead of buying food from farmers who work their own land, some foreign buyers want to own and operate these American farms themselves—as well as the livestock barns and slaughterhouses. Between the 2013 purchase of pork processor Smithfield by a Chinese holding company and ChemChina’s pending $43 billion offer for the agrichemical company Syngenta, the world’s most populous country is making a major play to buy the proverbial American farm—and U.S. politicians are lending a helping hand.

On Feb. 11, Nebraska’s Republican Gov. Pete Ricketts signed L.B. 176 into law, reversing a 1999 law that prevented meatpackers from owning livestock for more than five days prior to slaughter. Pork processors like Smithfield, which owns a processing plant employing more than 2,000 in Crete, Nebraska, will soon be able to vertically integrate their operations. Instead of buying hogs from numerous independent farmers, farmers will contract with processors like Smithfield for the privilege of selling their pork.

It’s a big concern for farmers who worry the pork industry will be swallowed up by contract farming like the chicken industry. This is one area where pork producers don’t want to be “the other white meat”: Chicken “growers” are paid to raise the birds on their land as well as pay for expensive poultry houses, labor, and maintenance. But it’s the major poultry companies who own the chickens—as well as the hatcheries, slaughterhouses, and feed.

That the Nebraska pork industry is poised for takeover by contract farming isn’t that big of a deal in itself. Most other Midwestern states long ago repealed their own packer bans and have seen pork production climb as Nebraska’s slipped. Nebraska was the last holdout. Though China can benefit from making the state an extension of its food supply, Nebraska legislators are courting China as an important trading partner too. As the executive director of the Nebraska Pork Producers Association noted, the state has the competitive advantage of being the Midwest hog producer closest geographically not just to West Coast markets but to the Pacific Rim as well. But while playing with China could be an economic boon to some in the state, the benefits may not translate to individual farmers—and could damage U.S. agriculture, food security, and the environment as well.

RELATED: Big Poultry Isn’t Just Terrible for Chickens—It Treats Farmers Poorly Too

China is in dire need of both food and farms. While the country looks huge on a map, only 11 percent of Chinese land can be farmed. Add that to the huge population, and you have a recipe for food-security disaster. “Food security, the ability to ensure ample and affordable supplies of food for all, is a political headache for leaders in Beijing, who are all too aware that staying in power means keeping rice bowls filled,” Keith Johnson wrote recently in Foreign Policy.

More than 40 percent of China’s existing arable land has been degraded by pollution, acidification, and reduced fertility, China’s official news agency, Xinhua, reported in 2014. Chinese researchers have estimated a need for a 30 percent increase in rice harvest productivity to feed the population. China’s Number One Central Document, an annual policy blueprint of sorts, has focused on agriculture, rural development, and farmers 13 times since 2000, according to Xinhua.

As a result, China is investing in the best agricultural technology and best farmland—regardless of where it lies—to keep its people fed. The United States, with six times more arable land per capita, is the perfect contract farmer.

“An acquisition like Syngenta by ChemChina really allows them [China] to have this major foothold in feed production as well,” said Ted Genoways, author of The Chain: Farm, Factory, and the Fate of Our Food. “Suddenly you’re looking at the Chinese government being one of the largest players in American agriculture.”

The passage of L.B. 176 was not just a happenstance boon for Smithfield. The company spent $46,222 lobbying Nebraska legislators in the first three quarters of 2015, according to Fortune. Reporter Leah Douglas wrote that in 2015, Smithfield gave more than $12,000 to 19 state senators who were voting on L.B. 176. All but one voted in favor of the bill.

Shaunghui, a private Chinese meat processing company, purchased Smithfield for 30 percent over its market value. Sen. Debbie Stabenow, D-Mich., who was on the committee that reviewed the deal, noted during the hearings, “I firmly believe that economic security is part of our national security and that it should be considered when our government reviews foreign investment into the United States.” Stabenow called the Smithfield purchase “precedent-setting,” as it was the largest-ever purchase of a U.S. company by a Chinese firm. Furthermore, it was the first purchase of a major American food company by a Chinese business.

During the hearing, both lawmakers and the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission presented concerns that the Chinese government was backing the deal. But Smithfield CEO Larry Pope offered assurances that there was no connection between Shaunghui and the Chinese government. The U.S. Treasury Department allowed the purchase to go forward. Yet, just a year later, the Center for Investigative Reporting discovered that the Chinese government did indeed have a connection to Shaunghui. The Communist Party supported the Smithfield purchase with “preferential policy, as well as investment,” Zhang Taixi, the government-appointed president of WH Group (the corporate name Shaunghui adopted in 2014), told CIR.

But the Syngenta deal is not Smithfield 2.0—not exactly. Syngenta is a Swiss company, and in many ways, the merger may not seem all that different from DuPont and Dow’s recently announced coupling. “The big question around Syngenta and ChemChina is that ChemChina isn’t just a Chinese company—it’s a Chinese-government-owned company,” said Roger Johnson, president of the National Farmers Union. This is not the merger of two companies but the second-most-powerful nation in the world seeking to put its might behind one corporation. Johnson added that it was unclear whether China could be expected to behave in an “economically predictable fashion.” In other words, any effect a corporate monopoly might have on an industry could be multiplied to unforeseen levels should the Chinese government decide to interfere with the market—which it has a track record of doing.

Multinational companies that have collaborated with Chinese state-owned enterprises have found themselves in enviable business positions in the past, international strategy consultant Thomas Hout wrote in 2014 in the Harvard Business Review. For example, a U.S. corporation that partners with the government may be able “to develop products in China faster than it otherwise could have,” and those businesses on the other side may find themselves similarly held back.

Based on past behavior, allowing the deal with Syngenta to go through raises the possibility that China could use its new acquisition to gain an unfair advantage over the global seed market, Johnson said. If more seed companies consolidate (or are pushed out of business), the consequences could be dire for the genetic diversity of seeds sold on the commercial market.

Past mergers between seed companies have allowed them to simplify their total catalog of offerings. Focusing on corn, soybeans, and cotton, the USDA’s Economic Research Service found that new research and development stopped or slowed as the seed industry began to consolidate in the 1990s. “Those companies that survived seed industry consolidation appear to be sponsoring less research relative to the size of their individual markets than when more companies were involved,” agricultural economists Jorge Fernandez-Cornejo and David Schimmelpfennig wrote in a 2004 USDA publication. They added, “Fewer companies developing crops and marketing seeds may translate into fewer varieties offered.”

Consolidation of seed varieties is not a new trend. Throughout the history of agriculture, farmers have selected and saved seed varieties that were best adapted to their specific soil and climate conditions, resulting in thousands of variations of the same plant. But the largest seed companies prefer to sell a lot of just a few varieties of seeds to maximize profits. Over time, this one-size-fits-all approach to food has cut down on the types of commercially grown apples, oranges, and many other foods.

Some less popular varieties are lost for good, and seed varieties that were once perfectly adapted for a location may no longer exist. Those who are worried about seed diversity, especially in the face of climate change, worry that the shrinking choice of genetics could have disastrous consequences.

Johnson noted that mergers also reduce competition, causing the prices of seeds to rise. Consolidation was the highest during the 1990s and—after a brief slowdown—continued again into the late aughts, Philip Howard wrote in Sustainability in 2009. Between 2001 and 2010, according to the USDA, the price of genetically engineered corn and soybean seeds rose by 50 percent.

Another possibility is that the Chinese government could fast-track the approval of new genetic traits developed by Syngenta for use in China while allowing those from other countries and companies to languish, Johnson said. The Chinese market is, in some years, an important importer of corn—enough so that U.S. farmers take note of the type of corn China is buying. (In other years its corn production is high enough that it has been the source of the second-largest corn exports.) Those farmers who grow corn for the export market could find themselves shut out of the Chinese market unless they grow approved varieties of corn. If Syngenta owned the only approved corn for import to China, it would give the company an effective monopoly over any farmer who hoped to export to that market.

Though WB Group is technically an independent company, many members of its board of directors were appointed by the Chinese government. The company also received preferential treatment and financial backing when proceeding with the Smithfield deal. As a result, there are unanswered questions about just how much distance there is between a corporation like WB Group and the Chinese government. If China decided to grant preferential treatment to Smithfield imports, it would be a huge economic coup, as China is the world’s largest consumer of pork. Thanks to L.B. 176, the WB Group–owned Smithfield could now take steps to own the entire production chain for pork production with the least geographic distance between U.S. pork production and the Chinese market.

There are those who dislike the intrusion of agribusiness into the U.S. food system and figure that any problems facing conventional farmers or agrichemical companies as a result are a win. But there are environmental and public health factors to consider as well.

One of the benefits to owning every aspect of production from feed through packaging is that “you can increase production essentially at will,” said Genoways. That production will lead to more barns being built and, in turn, waste coming out of those barns. “You need more feed for those pigs, so you’re raising more row crops and putting more of that waste onto the fields,” he explained. “It becomes a feedback loop.”

He pointed out that “this isn’t theoretical,” offering Iowa’s pork industry as an example. In the early 2006, Hormel sued the government, asserting that Iowa’s packer ban—which, like Nebraska’s law, prevented pork processors from owning pork themselves—violated the U.S. Constitution. The company successfully received an injunction preventing the state from enforcing the existing law, allowing Hormel to begin contract farming in Iowa.

Between 2007 and 2012, Iowa had the largest increase in hog and pig sales of any state in the country—a jump of $1.9 billion. The runner-up, Minnesota, saw increases of only $600 million during the same period.

Based on the events in Iowa, Genoways predicts Nebraska will soon experience increases in surface water pollution. The number of polluted Iowan waterways increased 15 percent between 2012 and 2014, according to the state’s Department of Natural Resources. That’s not all. Not only do the waste pits used to capture manure from large hog operations produce antibiotic-resistant bacteria, but new research is beginning to show that the pathogens can travel miles away.

Despite economic, environmental, and public health concerns, it looks like there is little political inclination to stop mergers like Syngenta’s or Smithfield’s from happening.

As Genoways said, “We haven’t just allowed vertical integration to come in; we’ve handed over a vertically integrated system to a foreign government.” All we can do now is wait and see what the consequences will be.